Planting Tomorrow With the Lessons of Loss

Gather lessons from loss and plant them ahead. — Frederick Douglass

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Where does this idea show up in your life right now?

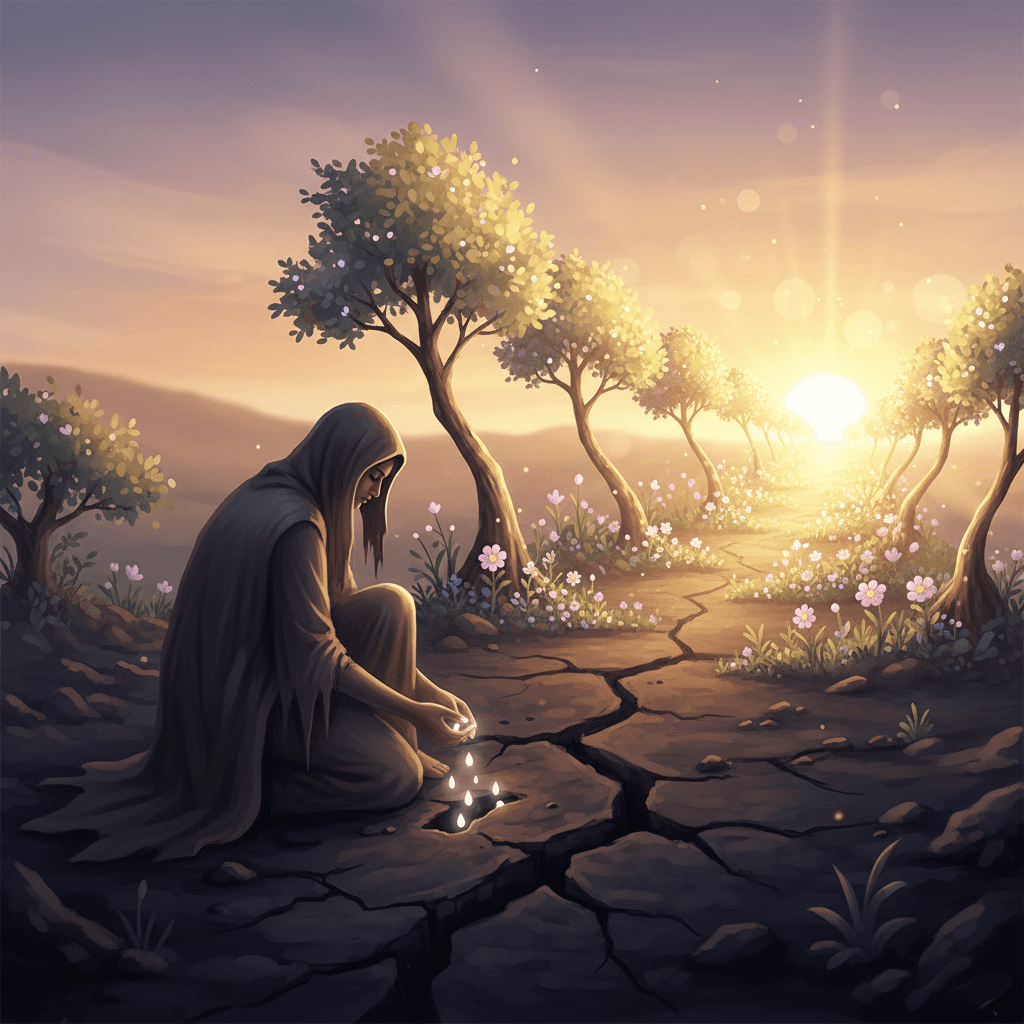

Loss as Fertile Ground, Not Wasteland

Frederick Douglass’s line, “Gather lessons from loss and plant them ahead,” invites a radical re-framing of pain. Instead of treating loss as sterile ground where nothing good can grow, he suggests it can be tilled for insight. Loss may strip away illusions, comforts, or cherished plans, yet in doing so it exposes the soil of our character. By seeing hardship not as a dead end but as a field to be worked, we shift from mere suffering to purposeful reflection. Thus, the first move is inward: to notice what a setback reveals about our values, limits, and strengths, rather than only what it has taken away.

The Active Work of Gathering Lessons

However, Douglass does not say that lessons will fall into our hands automatically; he speaks of gathering them. This implies deliberate effort: questioning our reactions, tracing causes, and naming what we might do differently. After failed campaigns, leaders often conduct “after-action reviews” to understand both errors and successes; individuals can mirror this practice after personal losses—writing, talking, or quietly contemplating until patterns emerge. In his own life, recounted in “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass” (1845), Douglass continually examined each defeat under slavery for clues about power, resistance, and hope. Reflection becomes a form of harvesting, ensuring that pain is not simply endured but carefully collected as wisdom.

Planting Ahead: Turning Insight Into Strategy

Once gathered, those lessons must be planted “ahead”—projected into future choices rather than stored as bitter memories. This planting is strategic: we embed new habits, boundaries, and perspectives into the path before us. Someone who has lost a job may decide to diversify skills or savings; a broken relationship might inspire clearer communication or firmer self-respect. Douglass himself transformed the sorrows of bondage into a lifelong commitment to education and abolition, using each prior loss to guide his next move. In this way, the past becomes not a chain that drags us backward, but a map we lay down in front of our feet.

From Personal Grief to Collective Renewal

Moreover, Douglass’s agricultural metaphor extends beyond the individual: seeds planted from personal losses can grow into collective change. Historical reformers often turned private wounds into public advocacy. The grief of parents who lost children in unsafe factories fueled labor reforms in the 19th century; similarly, Douglass’s own escape from slavery and subsequent writings helped cultivate the moral ground for abolition. When we share what we have learned—through conversation, art, or activism—we scatter seeds into the wider community. The harvest, then, is not only personal resilience but a society less likely to repeat the harms that caused the original loss.

Hope as the Harvest of Transformed Suffering

Ultimately, to plant lessons from loss is to wager on the future, trusting that something better can emerge from what has been broken. This is distinct from denial; it does not minimize grief but insists that grief need not be the final word. Like a farmer who knows winter is brutal yet necessary for spring, Douglass suggests that our hardest seasons can enrich the soil of our lives. Over time, patterns of learning and planting create a quiet confidence: even if new losses come, they too can yield understanding. In this way, hope becomes the enduring crop—grown not from naïveté, but from the disciplined art of transforming suffering into foresight.