Rooted Lives Flourish: Martí’s Lesson on Belonging

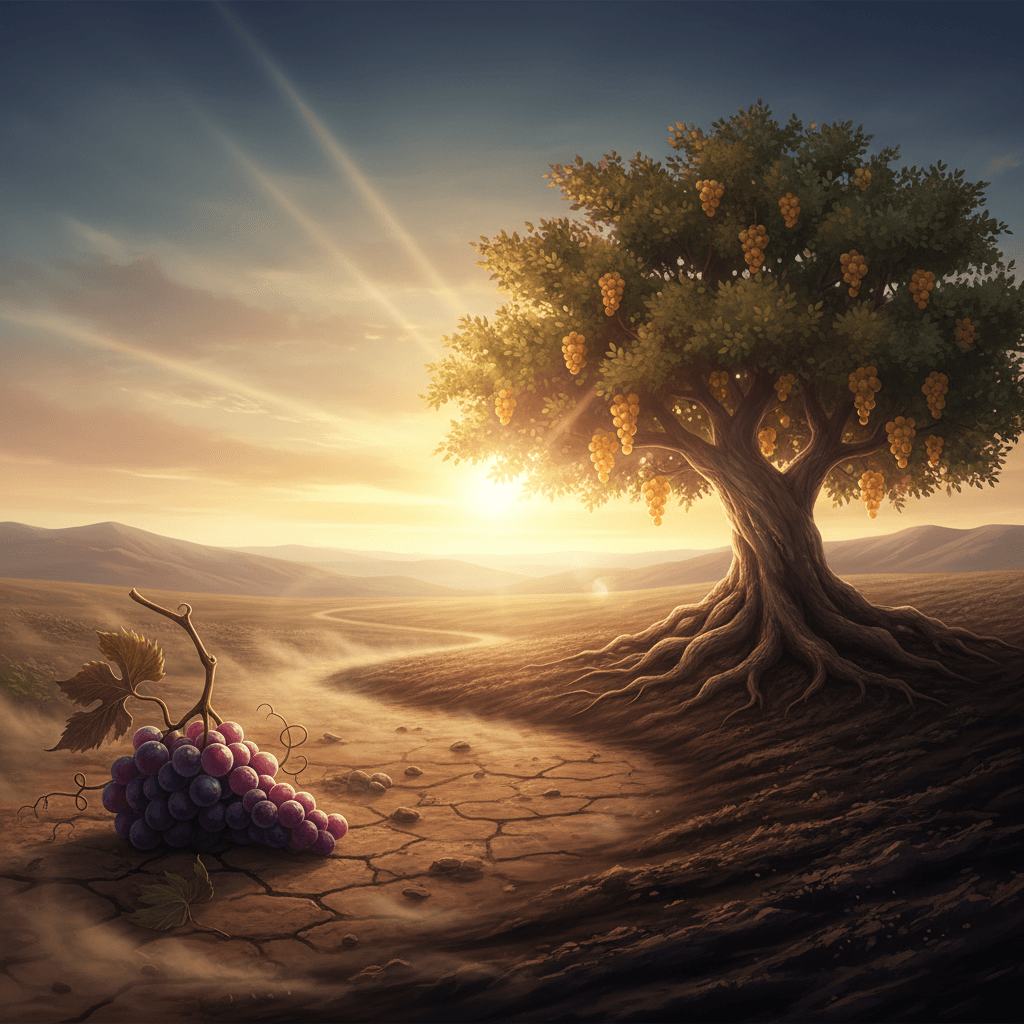

Men are like grapes, severed from the vine, they dry; the same men are like trees, rooted, they flourish. — José Martí

The Vine and the Tree: A Double Metaphor

Martí’s image moves deftly between vineyard and forest to reveal a single truth: life depends on connection. Grapes plucked from the vine become raisins, their sweetness intensified yet their vitality spent. Trees, by contrast, draw sustenance through roots that bind them to soil, symbionts, and seasons. In both cases, the channel of nourishment—whether a vine’s stem or a tree’s roots—decides the difference between drying out and blooming. Thus, the metaphor quietly shifts our gaze from individual grit to the networks that sustain it.

Martí in Exile: Roots Across the Sea

Building on that insight, Martí knew severance firsthand. He spent pivotal years in exile, organizing Cuba’s independence from abroad and speaking to migrant workers in Tampa and Key West to weave a far-flung community into a living cause. Rather than accept the loneliness of displacement, he cultivated new roots—newspapers, clubs, and letters—that carried sap to a shared future. In this way, the exile’s predicament becomes instructive: if separation dries us, deliberate rooting—through purpose and fellowship—restores flow.

Community as Lifeline: From Aristotle to Durkheim

From this personal lens, classical and sociological thought converge. Aristotle’s Politics argues humans are zoon politikon—beings fulfilled only in a polis, not in isolation. Centuries later, Émile Durkheim’s Suicide (1897) shows how social integration shields individuals from anomie, the withering brought by normlessness. The trajectory is clear: belonging is not a decorative extra; it is structural nourishment. Consequently, Martí’s vines and trees read as civic biology—our roots are obligations, rituals, and roles that tether us to meaning.

Modern Evidence: Social Capital and Health

Extending this idea, contemporary research measures how connection fosters flourishing. Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone (2000) charts the decline of social capital and the costs to trust, participation, and resilience. Meanwhile, a meta-analysis by Holt-Lunstad et al. (PLOS Medicine, 2010) links strong social relationships to markedly lower mortality risk, underscoring that ties protect both spirit and body. Even public health’s “social determinants” literature (Marmot, The Status Syndrome, 2004) confirms that embeddedness in stable networks predicts well-being. Roots, in short, are measurable.

Identity and Culture: "Nuestra América" and Self-Rooting

In this light, Martí’s essay Nuestra América (1891) adds a cultural grafting lesson: “Injértese en nuestras repúblicas el mundo; pero el tronco ha de ser el de nuestras repúblicas.” He welcomes borrowed knowledge as grafts, yet insists the trunk—the identity that feeds every branch—must be native. The point is not purity but priority: cultures flourish when external inputs fuse with internal roots. Thus the tree metaphor stretches from the personal to the national, where borrowed leaves cannot live without a living trunk.

Practical Roots: Habits That Keep Us Alive

Consequently, rooting is a practice, not a slogan. People who flourish tend to anchor themselves through repeating commitments: joining a local association, showing up for weekly rituals, mentoring and being mentored, learning the names of neighbors, and stewarding a place long enough to watch it change. These habits create the capillaries of a social root system—small but numerous channels that keep meaning circulating. Like a tree thickening rings, staying put long enough to bear and receive care turns time into nourishment.

Flourishing in Motion: Transplanting Without Withering

Finally, the metaphor does not condemn movement; it clarifies its terms. Gardeners know that transplanted trees survive when their roots are balled, watered, and set into welcoming soil. Likewise, migrants and career nomads thrive when they carry core commitments and quickly reattach—through language, service, worship, or craft guilds—into new communities. The lesson returns to Martí’s balance: if severed, we dry; if rooted, even after crossing oceans, we can leaf out again. Mobility becomes growth when connection travels with us.