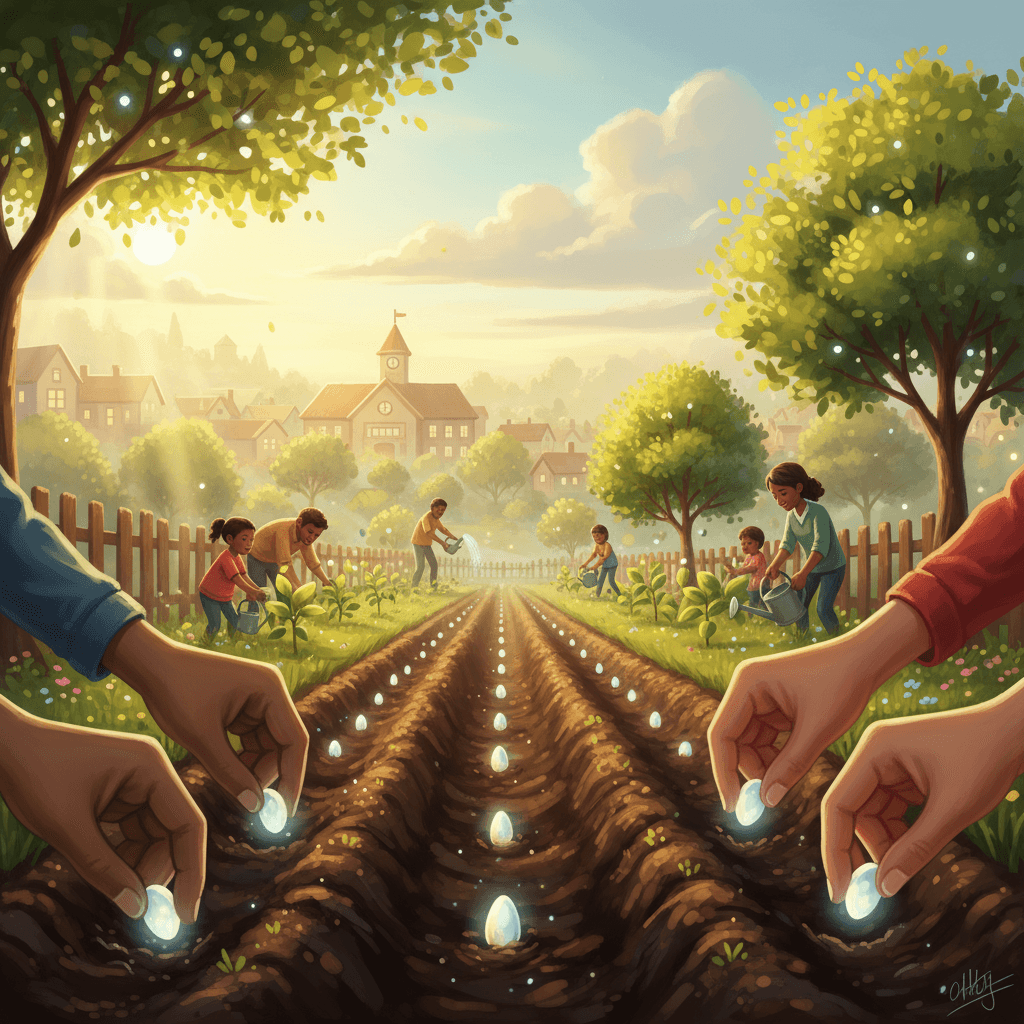

Cultivating Generous Ideas for Lasting Social Good

Sow generous ideas and tend them with effort to reap social good — Amartya Sen

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

What's one small action this suggests?

From Seed to Social Vision

At the outset, Sen’s exhortation frames ideas as seeds whose value depends on how inclusively they are conceived and how diligently they are nurtured. Generous ideas, in this sense, invite the perspectives of those most affected and refuse narrow definitions of welfare. They are expansive in empathy and rigorous in scope, asking not merely what grows quickly, but what nourishes many and endures. Sen’s public reasoning ideal—debate open to all—anchors this stance (The Idea of Justice, 2009).

The Capability Soil

Beneath that metaphor lies the capability approach: social good is harvested when people gain the real freedoms to lead lives they have reason to value (Development as Freedom, 1999). Generosity, therefore, is not charity; it is the design of conditions—health, education, voice—in which human capabilities can take root. Once planted in this soil, ideas become practical when they expand choices, especially for those historically constrained.

Cultivation Through Public Reason

From there, cultivation requires institutions that keep ideas oxygenated: free media, participatory forums, and accountable governments. Sen’s classic finding—that famines do not occur in functioning democracies with a free press—illustrates how scrutiny and feedback prevent catastrophic failure (Poverty and Famines, 1981). Deliberation is not a luxury; it is irrigation. By testing proposals in public and adjusting to criticism, societies convert aspiration into workable policy.

Watering With Evidence and Learning

Moreover, tending ideas means disciplined empiricism: measure, pilot, iterate. The Human Development Reports (since 1990), influenced by Sen and Mahbub ul Haq, reframed progress beyond GDP, guiding resources toward health and schooling. In parallel, field experiments and mixed-methods studies—popularized by Banerjee and Duflo’s Poor Economics (2011)—show how small design tweaks change outcomes. When evidence flows back into debate, ideas neither ossify nor drift; they learn.

Weeding Interests and Implementation Gaps

Even so, gardens invite weeds—capture, cynicism, and coordination failures. Here, institutional vigilance matters: transparency portals, social audits, and grievance redressal uproot distortions before they choke reform. India’s social audits of public works programs, for example, converted citizen oversight into tangible corrections (Drèze and Sen, An Uncertain Glory, 2013). By acknowledging incentives and power, we preserve generosity from becoming naïveté.

Harvests That Expand Freedom

Consequently, when care is sustained, harvests appear as capabilities realized. Kerala’s long investment in literacy and primary health produced low infant mortality at modest incomes (Drèze and Sen, Hunger and Public Action, 1989). Brazil’s participatory budgeting linked citizen priorities to health spending, contributing to reductions in infant mortality (Touchton and Wampler, Comparative Political Studies, 2014). These gains are not accidents; they are the yield of ideas that were inclusive at conception and persistent in care.

Seasons, Patience, and Polycentric Care

Ultimately, sowing once is not enough; seasons change, and stewardship must be shared. Polycentric arrangements—multiple, overlapping centers of problem-solving—build resilience, as Elinor Ostrom showed in Governing the Commons (1990). Through patient iteration and distributed responsibility, generous ideas survive droughts of attention and storms of politics. In this way, effort transforms vision into durable freedoms, and the garden keeps feeding the future.