Archimedes and the Power of Leverage

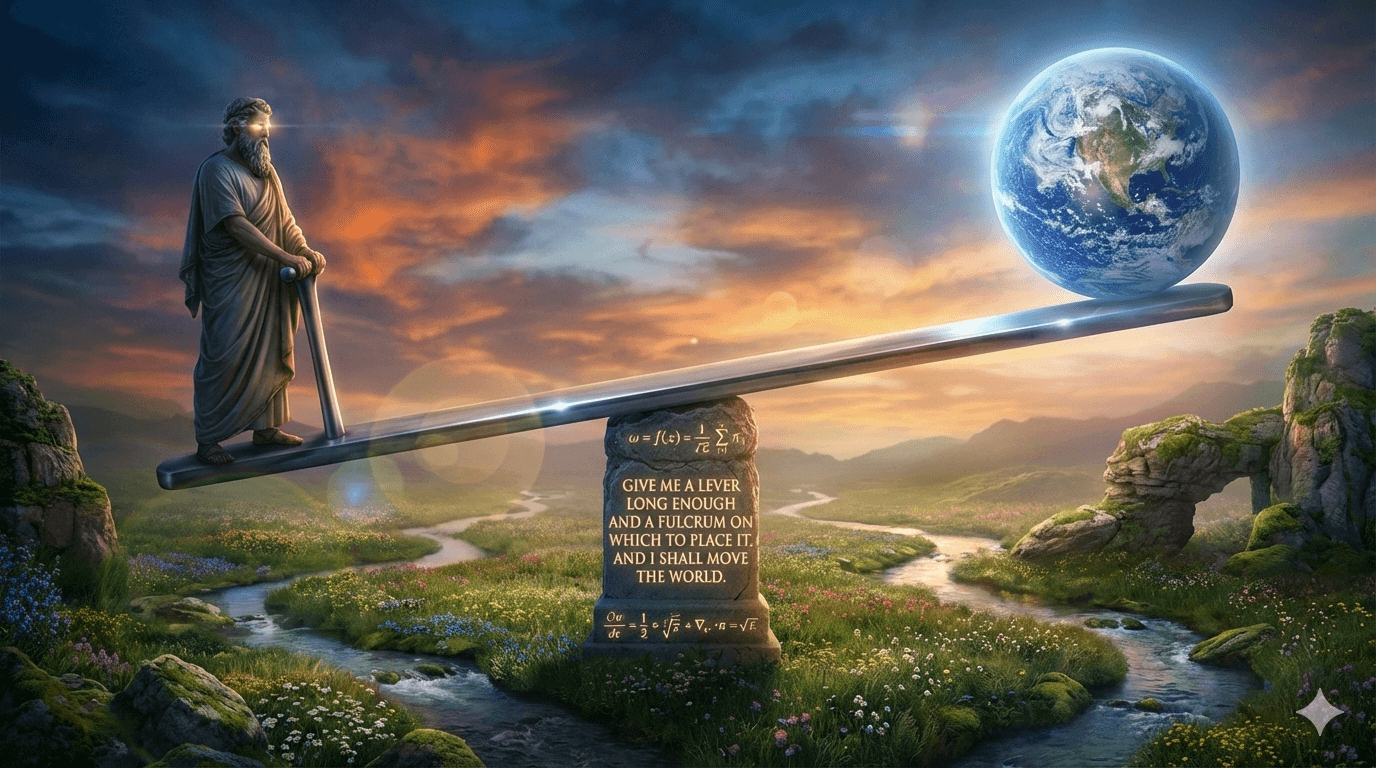

Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world. — Archimedes

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Why might this line matter today, not tomorrow?

A Bold Claim, Grounded in Mechanics

Archimedes’ famous line sounds like pure bravado, yet it is really a compact summary of a physical law: with sufficient mechanical advantage, a small force can accomplish an immense task. By invoking a lever “long enough” and a fulcrum placed just right, he points to the way geometry and force can be arranged to multiply human effort. From the outset, the quote invites a shift in perspective. Instead of asking how strong a person must be to “move the world,” it asks how cleverly the system can be designed so strength becomes almost secondary to structure.

The Principle of the Lever

At the heart of the statement is the law of the lever, later formalized through torque: the turning effect of a force depends on both the force and its distance from the pivot. In simple terms, pushing farther from the fulcrum increases your turning power, even if your push stays the same. That is why a crowbar can lift what hands alone cannot. Building on this, Archimedes is highlighting a tradeoff rather than a free miracle: the longer lever lets you apply less force, but you must move your end through a greater distance. The world “moves,” but only because you travel farther to make it happen.

The Fulcrum as the Hidden Constraint

The fulcrum is more than a prop; it is the condition that makes leverage possible. Without a stable pivot and a firm base, a long lever is just an unwieldy stick. Archimedes quietly assumes an unshakeable point of support—an assumption that reveals the real limitation behind the bravura. This is why the quote remains so memorable: it pairs grand ambition with a subtle requirement. Power comes not only from extending reach, but from finding or creating the one place that won’t slip when everything else resists.

Legend, Demonstration, and Ancient Engineering

Ancient writers describe Archimedes as a master of practical mechanics as well as theory. Plutarch’s *Life of Marcellus* (1st–2nd century AD) recounts that Archimedes demonstrated mechanical advantage by moving a heavily laden ship with a system of pulleys, illustrating how a small input could control a massive load. Whether embellished or not, the story captures the spirit of the lever claim: the point was to show principle through spectacle. From there, it’s easy to see why later generations treated the quote as a banner for engineering itself. It encapsulates the idea that understanding forces can outperform brute strength.

A Metaphor for Strategy and Systems

Beyond physics, the lever becomes a metaphor for influence: small actions can have large effects when applied at the right point in a system. In politics, technology, or organizations, “leverage” often means identifying a bottleneck, incentive, or dependency where a modest intervention cascades into major change. Yet the metaphor keeps the original caution intact. Just as a physical lever needs a secure fulcrum, strategic leverage depends on stable assumptions—reliable information, institutional support, or trust. If the pivot shifts, the same force produces far less movement.

Modern Echoes: From Machines to Multipliers

In contemporary life, Archimedes’ insight appears wherever tools amplify effort—hydraulic jacks, cranes, gear trains, and even software that scales one person’s work to millions of users. Each case follows the same pattern: arrange a mechanism so that input is transformed, redirected, or magnified into output. Ultimately, the quote endures because it compresses an entire worldview into one sentence. Master the geometry of effort—find the fulcrum, choose the right length—and what once seemed immovable becomes, at least in principle, negotiable.