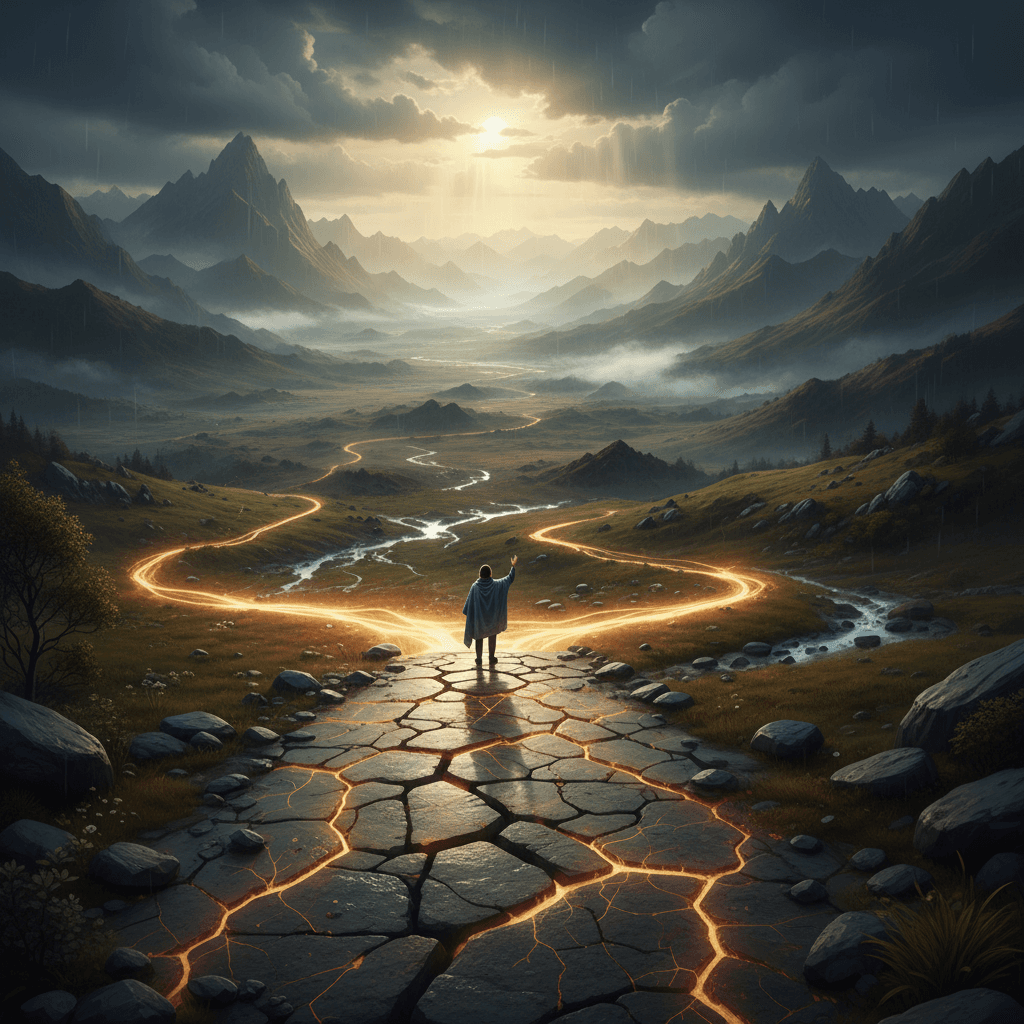

Turning Setbacks into Maps for New Routes

Turn setbacks into maps that point to new routes. — Haruki Murakami

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Where does this idea show up in your life right now?

Reframing Failure as Navigation

Murakami’s directive invites a subtle shift: treat every setback not as a barricade but as a signpost. In this view, adversity doesn’t merely halt progress; it reveals the contours of the terrain—where the ground is unstable, where the path bends, and where a previously unseen trail may begin. When read this way, disappointment becomes data. Rather than asking “Why did this happen to me?” we ask “What did this teach me about the landscape?” That reorientation preserves momentum and restores agency.

The Cartographer’s Mindset

Extending the metaphor, consider how navigators built better charts from hazards encountered at sea. Matthew Fontaine Maury compiled ship logs of winds and currents to create more accurate ocean charts (The Physical Geography of the Sea, 1855), turning scattered misadventures into collective guidance. Likewise, our personal logs—notes on what failed, where, and why—can be stitched into a usable map. Each misstep pins a coordinate: a constraint here, an underestimated variable there. Over time, the atlas grows, converting isolated errors into reliable routes.

Psychology of Rerouting

Psychology clarifies how to make this conversion. Carol Dweck’s work on growth mindset (Mindset, 2006) shows that viewing abilities as developable motivates learners to mine failure for feedback. Meanwhile, cognitive reappraisal reframes events to reduce threat and increase learning (James Gross, 1998), helping us interpret setbacks as informative rather than defining. To operationalize this shift, Peter Gollwitzer’s implementation intentions—if-then plans—link known pitfalls to specific responses (1999): “If deadline slippage occurs, then we pare scope and ship a minimal version.” Thus, emotion cools, action warms, and the map gains contour.

Murakami’s Lessons in Endurance

Murakami’s own practice exemplifies steady rerouting. In What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (2007), he writes, “Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional,” distilling a runner’s compact with discomfort. Training logs mirror navigational charts: pace, weather, fatigue—each entry recalibrates the next run. When injuries or plateaus arise, he alters cadence and course rather than quitting the road. The throughline is persistence with adaptation, a disciplined willingness to redraw the path while keeping the destination in view.

From Postmortem to Blueprint

Having sketched the mindset, the method follows. Begin with a brief after-action review: What did we intend, what happened, why, and what will we change next time? Next, name constraints explicitly and translate them into design requirements. Then, run small experiments that test one variable at a time. To preempt repeat errors, use a premortem—imagine the project has failed and list reasons (Gary Klein, 2007)—and convert those reasons into safeguards. Finally, codify lessons in a simple checklist (Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto, 2009) so the new route becomes repeatable.

Proof from Real-World Detours

History corroborates the promise of mapped setbacks. James Dyson reportedly built 5,127 prototypes before his bagless vacuum succeeded, turning each failure into a clearer engineering path (Dyson Ltd., company accounts). Similarly, Slack emerged from the internal messaging tool of a game studio whose MMO, Glitch, never found traction; the team pivoted in 2013, charting a new route from what went wrong in the original product. In both cases, the dead end became a junction—because its lessons were recorded, distilled, and then followed to a better road.