Endurance and Resolve in Classical Chinese Lore

“Sleeping on firewood and tasting gall, with three thousand Yue spears he swallowed Wu; Breaking his cauldrons and sinking his boats, the hundred passes of Qin at last fell to Chu.” — Anonymous

Two Idioms, One Lesson

The couplet binds two celebrated idioms into a single arc of triumph through hardship. Sleeping on firewood and tasting gall evokes a ruler’s self-imposed austerity; breaking cauldrons and sinking boats signals a deliberate severing of retreat. Together, they argue that patience and ferocity, long-term endurance and decisive action, are complementary virtues. Rather than praising recklessness, the lines propose a sequence: first cultivate resilience, then commit without escape routes. In this way, the verse sets the stage for paired historical episodes that illustrate how inner steel and outward resolve can bend the course of states.

Goujian’s Bitter Gall and Patient Revenge

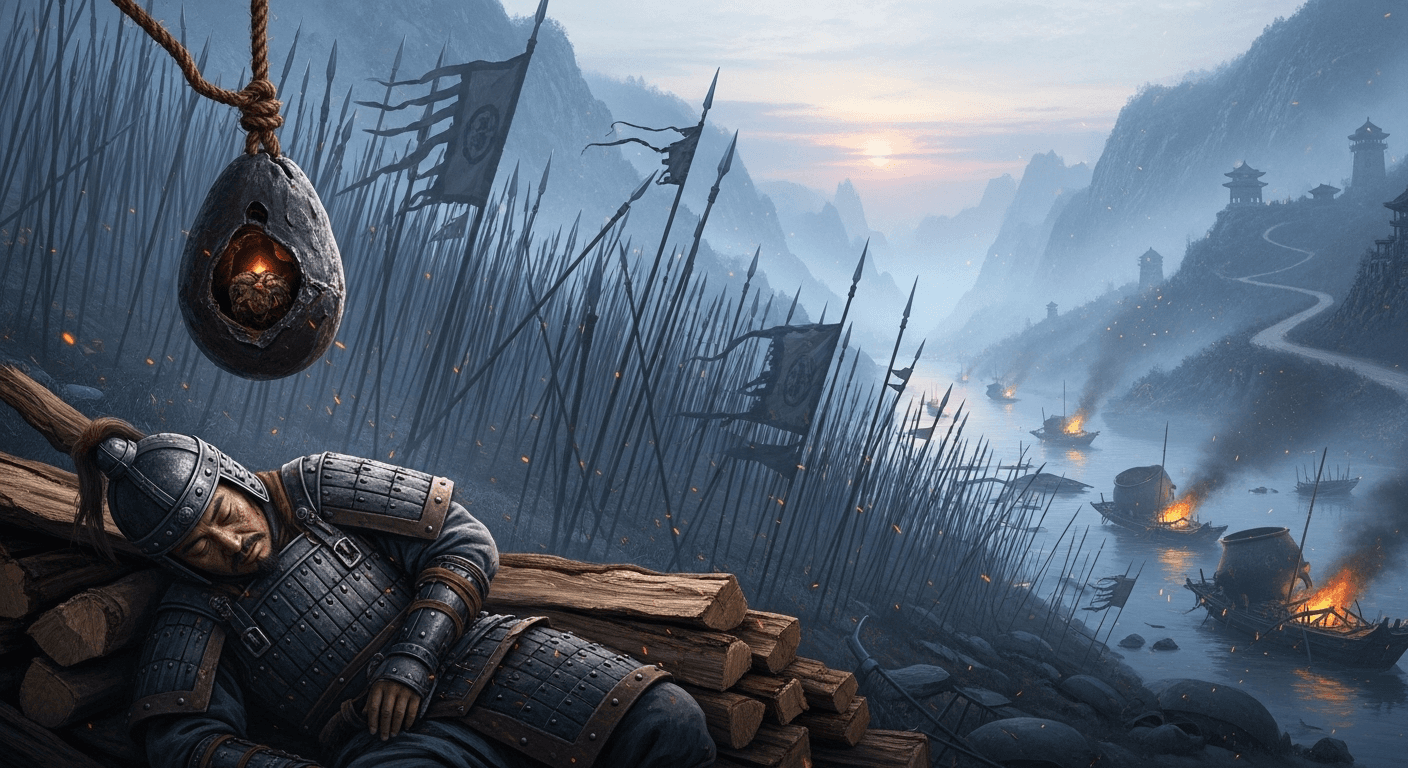

The first image recalls King Goujian of Yue, who, after defeat and humiliation at the hands of Wu’s King Fuchai, lived austerely, slept on brushwood, and tasted a hanging gall bladder to keep disgrace vivid. Yue Jue Shu (c. 1st century CE) preserves this tale of self-discipline culminating in Yue’s conquest of Wu (473 BCE). The moral is not vengeance alone but the forging of character under constraint: by rehearsing pain, Goujian kept purpose sharp while rebuilding strength. As the couplet suggests, memory of hardship can be a strategic asset, transforming personal resolve into national revival through steady planning and calibrated patience.

Xiang Yu’s No-Return Gamble at Julu

The second image shifts from austerity to irrevocable commitment. During the struggle against Qin, the Chu commander Xiang Yu reportedly ordered his forces to break their cauldrons and sink their boats before the Battle of Julu, ensuring that victory was the only path to survival. Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian (c. 94 BC) narrates how this gamble galvanized the army, helping shatter Qin’s grip and hastening its collapse (207 BCE). The couplet’s hyperbole about the hundred passes of Qin underscores that a single act of resolve can cascade through a tottering regime, turning a tactical choice into a strategic watershed.

Commitment Devices and the Psychology of Grit

Linking these episodes, modern thought frames them as distinct commitment mechanisms. Goujian’s ritual of hardship resembles a self-binding reminder, aligning daily behavior with distant goals, much as Thomas Schelling described strategic commitments that make backsliding costly (The Strategy of Conflict, 1960). By contrast, Xiang Yu’s destruction of supplies is a classic burn-the-bridges device that converts hesitation into action by eliminating alternatives. Contemporary research on grit and deliberate practice likewise finds that sustained effort paired with clear constraints can outstrip talent alone, provided the constraints are chosen, not imposed, and are aligned with a coherent long-range purpose.

Cross-Cultural Echoes of No-Retreat Resolve

The motif of cutting off retreat recurs worldwide. Hernán Cortés famously scuttled (rather than literally burned) his ships in 1519 to prevent desertion, a gesture later summarized as burn the boats. In Islamic tradition, Tariq ibn Ziyad is said to have burned his vessels in 711 before the conquest of al-Andalus, though historians debate the story’s details. These parallels suggest a universal intuition: when options multiply, resolve can waver; when paths narrow, effort intensifies. Yet, as in the Chinese sources, these acts worked best when paired with sound logistics and morale, not as bravado alone.

Resolve’s Costs and the Need for Prudence

Still, ruthless commitment can curdle into overreach. Xiang Yu, triumphant at Julu, later fell to Liu Bang after strategic miscalculations and attrition leading to Gaixia (202 BCE), a caution recorded by Sima Qian. Behavioral studies on escalation of commitment warn how sunk costs can trap leaders in failing courses (see Barry Staw, 1976). The couplet therefore invites a balanced reading: embrace Goujian’s disciplined patience to build capacity, and deploy Xiang Yu’s no-return resolve only when timing, supply, and morale align. Used together and with prudence, endurance and commitment become not just slogans but durable statecraft.