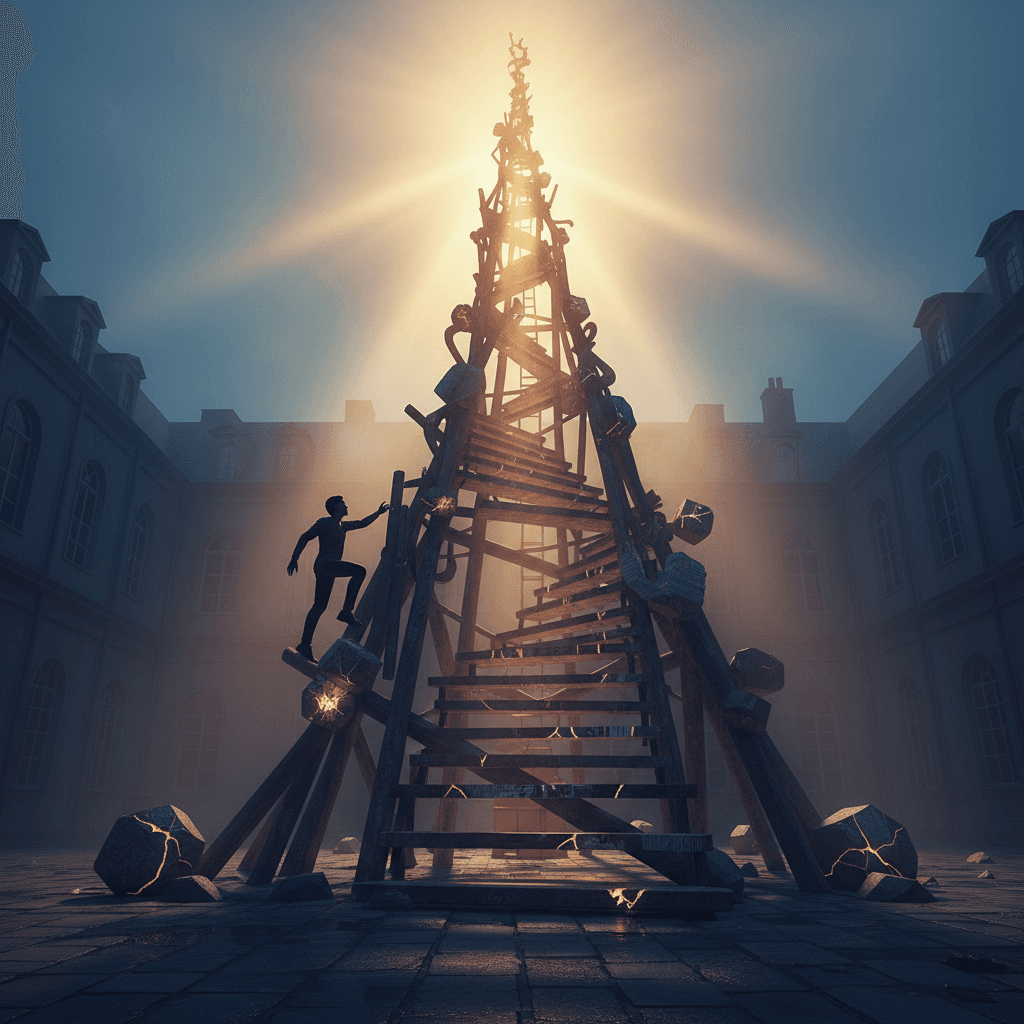

Turning Setbacks into a Structure for Growth

Turn setbacks into scaffolding; climb the structure you once feared. — Simone de Beauvoir

Reframing Failure as Material, Not Verdict

Simone de Beauvoir’s line begins by refusing the usual moral weight we attach to setbacks. Instead of treating them as a verdict on who you are, it invites you to see them as raw material—useful, shapeable, and ultimately workable. A disappointment, in this view, is not the end of a path but a component of a new one. From there, the metaphor of “scaffolding” matters: scaffolds are temporary, practical supports used to build something sturdier. The quote suggests that what looks like damage can become a support system—an interim structure that helps you rise above the level where you first fell.

The Courage to Climb What Once Terrified You

Once setbacks are reclassified as usable material, the second clause sharpens the challenge: “climb the structure you once feared.” Fear here isn’t dismissed; it becomes the very terrain of progress. What intimidated you—public failure, rejection, inadequacy—turns into a ladder rather than a wall. This echoes de Beauvoir’s existential insistence that we become ourselves through action rather than safety. Rather than waiting for fear to vanish, you move with it, using the memory of what hurt as a map of where growth is most needed. The climb is not comfortable; it is chosen.

Setbacks as a Blueprint for the Next Attempt

The idea also implies that setbacks contain information. A collapse reveals weak joints; a missed goal reveals missing skills; a broken relationship reveals unmet needs or unspoken boundaries. In that sense, a setback is diagnostic: it shows where the structure failed so you can rebuild with intention. Psychology supports this interpretive angle through research on cognitive reappraisal—reframing an event to change its emotional impact. James Gross’s work on emotion regulation (1998) shows that reappraisal can reduce distress and improve coping, making it easier to convert painful experience into specific next steps rather than generalized shame.

Scaffolding Implies Process, Not Instant Transformation

By choosing scaffolding instead of a more heroic metaphor, the quote quietly emphasizes process. Scaffolding is incremental: you assemble supports, test footing, and climb in stages. That suggests a realistic approach to resilience—progress as a series of small, structural adjustments rather than a single act of reinvention. In everyday terms, someone who bombs a presentation might rebuild by practicing with a friend, recording rehearsals, and joining a speaking group—each step a plank added to the scaffold. The fear doesn’t disappear overnight, but the structure grows sturdy enough to bear your weight.

Agency: Building with What Happens to You

A deeper thread in de Beauvoir’s thought is agency amid constraint. Life hands you circumstances you did not choose, but you still participate in what they become. “Turn setbacks into scaffolding” is an instruction in authorship: you do not control every event, yet you can control whether it becomes rubble or support. This aligns with themes in de Beauvoir’s The Ethics of Ambiguity (1947), where freedom is exercised within real limitations rather than outside them. The quote’s power is that it does not promise a world without setbacks; it insists you can still build.

From Avoidance to Ascent: A New Relationship with Fear

Finally, the image of climbing suggests a lasting shift in how you relate to fear itself. Instead of treating fear as a stop sign, you treat it as a marker for meaningful work. Over time, what once triggered avoidance becomes a familiar rung—still demanding, but no longer defining. This is how confidence often actually forms: not by proving you never fall, but by proving you can build after you do. The end result is not invulnerability; it is competence in recovery. You become someone who can ascend using the very structures built from what once brought you down.