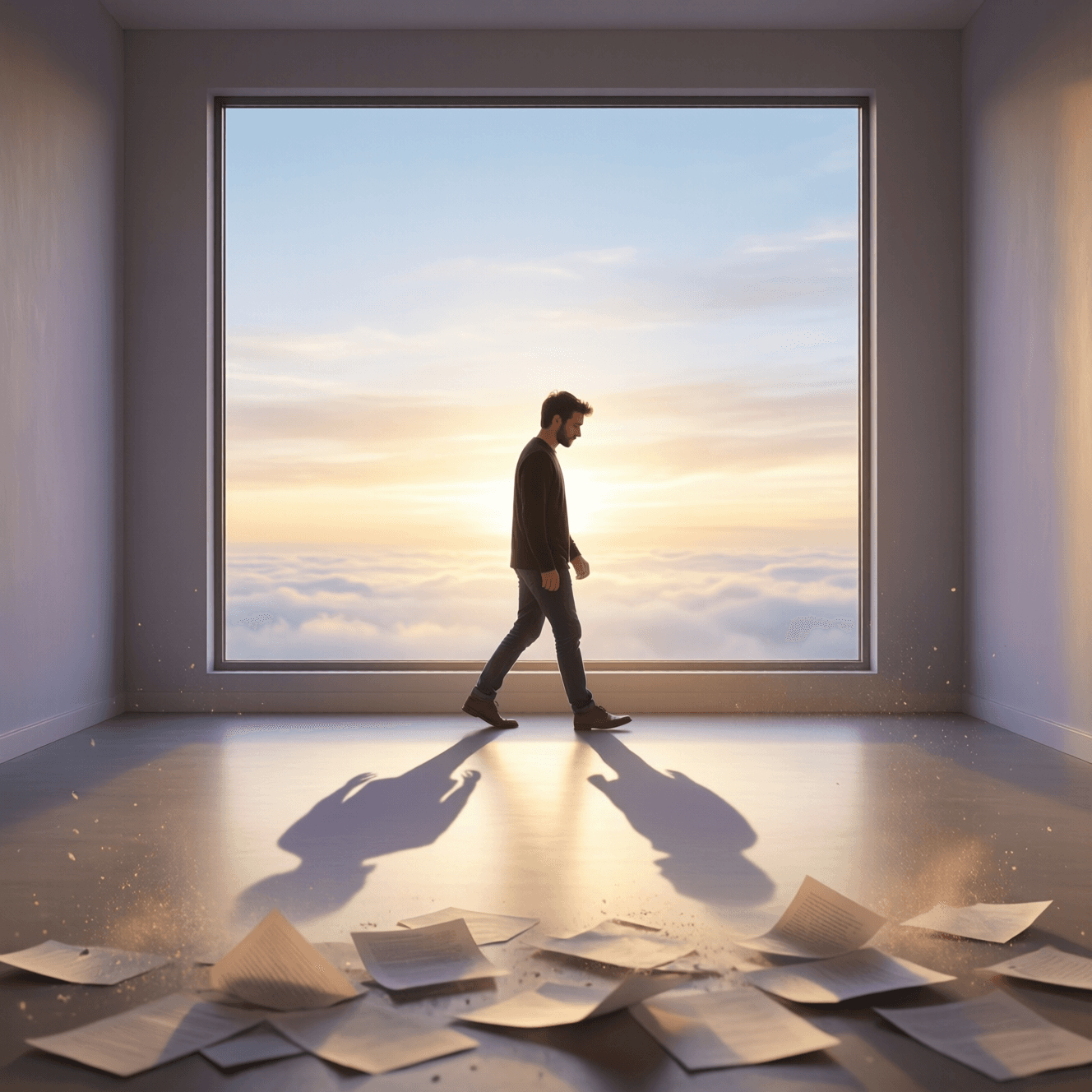

Freedom to Change in Every Moment

You are under no obligation to be the person you were five minutes ago. — Alan Watts

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Where does this idea show up in your life right now?

A Radical Permission to Evolve

Alan Watts’s line opens with a startling kind of relief: you don’t owe continuity to anyone—not even to yourself. Rather than treating identity as a contract signed in the past, he frames it as something closer to a living process. In that sense, “five minutes ago” becomes symbolic of any prior version of you: yesterday’s opinions, last year’s goals, or the roles you learned to perform for acceptance. From this starting point, the quote invites a gentle but decisive shift in mindset. If you are not obligated to remain who you were, then change is not a betrayal; it is a legitimate response to new insight, new information, or new honesty about what you actually feel.

Identity as a Process, Not a Statue

Building on that permission, Watts’s broader philosophy often treats the self as fluid rather than fixed, echoing themes in his lectures and writings such as *The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are* (1966). The “you” you defend so fiercely can be understood as a pattern of habits, memories, and narratives—real enough to experience, but not permanent in the way we imagine. Seen this way, consistency becomes less of a moral demand and more of a practical preference. You can still have values and commitments, yet recognize that the person holding them is continually being updated by experience, like a river that remains “the same” only by constantly moving.

How the Past Becomes a Cage

Next comes the reason this message matters: we often let our past harden into an obligation. A comment you made in a meeting, a major you chose, a reputation you gained, or an identity you announced can quietly become a cage, because changing might look like weakness or hypocrisy. Watts undercuts that fear by challenging the idea that your earlier self has authority over your current one. Consider a small, familiar scenario: someone says, “But you used to love that,” or “You always said you’d never do this.” The quote offers a calm reply—yes, that was true then, and now something else is true. Growth can look like contradiction from the outside while feeling like alignment from the inside.

Responsibility Without Self-Imprisonment

However, freedom to change is not the same as freedom to evade accountability. The quote doesn’t erase consequences; it reframes identity. You can acknowledge what you did five minutes ago while also refusing to be defined by it forever. In practical terms, this means owning mistakes without adopting them as a permanent label. This balance matters because people sometimes confuse “I can change” with “Nothing counts.” Watts’s point can be read more constructively: the past informs the present, but it does not dictate it. Responsibility becomes something you practice—making repairs, telling the truth, choosing better—rather than a lifelong sentence to remain the person who acted without wisdom.

Psychological Flexibility and Well-Being

From there, the quote aligns with a modern psychological theme: psychological flexibility—the capacity to adapt your thinking and behavior in response to what is happening now. Approaches like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, developed by Steven C. Hayes and colleagues (e.g., Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson’s *Acceptance and Commitment Therapy*, 1999), emphasize loosening rigid self-stories (“I’m just this kind of person”) to make room for more effective choices. When you aren’t obligated to remain an old self-concept, you can act based on current values rather than old defenses. The result is often less shame and more agency: you’re not trying to protect a fixed identity, but to live more honestly in the present.

Practicing the Moment-by-Moment Reset

Finally, Watts’s insight becomes most powerful when treated as a practice rather than a slogan. The “five minutes ago” framing suggests that renewal is always available in small increments: you can revise a harsh judgment, apologize sooner, change your mind mid-conversation, or step out of an unhelpful role without waiting for a dramatic life overhaul. In everyday life, this might look like pausing before you repeat a familiar pattern—doom-scrolling, snapping defensively, self-sabotaging—and choosing a different next action. The quote doesn’t promise that change is easy; it insists that change is permitted. And once permission is granted, the present moment becomes a doorway rather than a verdict.