When Restless Thoughts Demand To Become Reality

Allow your ideas to stretch into action; thoughts ache to become things. — James Baldwin

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

What feeling does this quote bring up for you?

The Restlessness of Untaken Action

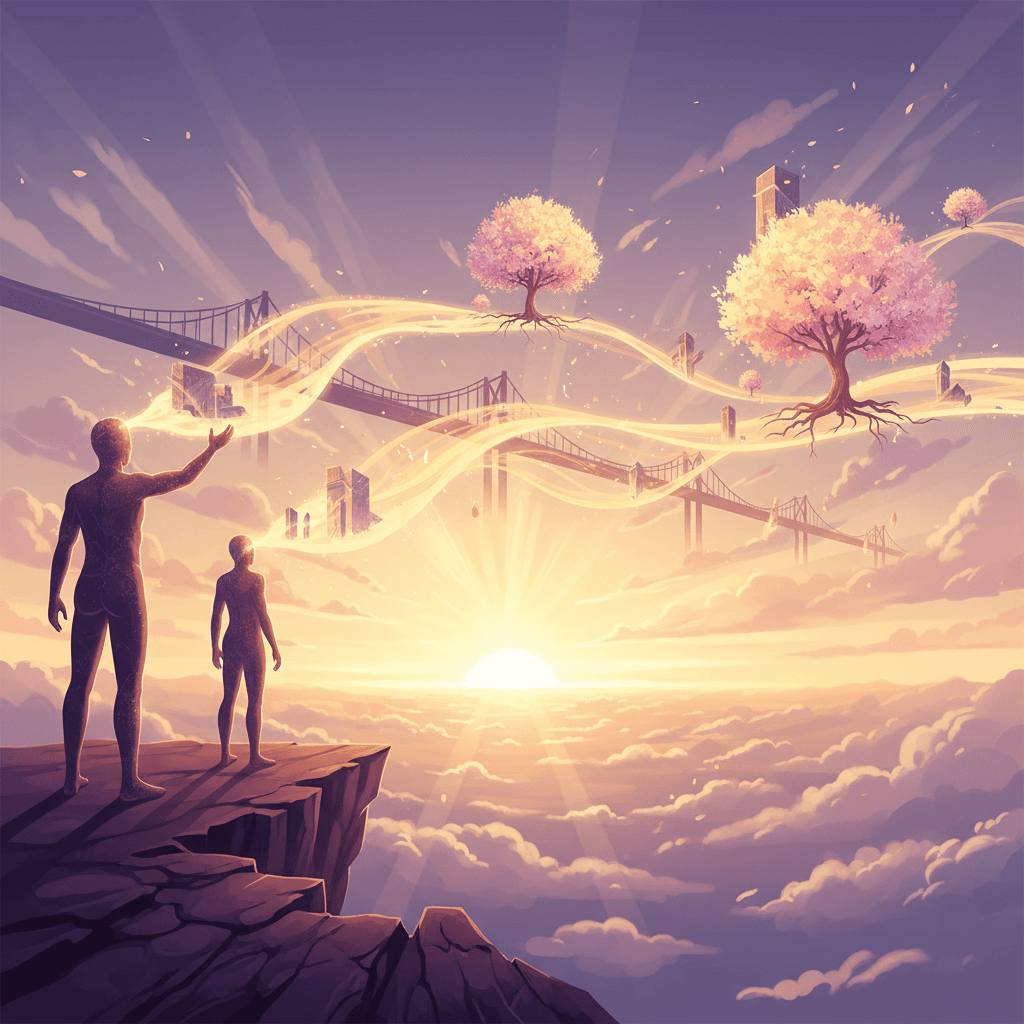

James Baldwin’s line, “Allow your ideas to stretch into action; thoughts ache to become things,” captures the discomfort of potential left unused. Ideas, in his view, are not passive wisps of imagination but living pressures that push against the walls of our inaction. Just as an unused muscle tightens and aches, unexpressed thought generates a subtle pain—an inner tension that reminds us something more is possible. By framing thoughts as aching to become things, Baldwin suggests that imagination carries an inherent responsibility: once we see more clearly, we are no longer innocent in our passivity. The mind, therefore, is not just a private theater but the staging ground for what might enter the world.

From Contemplation to Creative Responsibility

Moving from this inner pressure, Baldwin’s insight reframes thinking itself as a moral and creative duty. It is not enough to indulge in sharp analysis or beautiful visions if they remain sealed off from lived reality. Philosophers from Aristotle to Hannah Arendt have warned that contemplation without praxis can curdle into complacency. Baldwin, rooted in the urgencies of civil rights and artistic truth-telling, intensifies this warning: once an idea has formed, it carries a claim on us. The more clearly we understand injustice, beauty, or possibility, the less defensible it becomes to stand still. Thus, the act of thinking becomes a kind of promise that demands fulfillment in the world outside our heads.

The Ache of Unlived Possibilities

This is why Baldwin speaks of an ache rather than a simple desire: the pain comes from dissonance between who we are and what we know we could do. Psychologists describe a similar tension as “cognitive dissonance,” the stress felt when beliefs and actions don’t align. A person convinced of the need for change but frozen in fear experiences a quiet torment, like a door rattling on its hinges but never opening. Baldwin names that rattle: ideas straining toward embodiment. The longer the gap between vision and movement, the sharper the ache becomes. In this sense, our discomfort is not an enemy; it is a signal that our inner world has outgrown the confines of our current behavior and is pressing us toward growth.

When Thought Becomes Tangible Change

Yet Baldwin does more than diagnose this tension; he invites a concrete response. Allowing ideas to “stretch into action” implies a gradual, sometimes awkward extension from intention to deed. Social movements offer vivid examples: the U.S. civil rights struggle began as a constellation of convictions about dignity and equality, then expanded into boycotts, sit-ins, and legislation. The Montgomery bus boycott of 1955–56, for instance, transformed a shared idea—refusal to accept humiliation—into sustained collective action that disrupted daily routines and legal norms. Art follows a similar path: a novelist’s vague intuition becomes an outline, then a draft, then a book that alters readers’ perspectives. In both cases, the world is different because a thought refused to remain abstract.

Courage, Imperfection, and the First Small Step

Of course, the journey from idea to reality is rarely clean or heroic; it is stitched from imperfect attempts. Baldwin’s phrasing, “allow your ideas,” hints that the main barrier is often our own reluctance. Fear of failure, ridicule, or unintended consequences can keep even our most urgent insights locked away. Yet history and everyday life show that action typically begins with modest, vulnerable moves: a conversation started, a prototype built, a boundary set, a line of truth written and shared. Each small embodiment lessens the ache by bringing thought and behavior into closer alignment. In doing so, we discover that ideas do not merely become things; they also remake us, turning hesitant thinkers into participants in the unfolding shape of the world.