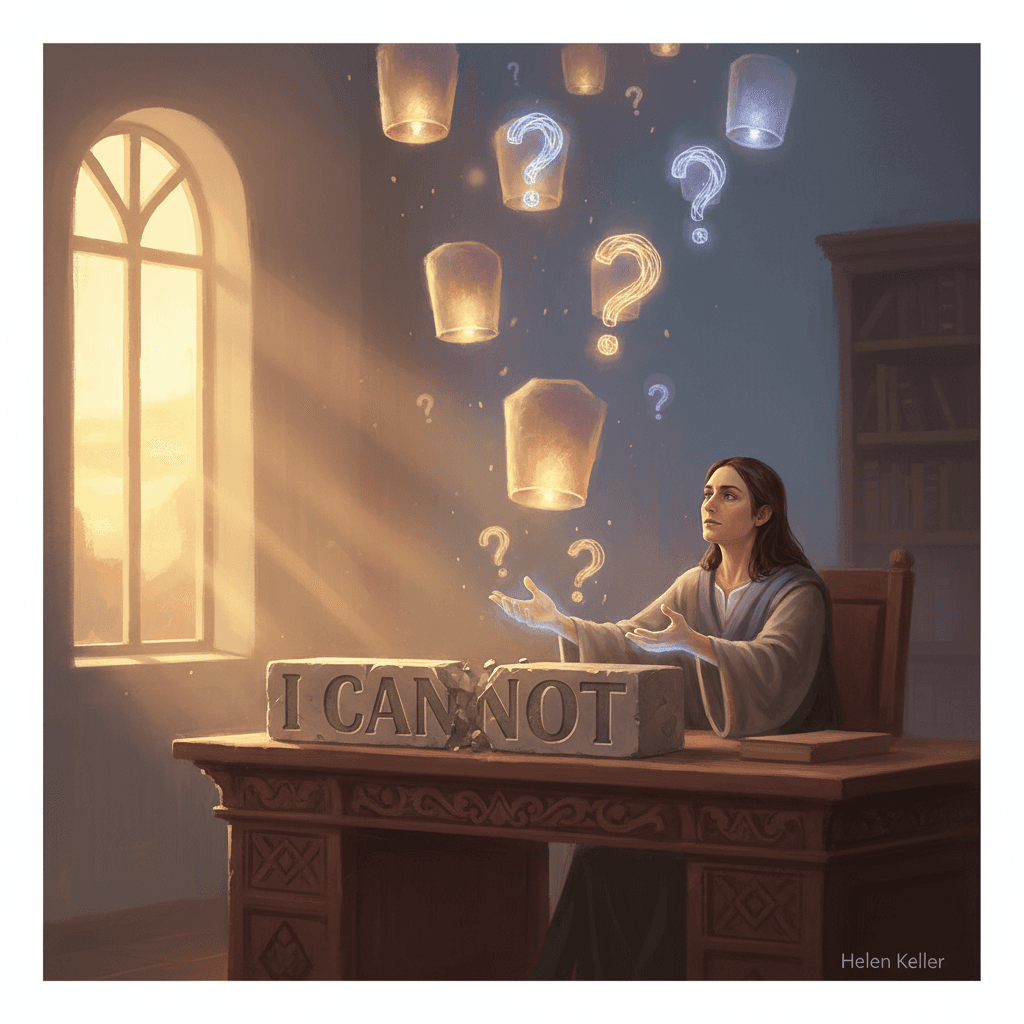

Transforming Every Limitation Into Living Questions

Turn every 'I cannot' into a question worth answering. — Helen Keller

Reframing the Language of Limitation

Helen Keller’s directive to “turn every ‘I cannot’ into a question worth answering” begins by challenging the way we speak to ourselves. The phrase “I cannot” closes a door; it presents ability as fixed and possibilities as already judged and denied. By contrast, a question inherently invites curiosity and exploration. Thus, Keller suggests that the first step in overcoming limits is not physical action but linguistic transformation—shifting from statements that end discussion to questions that open new paths.

From Defeat to Inquiry

Once we recognize the finality in “I cannot,” the next move is to convert it into a productive inquiry: “How could this be possible?” or “What would it take to learn this?” This subtle turn reorients the mind from defeat toward problem-solving. Instead of accepting incapacity as a verdict, the question frames it as a challenge. Much like Socrates in Plato’s *Apology* (c. 399 BC), who uses questions to expose hidden assumptions, Keller’s advice urges us to interrogate the reasons behind our limits rather than surrender to them.

Curiosity as an Engine of Growth

Transforming “I cannot” into a question also elevates curiosity from a casual interest to a driving force. A well-posed question—“What skill am I missing?” or “Who could help me do this?”—creates a roadmap for growth. Educational research consistently shows that inquiry-based learning fosters deeper understanding because questions activate intrinsic motivation. In this way, Keller implies that the energy to overcome obstacles does not spring from willpower alone but from the genuine desire to discover what lies beyond our present abilities.

The Power of Questions in Adversity

Keller’s own life embodies this shift from limitation to inquiry. Deafblind from early childhood, she could easily have remained confined by unasked questions. Instead, with Anne Sullivan, she continually turned impossibilities into investigations: How can language be taught through touch? How can a person without sight or hearing attend college? Her achievements, such as graduating from Radcliffe College in 1904, testify that asking difficult questions can carve out new methods where none previously existed. Thus, her quote is not abstract philosophy but a distilled lesson from lived adversity.

Crafting Questions Worth Answering

Not every question sparks transformation; Keller emphasizes those “worth answering.” Such questions are specific, actionable, and oriented toward learning rather than self-judgment. Instead of “Why am I so bad at this?”, a more fruitful reframing is “What is one small step I could take to improve?” This shift avoids shame and focuses on process. Over time, a habit of asking high-quality questions reshapes our internal dialogue: each former barrier becomes a prompt for creativity, collaboration, and experimentation.

Living a Question-Driven Life

Ultimately, turning “I cannot” into a question is an invitation to live more experimentally. Rather than organizing life around the avoidance of perceived weaknesses, we begin to orient it around ongoing inquiry: What else is possible for me? How might I contribute despite my constraints? As Rainer Maria Rilke advised in *Letters to a Young Poet* (1929), we can “live the questions” until answers gradually emerge through action and time. In this continuous cycle of questioning and discovery, Keller’s insight becomes a daily practice of expanding what we believe we can do.