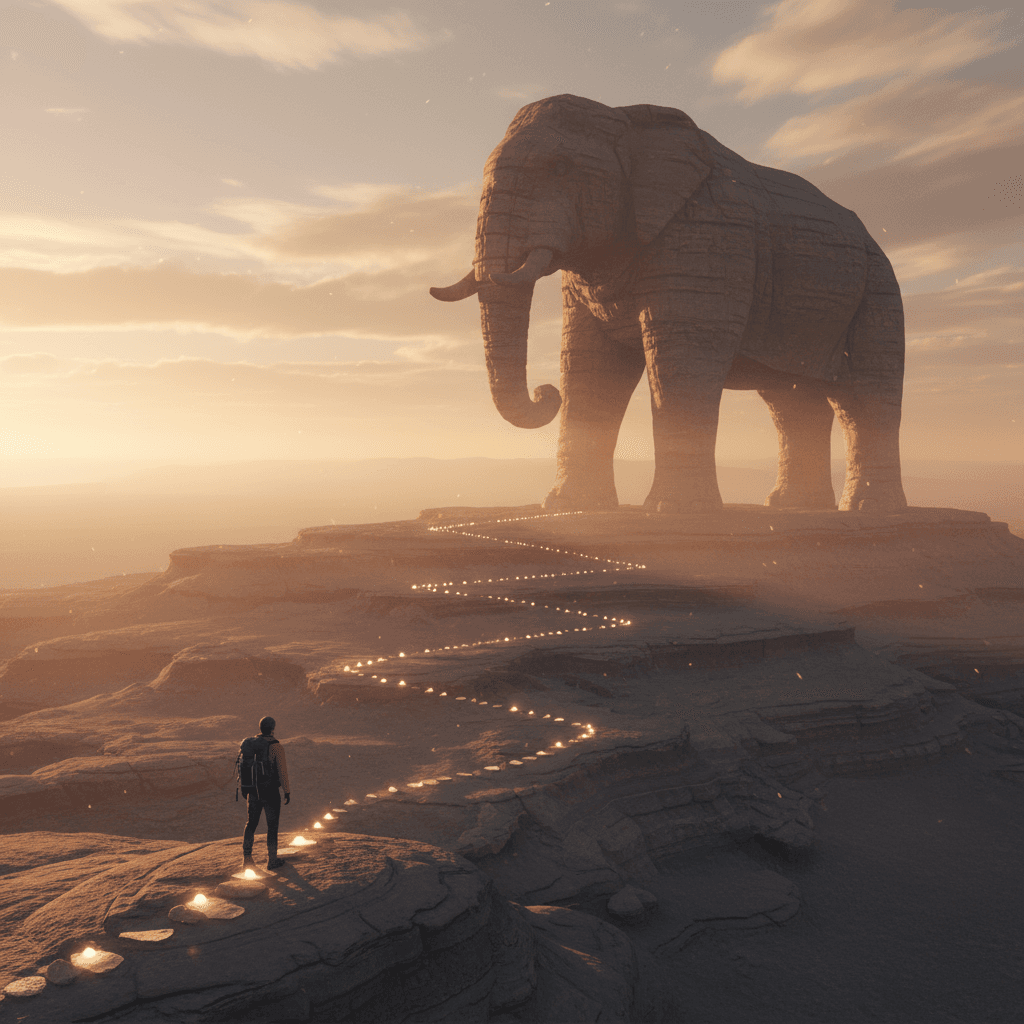

Tackling Giants, One Manageable Step at a Time

There is only one way to eat an elephant: a bite at a time. — Desmond Tutu

The Metaphor’s Simple Wisdom

At first glance, Tutu’s line makes you smile; then it offers a method. The “elephant” is any task so massive that it paralyzes us—healing a community, learning a craft, or rebuilding a life. By insisting on “a bite at a time,” he reframes enormity as a sequence of small, solvable actions. Moreover, the spirit of his anti-apartheid leadership reflects this pace of compassion: sustained pressure paired with daily acts of reconciliation. South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1996–2002) advanced not through a single grand gesture but hearing by hearing, testimony by testimony. The lesson is clear: when problems feel unwieldy, shrink the unit of effort until it becomes doable.

Why Small Bites Work Cognitively

Building on this, psychology explains the power of decomposition. Chunking helps the brain group complexity into manageable units, easing working-memory load. Even unfinished tasks create a productive tension—the Zeigarnik effect (1927) keeps intentions active until closed. Most compelling, Karl Weick’s “Small Wins” (1984) shows that modest, concrete victories can cascade into systemic change. Likewise, Teresa Amabile’s The Progress Principle (2011) documents how visible, daily progress fuels motivation and creativity. Each completed “bite” delivers feedback and dopamine, turning dread into momentum. In short, small steps are not mere tactics; they are neuropsychological levers.

From Vision to Plan: Breakdowns and Milestones

Translating insight into action requires structure. Start by clarifying outcomes, then craft a Work Breakdown Structure (PMI’s PMBOK tradition) that divides deliverables into tasks. Make those tasks SMART—Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound (Doran, 1981)—so each bite has crisp edges. Next, choose an execution cadence. Agile sprints (Agile Manifesto, 2001) time-box work into 1–2 week iterations with demos and retrospectives. Kanban limits work-in-progress so tasks actually finish. A personal example: outline a thesis by chapters, convert each into research and writing tasks, then schedule “sprints” of 90-minute sessions. By chaining these bites into milestones, the elephant becomes a calendar of small wins.

Historical Proofs of Incremental Triumph

History echoes the pattern. Before Apollo 11, NASA climbed a ladder: Mercury proved human spaceflight (1961), Gemini mastered rendezvous and spacewalks (1965–66), and only then did Apollo land on the Moon (1969). Each mission was a bite that validated the next (see NASA mission timelines). Similarly, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (launched 1988) reduced cases by over 99% through repeated, door-to-door immunization campaigns. Rather than chasing a single decisive strike, it orchestrated millions of tiny actions—local surveillance, cold-chain fixes, and community trust-building—until the global picture changed. The moral is steady: durable victories are accretions of discrete steps.

Motivation by Design: Engineering Small Wins

To sustain effort, design your environment to reward completion. The Pomodoro Technique (Cirillo, late 1980s) turns time into 25-minute bites with built-in breaks, reducing resistance to starting. Checklists do similar work by externalizing memory and celebrating progress—see Atul Gawande’s The Checklist Manifesto (2009) for how simple lists save lives. Further, make progress visible: burn-down charts, streak trackers, and progress bars convert ambiguity into motivation. As Amabile notes, even small visible movement lifts morale. Thus, you don’t merely take bites—you plate them, count them, and savor the finish.

Navigating Setbacks Without Losing Momentum

Inevitably, some bites are too big or poorly chosen. When that happens, reduce scope instead of abandoning the meal: halve task size, lengthen the timebox, or prototype before committing. Continuous improvement, or kaizen (Masaaki Imai, 1986), treats errors as information, not indictment. Additionally, favor “two-way doors” (Jeff Bezos, 2015)—reversible decisions—so missteps are inexpensive. In reliability terms, maintain an “error budget” (Google SRE, 2016): allow for learning-related failures while protecting core commitments. By normalizing small, recoverable mistakes, you preserve cadence and keep chewing.

A Humane, Nonliteral Reading

Finally, Tutu’s wording is metaphorical, not prescriptive. The point is compassion in the face of enormity—whether the task is personal healing or social repair. Grandstanding solutions often stall; small, faithful actions change reality. Therefore, when the problem looks impossible, return to the discipline of the next bite: define it, time-box it, finish it, and then choose the next. Progress, like reconciliation, moves one measured step at a time.