Stoic Acceptance Paired With Deliberate, Steady Action

Accept what you cannot change, then move with steady hands to change what you can — Marcus Aurelius

The Stoic Groundwork

At the heart of the line lies Marcus Aurelius’s core Stoic rhythm: first accept, then act. In Meditations (c. 180 CE), he repeatedly urges ‘willing acceptance’ of what nature sends and ‘unselfish action’ in the present moment, treating fate as the canvas and duty as the brush. Acceptance, in this sense, is not resignation but lucid orientation; it clears mental fog so that action can proceed without panic or self-pity. Thus the sentence divides our energy wisely: we let go of the wind, then set our sail.

The Dichotomy of Control

This rhythm rests on a famous Stoic distinction. Epictetus’s Enchiridion 1 differentiates between what is up to us (judgment, intention, effort) and what is not (reputation, weather, outcomes). By aligning the will with the former and consenting to the latter, we avoid frantic, misdirected toil. The idea reappears centuries later in Reinhold Niebuhr’s Serenity Prayer (c. 1933–42), which asks for the serenity to accept, the courage to change, and the wisdom to know the difference. In both frames, clarity precedes courage: we see the boundary, then we step forward within it.

Why Steady Hands Matter

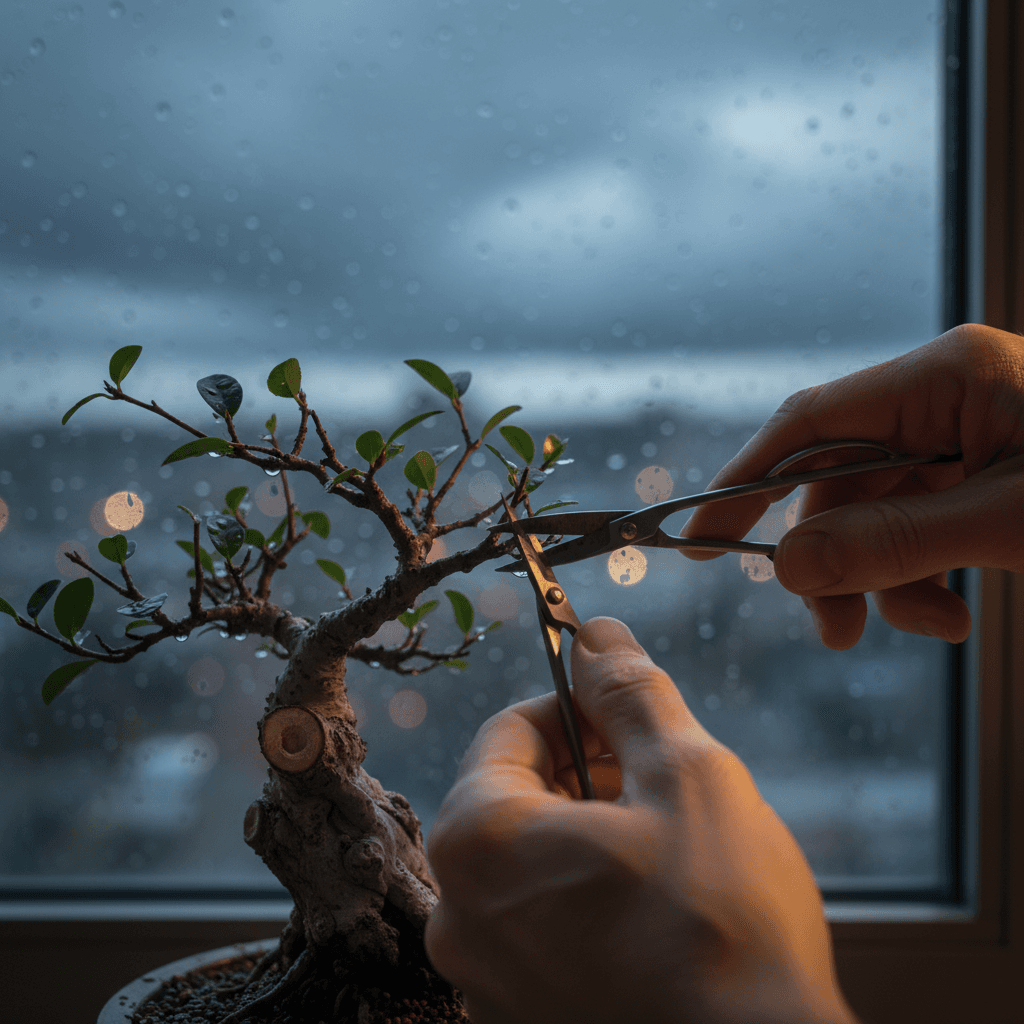

Having accepted limits, the manner of action becomes crucial. Marcus’s phrase ‘steady hands’ evokes calm competence rather than hurried bravado. Craftspeople and soldiers share the maxim ‘slow is smooth, smooth is fast,’ reminding us that composure often shortens the path to results. Stoics trained for this steadiness through premeditatio malorum—envisioning setbacks in advance—so that surprise would not fray their judgment. In modern terms, steady hands are a nervous system regulated enough to keep perception wide, decisions precise, and motion economical.

Lessons from History and Craft

Consider Apollo 13 (1970), when NASA’s Mission Control methodically ‘worked the problem’ after an oxygen tank exploded; acceptance of damage made room for inventive, measured action that brought the crew home. Or recall Captain Chesley Sullenberger’s Hudson River landing (2009): after bird strikes killed both engines, he followed checklists and judgment with unshaken composure. Atul Gawande’s The Checklist Manifesto (2009) shows why such steadiness scales: simple, repeatable structures transform anxiety into reliable execution. Across domains, the pattern holds—clear-eyed acceptance, then disciplined doing.

Psychology and Resilience Today

Modern research echoes the Stoics’ intuition. Julian Rotter’s locus-of-control studies (1966) link well-being to focusing effort where it truly counts, while Aaron T. Beck’s cognitive therapy (1979) teaches clients to examine thoughts, accept facts, and act on controllable behaviors. This pairing also underpins resilience: acceptance reduces futile rumination, and purposeful action rebuilds agency. Far from passive, acceptance frees bandwidth; it redirects attention from unchangeable conditions to skillful responses, where small wins accumulate into momentum.

Practices for Daily Use

To translate the maxim into habit, begin by drawing a quick three-column scan: cannot change, can influence, can control; then commit the next concrete step in the rightmost column. Before acting, breathe deliberately to steady your hands—box breathing or a slow exhale lengthens calm. Next, script an implementation intention: ‘If obstacle X appears, I will do Y’ (see Peter Gollwitzer, 1999). Close with a brief after-action review—what happened, what was learned, what to try next—so acceptance and improvement advance together. In this cadence, serenity and courage stop competing and start collaborating.