Perfection Through the Discipline of Thoughtful Subtraction

Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away. — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

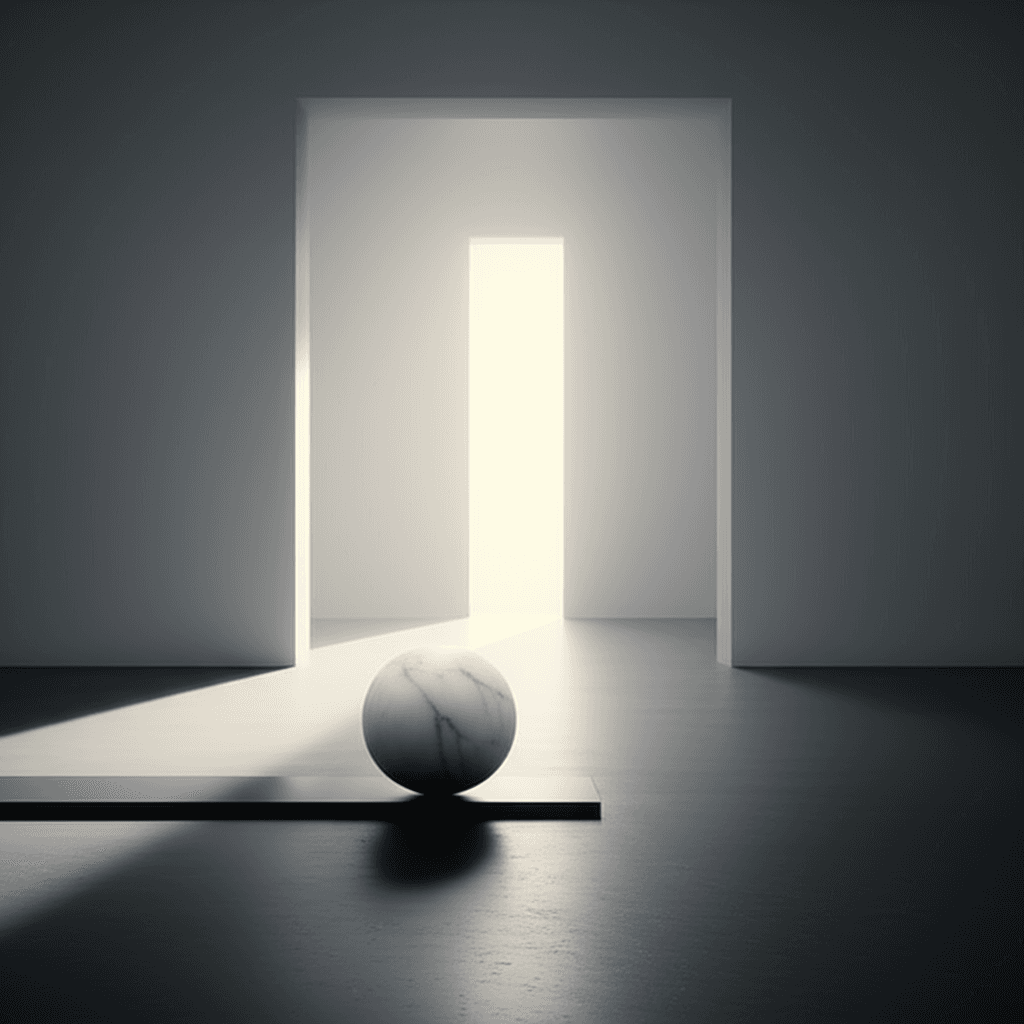

Sculpting Essence, Not Adding Ornament

Saint‑Exupéry’s claim reframes perfection as an unveiling rather than an accumulation. Like a sculptor removing marble to let the figure emerge, the work is not austerity for its own sake but clarity: every element must earn its place or be removed. The question shifts from ‘What else can we add?’ to ‘What obscures the purpose?’. From this pivot, the principle travels smoothly from cockpit to studio, from philosophy to code.

Aviator Origins of a Minimal Creed

Written by a pioneering pilot, the aphorism carries flight’s pragmatism. In Terre des hommes / Wind, Sand and Stars (1939), Saint‑Exupéry recounts desert landings and night navigation where extra weight, superfluous gauges, and fussy procedures endangered lives. In the cockpit, each instrument answers a single, necessary question; redundancy serves safety, not vanity. Thus subtraction is not decorative minimalism; it is survival logic refined by wind, cold, and time.

A Philosophical Lineage of Less

Historically, this ethos echoes older maxims. William of Ockham’s razor (14th c.) cautions against multiplying entities beyond necessity, a methodological preference that trims explanations until they are sufficient. In design, Mies van der Rohe’s ‘less is more’ and the Bauhaus program pursue form disciplined by function. The kinship suggests that subtraction is not a fad but a repeatable route to intelligibility across domains.

Design and Engineering: Reliability by Reduction

In practice, fewer parts often mean fewer failure modes. Reliability engineers quantify this; each component introduces interfaces and potential faults. John Gall’s Law in Systemantics (1975) observes that complex systems that work evolve from simpler systems that worked. Likewise, the Toyota Production System targets muda—waste—in motion, inventory, and overprocessing, letting value flow once impediments are removed. The result is not bareness but resilience and serviceability.

Writing and Software: Deletion as Design

Crafts of language and software formalize the same move. Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style (1959) urges us to omit needless words, turning drafts into messages. In code, Extreme Programming’s YAGNI (Beck, 1999) warns against speculative features, while Dijkstra’s 1984 essays praise simplicity as a moral duty. Refactoring then becomes sculpting: we delete duplication, collapse abstractions, and leave behind only the behavior users actually need.

Avoiding the Trap of Shallow Minimalism

Yet subtraction has a failure mode: pretty emptiness. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. distinguished shallow simplicity from the hard‑won simplicity ‘on the other side of complexity’. Remove too much, and we amputate affordances, safety margins, or context; remove too little, and we drown purpose in clutter. Thus the art resides in tracing the boundary where removal ceases to clarify and begins to distort.

A Practical Subtraction Workflow

Therefore, a workable method starts with purpose. Define the job to be done; inventory parts against that purpose; then stage subtractions as reversible experiments. After each removal, test in real conditions, listening for friction, confusion, or risk. Keep the last element that still changes the outcome, and document why it remains. Over time, this cadence yields products, processes, and pages that feel inevitable—because nothing unnecessary is left to take away.