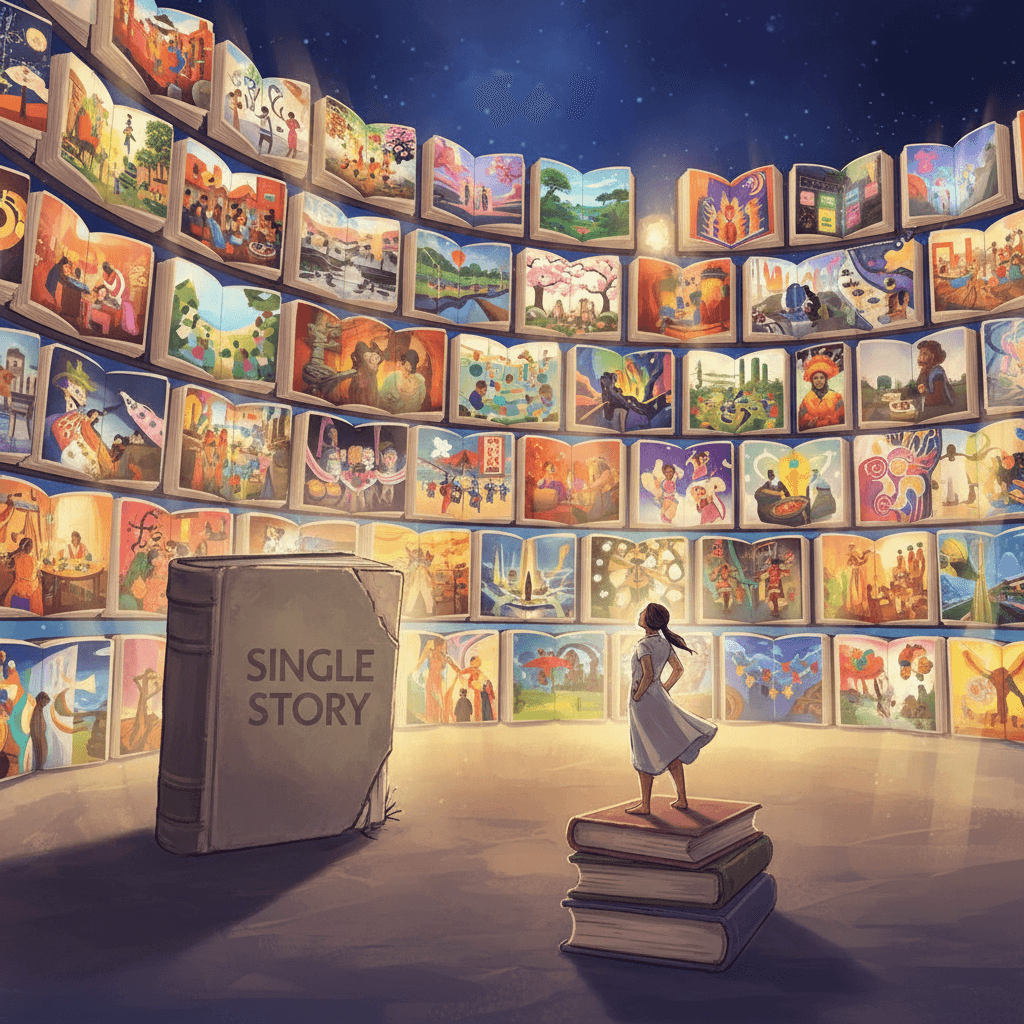

Beyond the Single Story: Rethinking Stereotypes

The problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story. — Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

What's one small action this suggests?

From Falsehood to Incompleteness

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s line reframes how we think about stereotypes. Rather than dismissing them as sheer lies, she argues that their danger lies in being partial truths treated as complete realities. This subtle shift matters: if we assume stereotypes are always untrue, we may feel safe ignoring them; but if we see them as fragments mistaken for the whole, we recognize how easily any of us can participate in them, even with accurate facts, simply by leaving too much out.

The Power and Peril of a Single Story

Adichie expands this idea in her TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story” (2009), where she recalls arriving in the United States and being met with one story about Africa: poverty, war, and helplessness. None of this was entirely fabricated, yet it erased thriving cities, literature, and everyday joy. By turning one narrative into the narrative, stereotypes strip people of their complexity, much as a silhouette captures a recognizable outline but omits depth, color, and motion.

How Stories Become Stereotypes

To understand how incompleteness hardens into stereotype, it helps to see how stories circulate. Media, school curricula, and casual conversations often repeat the same limited examples: a single kind of immigrant, a single kind of teenager, a single kind of rural town. Over time, repetition grants these images an undeserved authority. As with a photo album that preserves only a family’s celebrations and never their disagreements, the selected images start to masquerade as the full truth, shaping expectations before we even meet one another.

Human Consequences of Incomplete Narratives

When one story becomes the only story, it narrows not just our understanding but also people’s possibilities. Adichie describes a college roommate who was astonished that she spoke English so well and listened to Mariah Carey, because the roommate’s single story of Africans left no room for shared cultural touchpoints. Such assumptions subtly influence hiring decisions, school discipline, and healthcare encounters. A teacher who has absorbed a single story about a “quiet” ethnic group may overlook a child’s struggle; a doctor who believes a group is “stoic” may misjudge their pain.

Multiplying Stories to Restore Complexity

If the core problem is incompleteness, the remedy is not silence but more stories. Adichie emphasizes reading widely, listening across class and culture, and telling our own experiences in all their contradiction. When we hear multiple stories about a place—say, both the hardship and creativity in Lagos, or the conservatism and solidarity in a rural town—the stereotype loses its grip. Much like adding new angles to a sculpture, every additional narrative reveals contours we could not see before, inviting us to approach others with curiosity rather than prepackaged certainty.

Practical Ways to Resist the Only Story

Challenging the single story begins in daily habits. We can notice when a description uses “always” or “they all,” and deliberately ask, “What am I not seeing?” Seeking novels, films, and news from the people being described, rather than only about them, widens the frame. In conversations, inviting others to share their background—and being willing to revise our first impressions—helps ensure that no one is reduced to a role. Through these small practices, Adichie’s warning becomes a constructive ethic: to honor the many stories each person carries.