Freedom: The Responsibility Behind the Right to Err

Freedom is the right to be wrong, not the right to do wrong. — Ayn Rand

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

What feeling does this quote bring up for you?

Defining True Freedom

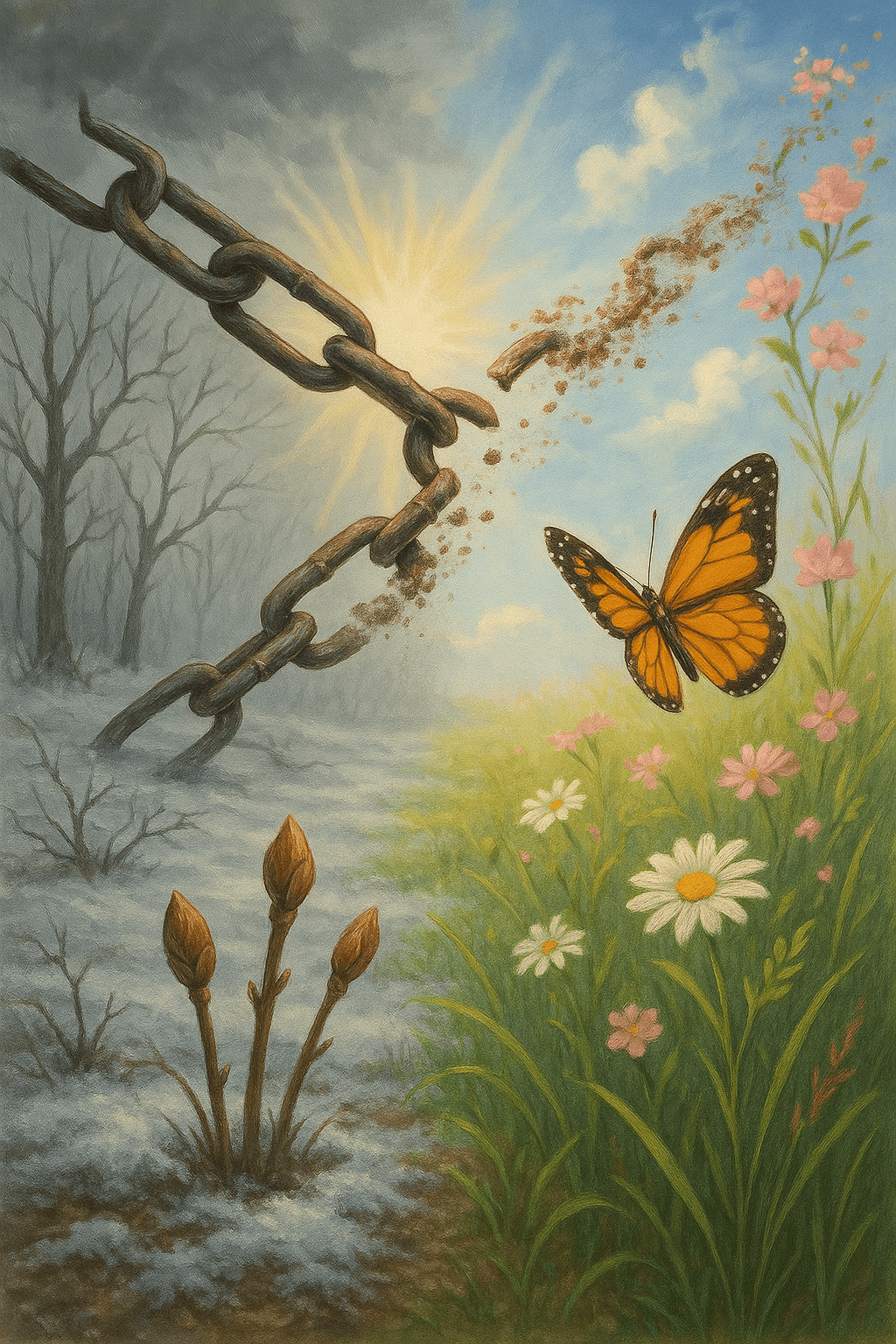

Ayn Rand’s quote draws an important distinction: freedom is not an unbounded license but a nuanced right tied to personal accountability. The ‘right to be wrong’ means individuals are free to hold mistaken beliefs or make errors in judgment without interference. However, this does not extend to the ‘right to do wrong’—acting in a way that causes harm or infringes upon others’ rights. This subtlety is central to the philosophical foundations of liberty.

Moral Boundaries and Social Order

Building upon this distinction, societies have always wrestled with balancing individual liberty and communal welfare. John Stuart Mill, in his seminal work ‘On Liberty’ (1859), echoes a similar sentiment: personal freedom should extend until it harms another. Rand’s perspective reinforces the idea that civil society thrives not by policing thoughts or honest mistakes, but by drawing a clear line when actions transgress ethical or legal bounds.

Learning Through Error

Transitioning to human growth, the right to be wrong underscores the value of learning from mistakes. Thomas Edison’s famous adage about discovering ‘10,000 ways that won’t work’ enshrines error as a driver of innovation. Granting people the autonomy to be mistaken fosters critical thinking, creativity, and resilience—principles essential not only to individual development but to societal progress.

Freedom and Legal Responsibility

While freedom makes room for error, it is ultimately anchored by responsibility. Laws and ethical codes distinguish between blameless misjudgments—protected under freedom—and wrongful acts, which demand accountability. For example, in criminal law, intent and harm delineate innocent errors from punishable offenses. This framework preserves liberty while upholding justice, illustrating Rand’s view in practical terms.

The Challenge of Practicing Principled Liberty

Finally, embracing this interpretation of freedom requires cultural maturity. Allowing room for errors of conscience or thought can be uncomfortable in polarized times, yet it provides the bedrock for open debate and pluralism. By refraining from equating being wrong with doing wrong, societies can nurture an environment where divergent opinions coexist—even as clear boundaries prevent genuine wrongdoing. This delicate balance, championed by thinkers from Voltaire to Rand, lies at the heart of a just and free society.