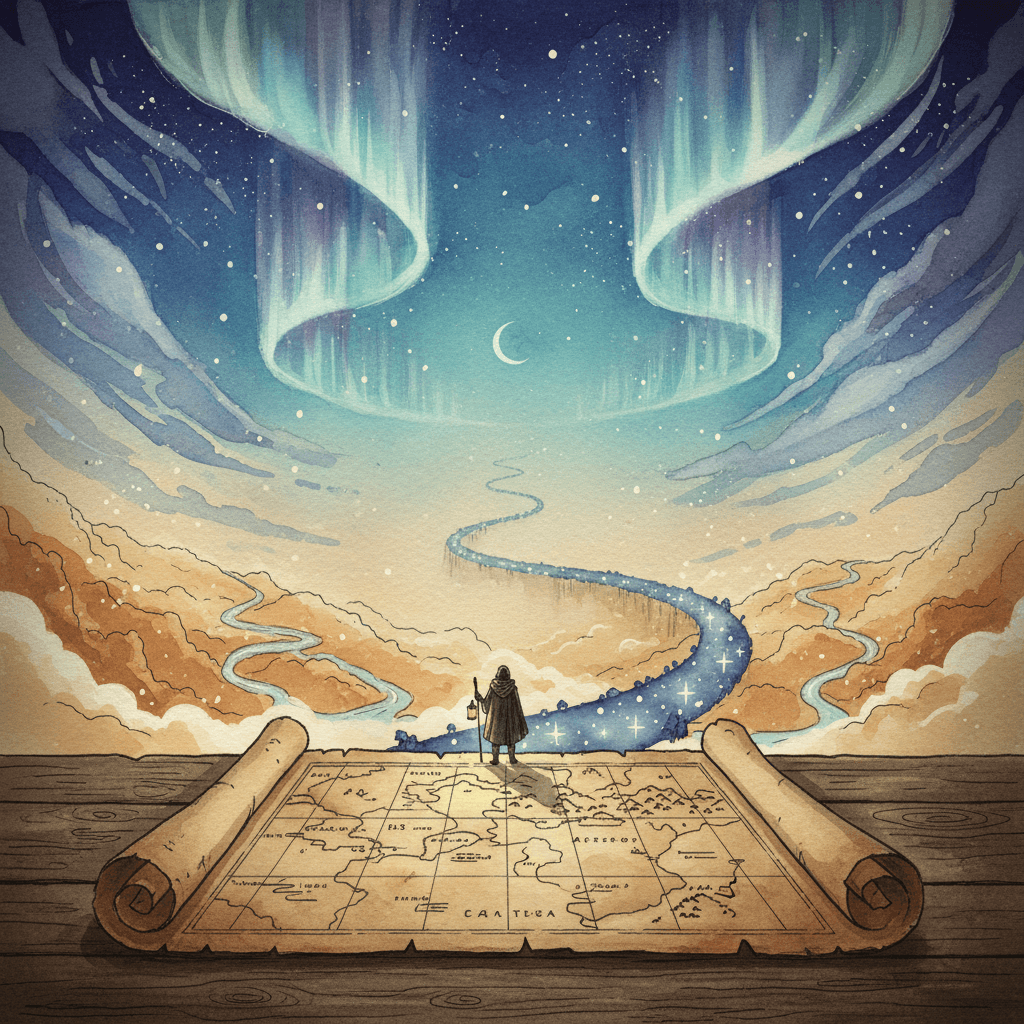

Mapping Awe and Venturing Beyond Its Edges

Create a map of wonder, then travel beyond the edges. — Kahlil Gibran

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Where does this idea show up in your life right now?

The Map and the Invitation

Gibran’s line entwines two impulses: to name what astonishes us and to step past what names can hold. A map of wonder gathers the contours of what moves us—places, questions, encounters—so that we are oriented rather than overwhelmed. Yet, by insisting we then travel beyond the edges, the quote acknowledges a paradox: orientation is preparation, not destination. The moment a chart feels complete, it risks becoming a cage.

Gibran’s Mystic Cartography

This tension runs through Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet (1923), where love, freedom, and work are traced like coastlines, only to dissolve into open sea. “Let there be spaces in your togetherness,” he writes, urging intimacy that does not possess—a gentle crossing beyond the ego’s borders. Influenced by Maronite spirituality, Sufi lyricism, and Nietzschean self-overcoming, Gibran uses poetry as a compass that points outward, suggesting that the truest map is one that keeps us moving.

Awe as a Cognitive Compass

Modern psychology shows why wonder maps are worth making. Studies in Psychological Science by Rudd, Vohs, and Aaker (2012) found that awe expands perceived time, increasing patience and presence—mental space in which to chart what matters. Building on this, Piff et al. (JPSP, 2015) reported that awe softens the self-focus, nudging people toward generosity and curiosity. As Dacher Keltner’s Awe (2023) synthesizes, awe shrinks the “small self” while enlarging our sense of possibility, priming us to approach edges with humility rather than fear.

Edges in the History of Maps

Cartographers have long confessed the limits of their diagrams. The Hunt–Lenox Globe (c. 1510) notoriously hints at “Hic sunt dracones”—here be dragons—where knowledge frays. Likewise, Borges’s “On Exactitude in Science” (1946) satirizes the fantasy of a perfect map, reminding us that fidelity without function is folly. By contrast, Marshallese stick charts encoded swells and currents rather than coastlines, proving that good maps can guide without pretending to be the world. Each example whispers Gibran’s counsel: use the chart, then face the waters it cannot picture.

Art That Crosses the Margin

Artists often stand at the edge and listen. Keats’s notion of “negative capability” (letter, 1817) celebrates dwelling in uncertainties without reflexive grasping, a poise crucial for stepping beyond mapped certainties. His sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” (1816) likens discovery to a stunned conquistador—misnamed as Cortez—peering at an unrealized ocean. In a complementary key, Blake’s aphorism in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790–93) suggests that cleansed perception reveals the infinite. The arts, then, do not merely draw the map; they attune us to the shimmer beyond its frame.

Science at the Rim of Paradigms

Scientific revolutions begin where the legend fades. Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) argues that anomalies accumulate at the map’s margins until a new chart is required. Einstein’s 1905 paper “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies” stepped past Newtonian coordinates to redraw space and time. Likewise, Wegener’s continental drift (1912), mocked for decades, seeded plate tectonics in the 1960s. In each case, careful mapping of puzzles made the leap possible, yet the breakthrough came only by traveling past the accepted borders.

Practices for Traveling Past the Edge

Practically, begin by sketching a personal “wonder map”: cluster the questions, places, and people that ignite awe. Then, in Gibran’s spirit, schedule edge-trips—experiences likely to disconfirm your assumptions. Stuart Kauffman’s “adjacent possible” (At Home in the Universe, 1995) suggests that novelty hides just one step past the known; design prompts like Hal Gregersen’s question bursts (Questions Are the Answer, 2018) help you locate that step. The map becomes a living invitation: orient, venture, revise, repeat—until the edge moves, and with it, you.