From Setback to Sketch: Designing Bolder Futures

Turn setbacks into sketches for a bolder design — Frida Kahlo

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

What does this quote ask you to notice today?

From Wounds to Work

To begin, Frida Kahlo’s life embodies the maxim that adversity can be drafted into artistry. After a catastrophic bus accident in 1925, she was immobilized and in constant pain; yet a mirror mounted above her bed and a makeshift easel turned convalescence into a studio. Her early self-portraits—such as Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress (1926)—translated physical trauma into visual inquiry, transforming limitation into line and color (Herrera, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo, 1983). In this way, the setback became a sketch—an exploratory mark that didn’t deny suffering but redirected it toward form.

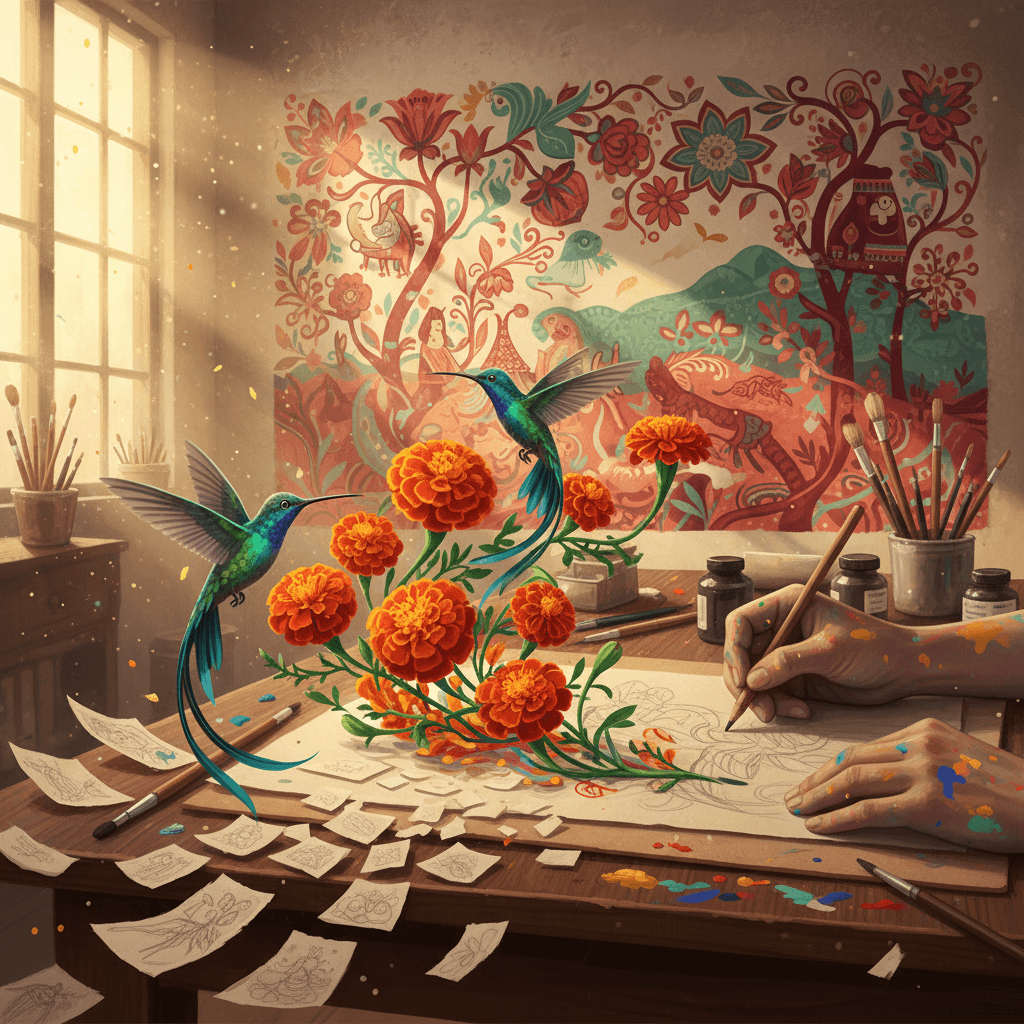

Lines on Plaster: The Sketch Habit

Building on this, Kahlo treated every surface as a draft of resilience. The Diary of Frida Kahlo (1995) shows pages where doodles, notes, and color studies morph into motifs later realized on canvas. Even her medical corsets became canvases—painted with symbols and flora—so that instruments of constraint turned into declarations of agency (V&A, Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, 2018). In effect, sketching wasn’t merely preparatory; it was a survival method, a way to process pain in increments until an image—and a stance—took shape.

Prototypes of Courage in Design Thinking

In parallel, contemporary design offers a practical echo: prototypes are sketches that metabolize failure into learning. IDEO’s mantra to “fail early to succeed sooner” reframes missteps as data rather than defeat (attributed to David Kelley, IDEO). Tim Brown’s Change by Design (2009) urges teams to “build to think,” treating rough models as cognitive tools. Like Kahlo’s studies and altered supports, these prototypes invite feedback, expose hidden assumptions, and convert setbacks into structured iteration that accelerates bold, human-centered solutions.

The Beauty of Repair

Similarly, kintsugi—the Japanese art of mending broken ceramics with lacquer and gold—makes fractures visible and valuable. Rather than disguising damage, it elevates it, suggesting that repair can enrich an object’s identity (Christy Bartlett, Flickwerk: The Aesthetics of Mended Japanese Ceramics, 2008). Kahlo’s oeuvre often follows this ethos: The Two Fridas (1939) stages exposed hearts and arteries as narrative lines, while The Broken Column (1944) renders medical supports with luminous severity. The break, acknowledged and traced, becomes the gilded seam that reorganizes design and meaning.

Turning Pain into Process

In practical terms, converting setbacks into sketches benefits from a deliberate loop. Start by naming the failure clearly, then render it as a visual brief—diagrams, storyboards, or thumbnail studies that capture constraints without judgment. Next, test a minimal prototype to externalize the idea and invite critique, echoing Kolb’s experiential learning cycle of concrete experience, reflection, abstraction, and experimentation (Kolb, 1984). Finally, run a brief retrospective to extract principles, as in agile practice (Derby & Larsen, Agile Retrospectives, 2006). Thus, emotion becomes information, and information becomes form.

Boldness as Responsibility

Ultimately, “bolder design” is not just louder aesthetics; it is a moral clarity about what scars can teach. Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) confronts gender norms, while works like Henry Ford Hospital (1932) give unflinching form to reproductive loss. By braiding identity, politics, and embodiment, she shows that boldness means rendering the hidden visible—so others can navigate it, too. In that spirit, every sketch born of a setback marks a route forward, guiding creators from private fracture to public meaning.