Creating Our Way Beyond Fear’s Persistent Voice

Keep your hands busy with creation, and fear will learn to sit quietly — Langston Hughes

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Where does this idea show up in your life right now?

Turning Hands Into Anchors of Courage

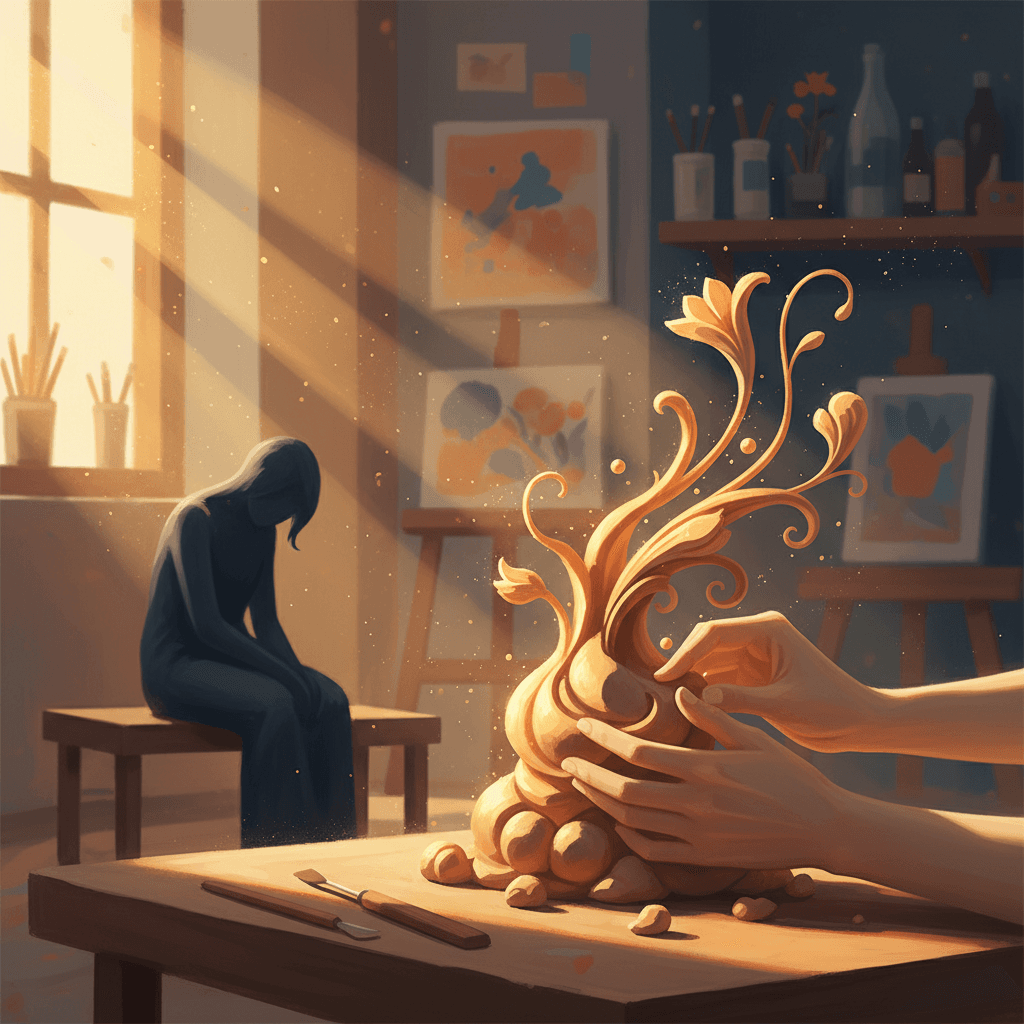

Langston Hughes suggests that what we do with our hands can transform what happens in our minds. By urging us to "keep your hands busy with creation," he reframes courage not as a feeling we must wait for, but as a practice we can enact. Rather than wrestling directly with fear, Hughes invites us to anchor ourselves in making—writing, building, cooking, sewing, drawing—so that courage arises indirectly, as a quiet companion to focused work.

Creation as a Gentle Antidote to Anxiety

Instead of demanding that fear disappear, Hughes imagines it “learning to sit quietly.” This subtle phrasing acknowledges that fear may never fully vanish; it simply loses its power to dominate. Psychologists now describe a similar dynamic in behavioral activation therapies, where meaningful action interrupts spirals of worry. When we create, our attention shifts from catastrophic possibilities to tangible problems we can actually solve—what color to choose, which word to place, how to shape the next line or stitch.

From Harlem Renaissance Struggle to Personal Agency

Hughes wrote amid the Harlem Renaissance, a period charged with both artistic brilliance and deep social fear. His own life—marked by racism, economic insecurity, and political pressure—shows how creation can be an act of defiance. Poems like “Let America Be America Again” channel collective anxieties into crafted language, transforming paralysis into protest. In this light, his advice is not simply self-help; it is a blueprint for turning private dread into public art and, ultimately, into social change.

The Discipline of Making as Everyday Resistance

Crucially, Hughes highlights busyness with "creation," not mere distraction. Scrolling endlessly or numbing out with entertainment keeps our hands occupied but rarely quiets fear; it simply postpones it. Creative work, by contrast, requires intention and discipline. Whether someone tends a garden, repairs a bicycle, or drafts a short story, each small act of making asserts, "I can shape something in this world." Over time, this steady practice becomes a kind of everyday resistance to helplessness.

Letting Fear Stay, but Not Lead

In the end, Hughes offers a compassionate stance toward fear. Rather than insisting we become fearless, he suggests we let fear take a seat in the corner while we continue to build. This mirrors modern mindfulness teachings that encourage us to notice anxiety but still act in line with our values. When our hands are engaged in creation, fear remains present but no longer commands the room; our work, not our worry, becomes the louder voice.