Saving Lives Before Arguing About Souls

Created at: August 26, 2025

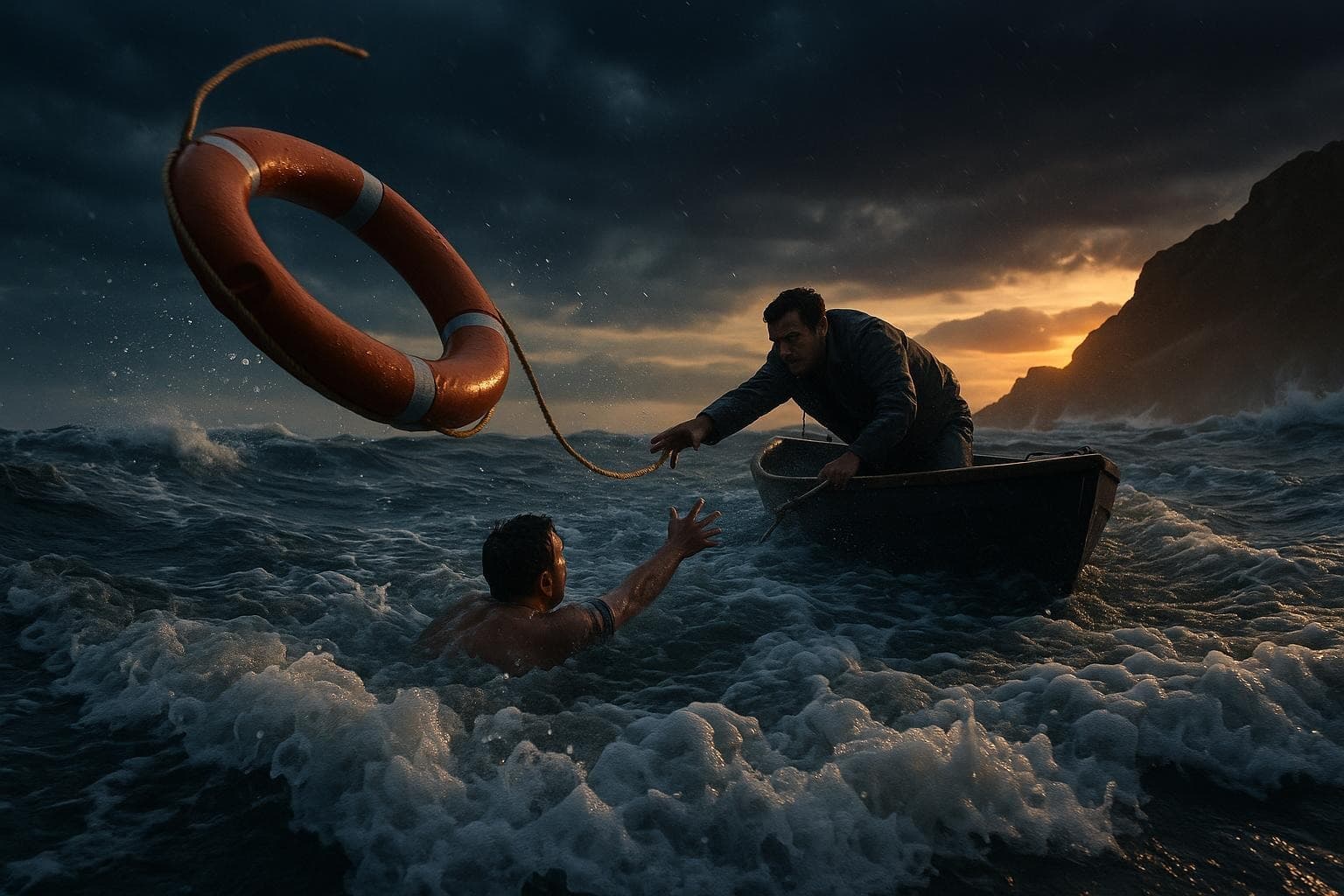

When a man is drowning, whether he is a pastor or a pagan, I won't waste time arguing about his soul. — Chinua Achebe

The Imperative of Immediate Rescue

Achebe’s image is stark: a drowning man cannot be saved by metaphysics. The point is not to denigrate belief, but to rank duties—first secure breath, then discuss doctrine. In emergencies, time compresses ethics into action; mercy, not metaphysical certainty, becomes the first obligation. The parable of the Good Samaritan likewise suspends identity checks to prioritize aid (Luke 10:25–37), suggesting a long tradition that endorses help before judgment. Achebe’s phrasing, therefore, is less a dismissal of the soul than a discipline of attention: life precedes labels.

Beyond Pastor and Pagan

From this urgency follows a refusal to let categories define compassion. The contrast between pastor and pagan exposes how moral worth is often filtered through religious or cultural membership. Achebe’s fiction illustrates the harm of such lenses; in Things Fall Apart (1958), binary thinking—colonizer and colonized, convert and traditionalist—fractures communities. By invoking two charged identities at the water’s edge, he dissolves their difference in the face of shared vulnerability. Thus, the drowning body becomes a counter-argument to sectarian reflexes.

Achebe’s Humanism in Critique

Building on that insight, Achebe’s essays insist that storytelling must restore the human center where ideology has erased it. In “An Image of Africa” (1977), he critiques Conrad’s Heart of Darkness for reducing Africans to background, arguing that literature shapes whether we recognize a person as fully human. The drowning-man dictum is the ethical twin of that literary stance: first, acknowledge a life; then, if necessary, debate frameworks. In both arenas, Achebe resists abstraction that costs a person their claim on our care.

Lessons From War and Famine

Moreover, Achebe’s life gave him reasons to distrust delayed compassion. During the Nigerian Civil War, he witnessed suffering that demanded airlifts, not arguments. His memoir There Was a Country (2012) recounts how starvation and displacement turned political disputes into matters of bare survival. In such contexts, moral triage becomes unmistakable: feed the child, stop the bleeding, secure passage. The quote reads, then, as distilled experience—an ethic forged where hesitation proved deadly and mercy had to move faster than ideology.

The Ethics of Triage and Practice

Translating this into practical terms, emergency care teaches the same order: airway, breathing, circulation—do first things first. Philosophers may debate utilitarian and deontological priorities, yet in crisis their prescriptions converge on immediate harm reduction. Achebe’s phrasing turns that clinical wisdom into a civic principle: societies should design institutions that reach for the hand in the water before convening tribunals about belief. Action, in this view, is not anti-intellectual; it is the most honest beginning of moral thought.

Contemporary Applications Beyond the Riverbank

Extending the metaphor, today’s public square often treats every need as a referendum on worthiness—health care, addiction services, refugee support. Achebe urges the opposite sequence: deploy aid first, debate policy afterward. When communities stock naloxone, fund shelters, or open disaster relief without purity tests, they enact his principle that lives are not bargaining chips. Even online, where outrage can eclipse outcomes, the standard becomes simple: did someone get pulled from the water, or did we merely perfect our arguments?

Debate After the Rescue

Finally, Achebe does not abolish moral or theological conversation; he reschedules it. Once the rescued can breathe, we have time to ask deeper questions about meaning, belief, and justice. In fact, post-rescue dialogue is often wiser, informed by gratitude and humility rather than panic or pride. The sequence matters: save, then speak. By ending where we began—the drowning man—we recover a humane order of operations that dignifies both body and soul by refusing to let either be lost to delay.