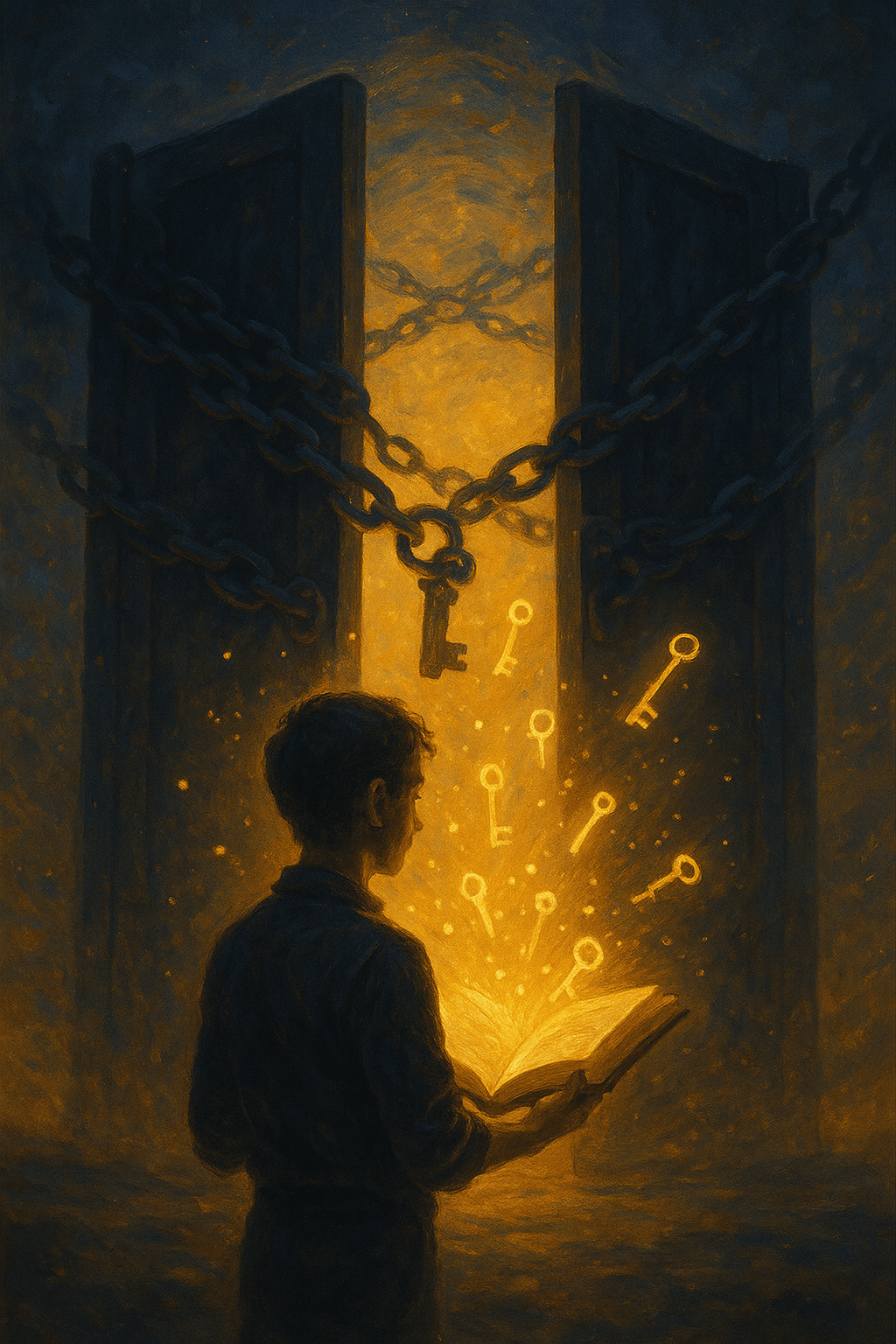

Education As the Master Key to Freedom

Claim education as your instrument; with knowledge, open the doors that bind. — Frederick Douglass

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

What does this quote ask you to notice today?

Douglass’s Life Behind the Metaphor

When Frederick Douglass urges us to “claim education as your instrument,” he speaks from the hard-earned authority of a man born into slavery who escaped through self-taught literacy. In his *Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass* (1845), he recalls how secretly learning to read transformed his sense of self, turning vague dissatisfaction into a clear understanding of injustice. Thus, his metaphor of doors that bind is not abstract rhetoric; it reflects iron barriers he personally confronted—laws, chains, and customs designed to keep enslaved people ignorant. By calling education an instrument, he frames knowledge not as a luxury but as a practical tool he once wielded to carve a path from bondage toward autonomy.

Education as Instrument, Not Ornament

Describing education as an instrument shifts it from decoration to action. Rather than a status symbol or mere credential, Douglass positions learning as something you pick up and use, like a hammer or compass. This view counters the idea that schooling exists only to impress others or secure titles. Instead, education becomes a working mechanism to question unfair rules, improve one’s livelihood, and make sense of the world. In this light, a textbook, a conversation, or even a single new concept can function as a lever, prying open constraints that once seemed immovable.

The Doors That Bind: Visible and Invisible

The “doors that bind” evoke prison cells and plantation gates, but Douglass’s phrase also gestures to less visible barriers. Legal prohibitions on teaching enslaved people to read were one kind of door; social prejudice and economic exclusion were others. Today, these doors may appear as underfunded schools, biased expectations, or digital divides that restrict who can access information. Yet, the image of a door implies that barriers have hinges—points of possible movement. Education, then, becomes the key that fits these hinges, allowing individuals and communities to push back against structures that once seemed permanently locked.

From Personal Liberation to Collective Change

Douglass’s own journey shows how personal learning can ripple outward into public transformation. Once literate, he not only escaped slavery but also became a formidable orator and abolitionist, using his knowledge of law, philosophy, and scripture to challenge pro-slavery arguments in public debates. Similarly, movements from women’s suffrage to civil rights have depended on educated voices capable of articulating injustice and envisioning alternatives. In this way, each person who claims education as an instrument becomes part of a larger orchestra, contributing to a collective effort to unbolt doors for others as well.

Claiming Knowledge in the Present Tense

Finally, Douglass’s use of the imperative—“claim”—underscores that education is not passively received; it is actively seized. Whether through formal schooling, online resources, or community mentorship, the act of claiming requires initiative and persistence, especially for those whom society sidelines. Yet as Malala Yousafzai’s advocacy for girls’ education demonstrates (*I Am Malala*, 2013), even modest learning spaces can cultivate world-changing courage. Douglass’s challenge therefore remains urgent: by deliberately pursuing and applying knowledge, individuals can turn education into a living instrument, continually unlocking new doors in their own lives and in the structures that shape us all.