Contentment Turns Poverty into Inner Wealth

The person who has many desires is poor; the person who is content is rich. — Indian Proverb

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

What feeling does this quote bring up for you?

A Different Measure of Rich and Poor

The proverb begins by redefining poverty and wealth as inner conditions rather than bank balances. Someone with “many desires” is described as poor because longing creates a constant sense of lack, even when possessions are plentiful. In contrast, the content person is rich because satisfaction reduces the felt distance between what one has and what one wants. This shift in measurement matters because it relocates the center of life from external accumulation to internal sufficiency. As a result, the saying doesn’t deny material hardship; instead, it argues that the experience of deprivation can be intensified—or eased—by the mind’s appetite.

Desire as a Self-Refilling Hunger

Moving from definition to mechanism, the proverb highlights how desire tends to multiply. Each fulfilled want often reveals a new target: a larger home, a newer device, a higher status. Like drinking salt water, the act of satisfying certain cravings can increase thirst rather than end it, leaving the person perpetually “poor” in the emotional sense. This helps explain why two people with the same income can feel radically different about their lives. One experiences their situation as a platform for endless upgrades; the other experiences it as adequate, and that adequacy functions like wealth—stable, usable, and quietly reassuring.

Contentment as Active Practice, Not Passivity

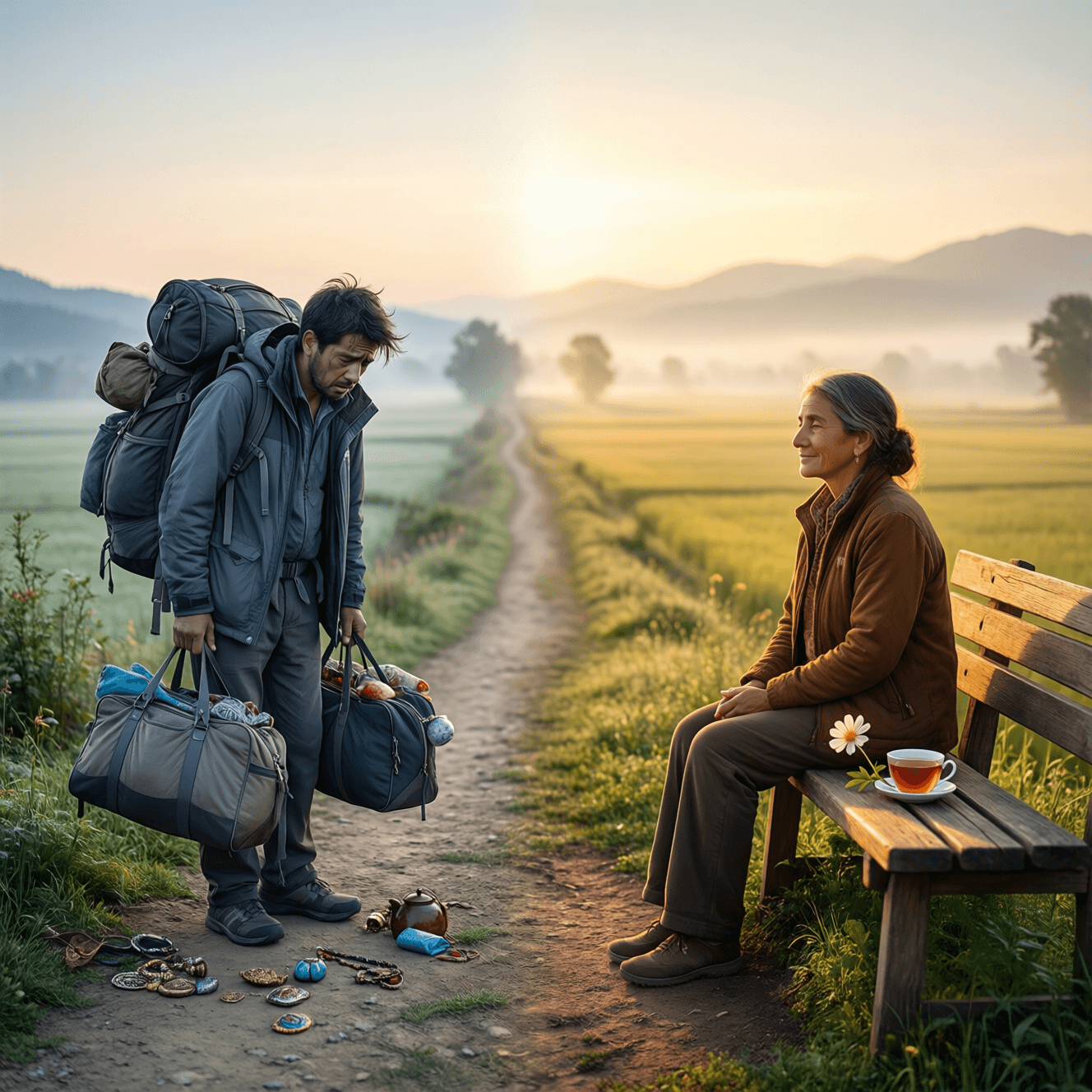

Yet contentment here is not resignation or indifference. The proverb points to a deliberate stance: recognizing what is already sufficient while still acting wisely in the world. In that sense, contentment is closer to mastery than to surrender—it governs desire rather than being governed by it. Consider a simple anecdote: a traveler with a small bag who knows exactly what they need moves lightly and freely, while another with excess luggage feels burdened and anxious about loss. Similarly, contentment trims life to what genuinely matters, and that clarity begins to resemble riches.

Philosophical Echoes Across Traditions

From this perspective, the proverb aligns with a broader philosophical lineage. The Upanishads often frame peace as freedom from craving, and the Bhagavad Gita (c. 2nd century BC–2nd century AD) praises the person who is steady amid desire and fear (e.g., 2.70–2.71). In a different idiom, Epictetus’ Discourses (c. 108 AD) similarly argues that wealth depends less on what you have than on what you can do without. These echoes reinforce the same core idea: wanting less can be a form of power. When desire stops dictating identity, a person becomes harder to manipulate—by envy, trends, or comparison.

The Social Trap of Comparison

Next, the proverb implicitly critiques comparison, one of the greatest engines of desire. Modern life makes it easy to view other people’s curated success and turn it into a personal deficit. When desire is fueled by status rather than need, “poverty” becomes a moving target: there is always someone richer, newer, more admired. Contentment interrupts that cycle by shifting attention from relative standing to lived experience—health, relationships, time, purpose. In doing so, it offers a kind of equality: even in unequal societies, the inner capacity to savor what is good can lessen the humiliation that comparison tries to impose.

A Practical Wealth That Endures

Finally, the proverb points toward a durable kind of richness: the ability to enjoy what one has, to sleep without the agitation of endless wanting, and to make decisions without desperation. This “wealth” is portable—it can’t be stolen, inflated away, or made obsolete by the next upgrade. At the same time, the teaching can coexist with ambition. One can work to improve circumstances while refusing to let happiness be postponed to a future purchase or achievement. In that balance, desire becomes a tool rather than a master, and contentment becomes not an endpoint but a steady source of inner abundance.