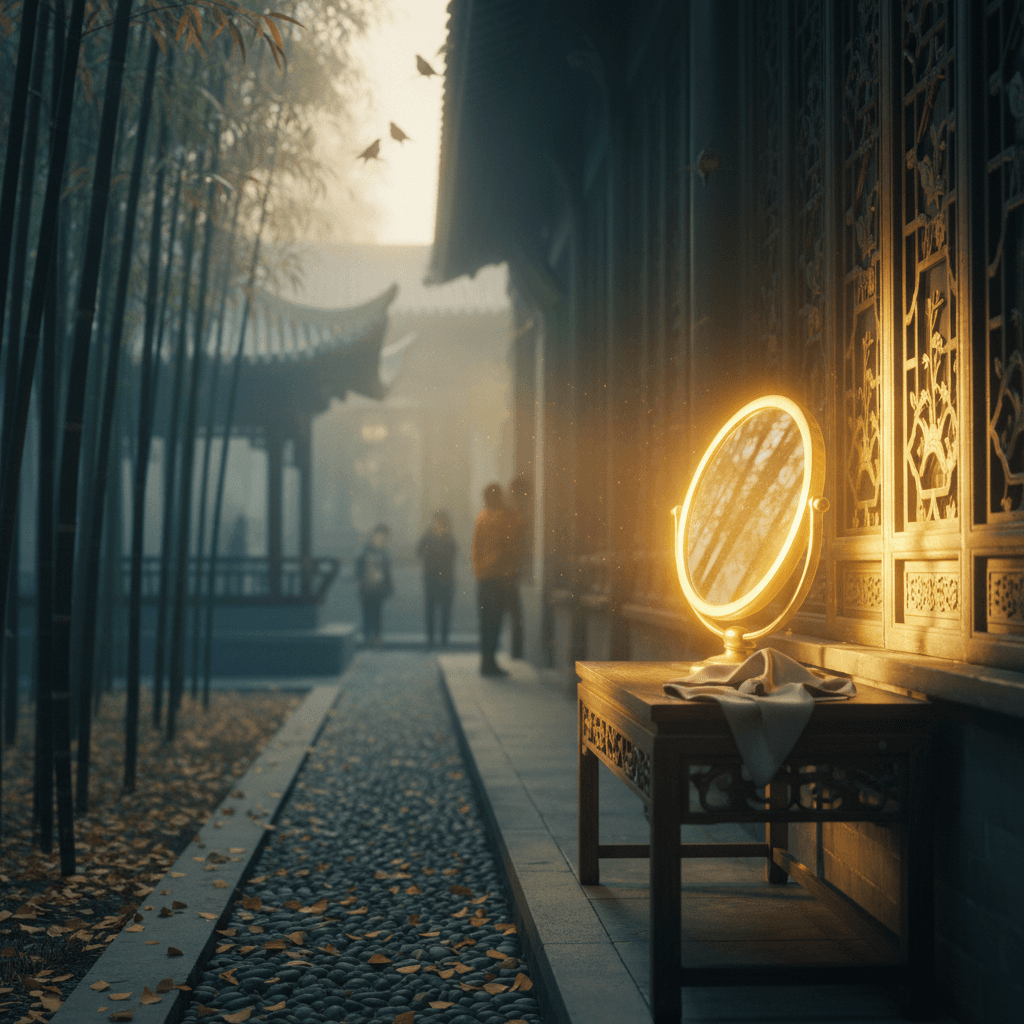

Polish Character Until It Illuminates Others

Polish your character until it shines; others will come to admire the light. — Confucius

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

What does this quote ask you to notice today?

Luminous Virtue and the Junzi Ideal

To begin, the line evokes a central Confucian conviction: character refined from within radiates outward as moral light. Confucius calls this inner power de—virtue as a kind of quiet magnetism—and holds up the junzi, the exemplary person, as its bearer. The Analects repeatedly suggests that genuine excellence attracts without clamoring; it is noticed because it is needed. In this sense, admiration is not a goal but a consequence of integrity. Rather than chasing acclaim, one cultivates clarity of heart and steadiness of conduct until they shine of their own accord.

The Craft of Polishing the Self

Building on this, Confucian texts favor a craft metaphor: character is shaped as jade is polished—patiently, layer by layer. The Analects likens the junzi’s qualities to jade’s warmth and luster, valued not for glitter but for depth. Polishing implies abrasion: feedback, discipline, and small corrections that cut away vanity. Thus the “shine” is not theatrical charisma; it is the sheen of reliability earned through consistent practice. In a world enamored of surfaces, Confucius invites us to prefer workmanship to spectacle, trusting that the well-made self will eventually be recognized.

Influence by Example, Not Assertion

Consequently, the path to admiration runs through example rather than advertising. Analects 2.1 compares rule by virtue to the North Star—steady in its place while others align around it. In the same spirit, Analects 4.25 states, “Virtue is not left to stand alone; he who practices it will have neighbors.” Confucian influence is thus transformative (ganhua): people gravitate toward constancy because it promises coherence. When one’s conduct is a fixed point, others calibrate their own. The light that draws them is guidance, not glare.

Daily Disciplines That Make Character Shine

In practice, Confucius prescribes rhythms that turn aspiration into habit. Learning (xue) grounds judgment; ritual (li) refines behavior into respect; reflection (si) converts experience into insight. Zengzi models this in Analects 1.4: “Each day I examine myself on three points,” a compact routine of scrutiny and repair. The Great Learning (Daxue, c. 3rd century BCE) echoes the same arc—“to make bright virtue shine forth”—by linking self-cultivation to order in family and state. Stepwise, the polish deepens; as alignment spreads from within, the light grows visible without.

Modern Leadership and the Quiet Magnet

Extending this insight, contemporary research on leadership echoes Confucius’s emphasis on inward foundations. Jim Collins’s Good to Great (2001) describes “Level 5 leaders” whose humility and fierce resolve attract followership without theatrics. Reputation in such accounts is a lagging indicator of character: trust accrues to those who choose substance over display. In workplaces and communities alike, the admired are often the quietly dependable—those whose decisions reveal a settled compass. Their light is credibility, and it draws because it steadies.

Adversity as the Final Polish

Ultimately, shine becomes evident under pressure. Mencius (4th c. BCE) observes that Heaven tempers those destined for great tasks through hardship, strengthening their sinews and testing their hearts. Friction, which would scuff a façade, refines genuine virtue, revealing depth where gloss would fade. Thus admiration arrives most surely when circumstances are darkest and character still holds. By welcoming trials as the wheel that smooths rough edges, we let integrity burn brighter—so that, without striving for an audience, others come to the light.