Beyond Ease: Where Character Takes Its Shape

Push past ease; that's where shape and strength form. — Emily Dickinson

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

What does this quote ask you to notice today?

The Call to Move Beyond Comfort

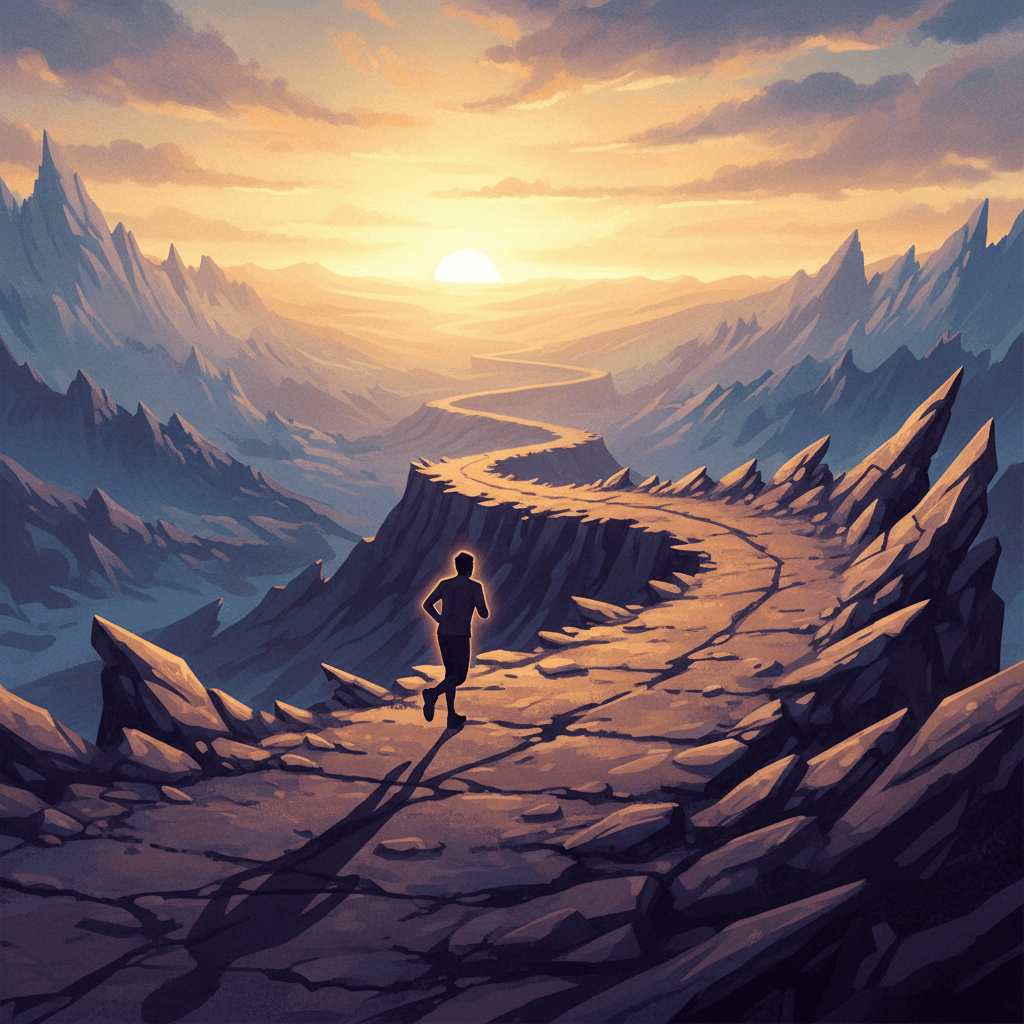

Emily Dickinson’s line, “Push past ease; that's where shape and strength form,” distills a timeless challenge: do not settle for what feels effortless. Rather than praising struggle for its own sake, she points toward the region just beyond comfort, where resistance begins. In this view, ease is not a villain but a starting point, a necessary baseline from which we must eventually step if we want to grow. Thus, the quote frames discomfort not as a misfortune to be avoided, but as a signal that we are entering the territory where real change becomes possible.

How Resistance Shapes Our Inner Form

Continuing from this idea, the words “shape and strength” suggest that who we are is molded by what we are willing to endure. Just as clay must be pressed and fired to become a vessel, character is refined under pressure. Philosophers from the Stoic tradition, such as Epictetus in his *Discourses* (c. 108 AD), argued that adversity reveals a person’s true nature. Dickinson’s phrasing goes a step further, implying that adversity does more than reveal; it actively sculpts. The bumps, doubts, and failures along the way become the contours of our eventual resilience.

The Discipline of Training Against Friction

The metaphor carries naturally into the realm of physical effort, where strength literally depends on resisting ease. In exercise science, muscles grow through progressive overload: lifting slightly more than they can comfortably handle, recovering, and then repeating. A novice runner who lengthens each run just beyond what feels simple experiences this principle firsthand. Dickinson’s insight aligns with this: we do not gain strength by repeating what is already painless, but by flirting with the limits of our current capacity, retreating to rest, and returning a little stronger each time.

Creative Growth in the Uncomfortable Zone

Moreover, the same dynamic appears in artistic and intellectual work. A poet who only uses familiar forms, or a programmer who never learns a new language, may feel efficient yet stagnant. Historically, innovations often emerged when creators leaned into discomfort—consider how James Joyce’s *Ulysses* (1922) broke narrative conventions, initially bewildering readers but ultimately expanding literature’s possibilities. Dickinson herself, with her compressed lines and dashes, stepped outside the poetic ease of her era. Thus, pushing past ease becomes not just a discipline of the body or will, but a catalyst for originality and depth.

Finding the Edge Without Courting Harm

However, moving beyond ease does not mean glorifying burnout or constant struggle. The key is the edge—where tasks feel challenging but still possible. Psychologist Lev Vygotsky’s concept of the “zone of proximal development” (1934) captures this: learning is most efficient where material is just beyond current mastery. Applied to Dickinson’s line, we are invited to seek that zone intentionally, noticing when things are too easy to shape us or so hard they crush us. In this balanced pursuit, discomfort becomes a guide rather than an enemy, marking the frontier where our next version is quietly taking form.

A Daily Practice of Chosen Difficulty

Bringing the idea into everyday life, pushing past ease can be surprisingly modest: initiating the hard conversation instead of postponing it, attempting a difficult chapter instead of rereading notes, or choosing a small but demanding project at work. Over time, these chosen difficulties accumulate into a distinct personal shape—a person known for courage, persistence, or depth. Dickinson’s simple imperative thus becomes a daily practice. Each decision to step just beyond what is comfortable reinforces the message to ourselves: we are still being formed, and we are willing to meet the conditions under which real strength is made.