Climb Higher to See the Wider World

Created at: August 30, 2025

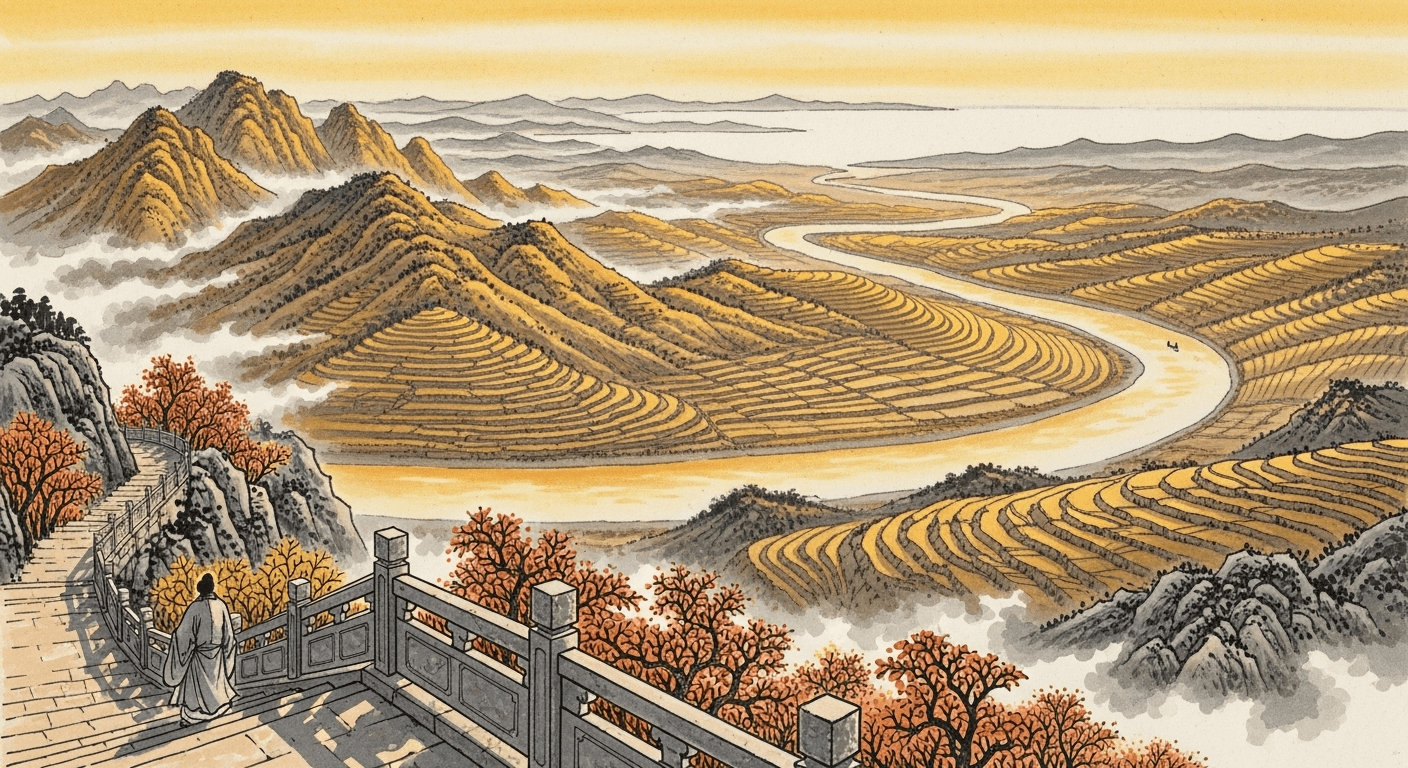

The sun beyond the mountain glows; The Yellow River seaward flows. You can enjoy a grander sight, By climbing to a greater height. -- Wang Zhihuan (Tang Dynasty)

From Landscape to Lesson

Wang Zhihuan begins with immensity: the sun slipping beyond mountain ridges and the Yellow River pressing toward the sea. These images situate us in a world of grand scales and unstoppable motion. Yet, as the scene expands, the poem pivots from description to counsel: if you want a greater view, ascend another story. The shift converts spectacle into instruction, suggesting that perspective is not granted but earned. In this way, the poem quietly argues that vision—literal and figurative—depends on our willingness to rise.

Tang Quatrain’s Precision and Turn

Formally speaking, the poem is a five-character quatrain (jueju), a Tang-dynasty form prized for density and balance. Its first couplet pairs vast elements—“white sun” and “Yellow River”—with symmetrical verbs that convey continuation: glowing, flowing. The closing lines then perform the genre’s signature turn, moving from panorama to principle. As in Wang Zhihuan’s “On the Stork Tower” (c. 8th century), the compression is the message: economy of words becomes expansiveness of meaning, with the final exhortation radiating back to illuminate the entire scene.

The Stork Tower’s Vantage

Situated on the Yellow River’s edge in present-day Yongji, Shanxi, the Stork Tower offered travelers a literal height from which to look across water and mountain. Later eras rebuilt the site, but the poem’s enduring power lies less in bricks than in the stance it prescribes: climb, and the world discloses itself. Li Bai’s “Viewing the Waterfall at Mount Lu” (c. 8th century) similarly expands scale to reset human perspective, yet Wang’s spare instruction is more pointed—it makes sight an ethical act of ascent.

Perspective, Physics, and Power

Extending the image, even basic optics agrees: as height increases, the visible horizon grows (a common approximation is d ≈ 3.57√h km, with h in meters). The poem intuits this truth and reframes it as a principle of knowledge. To see farther in any field, we must change our vantage—seeking mentors, acquiring methods, or stepping outside our habitual frames. Thus the climb is not bravado but method: a disciplined way to convert elevation into understanding.

A Cultural Ethic of Aspiration

Within Chinese moral imagination, Wang’s final line—欲穷千里目,更上一层楼—became proverbial, echoing the classical emphasis on self-cultivation. Xunzi’s “Encouraging Learning” (3rd century BCE) insists, “Without accumulating small steps, one cannot reach a thousand miles.” Together they propose a coherent ethic: breadth of vision follows from incremental ascent. The poem therefore harmonizes aesthetic awe with a Confucian cadence of effort, where each additional floor synthesizes patience, discipline, and a widening sense of the world.

Modern Resonances in Growth and Work

In contemporary life, the poem maps neatly onto practices that enlarge capacity. Carol Dweck’s research on growth mindset (2006) shows that embracing challenge expands what we can perceive and do; Anders Ericsson’s work on deliberate practice (1993) likewise demonstrates how structured difficulty elevates performance. By treating elevation as repeated, intentional steps, Wang’s counsel becomes practical: seek the higher seminar, the tougher dataset, the broader coalition. Each climb yields a grander sight—and, in turn, invites the next ascent.