Where Control Ends, High Performance Begins

Created at: October 6, 2025

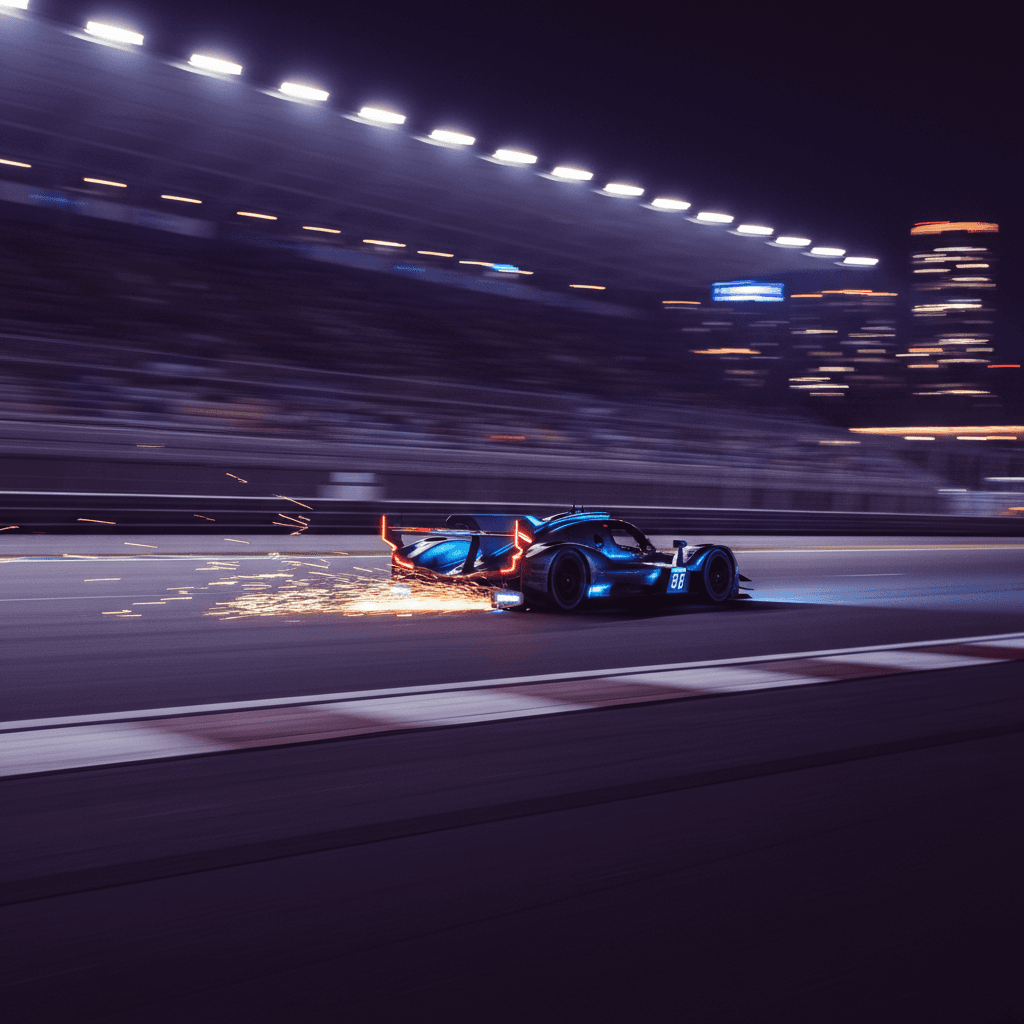

If everything seems under control, you're just not going fast enough. — Mario Andretti

Racing Wisdom at the Limit

Mario Andretti spoke from a cockpit where victory lives at the knife-edge of grip. In racing, the fastest lap often comes with the car dancing just past perfect composure—tires sliding a few degrees at their optimal slip angle, the chassis unsettled but purposeful. If everything feels serene, a driver is likely leaving speed on the table. That paradox captures the culture of elite motorsport: progress happens where feedback is sharp and mistakes, though costly, teach quickly. Extending this insight beyond the track, Andretti’s line spotlights a universal principle: comfort can mask untapped capacity. The sensation of “too much control” often means the system isn’t being asked to do enough.

The Productive Zone of Discomfort

Psychology echoes this logic. The Yerkes–Dodson law (1908) describes an inverted-U relationship between arousal and performance: too little stimulation breeds complacency; too much creates chaos; a charged middle ground unlocks peak output. Likewise, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow (1990) shows that we enter optimal focus when challenge slightly outstrips skill. Thus, if everything “seems under control,” we may be parked on the low, sleepy side of the curve. Carefully increasing pace nudges us into the stretch zone—unsettling enough to sharpen attention, yet bounded to avoid burnout.

Speed as a Catalyst for Innovation

Innovation tends to favor the swift. Joseph Schumpeter’s Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942) frames progress as “creative destruction,” where faster entrants displace the comfortable. In practice, companies institutionalize speed through rapid iteration: agile sprints, frequent releases, and fast feedback loops. Andy Grove’s Only the Paranoid Survive (1996) warns that hesitation at strategic inflection points is fatal, while Jeff Bezos’s shareholder letters emphasize a “bias for action” and reversible Type 2 decisions (2016). In this light, going “fast enough” doesn’t mean reckless acceleration; it means shortening the learning cycle so insight arrives before competitors—or circumstances—force it upon you.

Learning at the Edge, Without Falling Over

Operating near limits surfaces rich, timely information. Test pilots expand the flight envelope incrementally, collecting data at each step to validate assumptions before pushing further. Similarly, lean practices favor quick experiments and small batches, so errors are granular and reversible. The lesson is straightforward: speed should serve learning, not vanity. However, history also cautions that unmanaged haste can be tragic. High-stakes fields adopt “test like you fly” discipline and staged reviews to prevent compounding errors. The right pace feels taut but traceable, fast yet auditable.

Risk, Safety, and Intelligent Guardrails

Speed is sustainable only with strong guardrails. Motorsport evolved with head-and-neck restraints and energy-absorbing barriers, enabling drivers to explore limits more safely. Organizational analogs include pre-mortems, kill criteria, and red-team reviews; Weick and Sutcliffe’s Managing the Unexpected (2001) describes high-reliability practices that keep systems flexible under stress. Consequently, the aim is not maximum velocity but maximum validated velocity—fast enough to learn and lead, contained enough to survive and scale. Control shifts from preventing all surprises to absorbing them without catastrophe.

Practical Ways to Apply the Principle

Translate Andretti’s cue into habits: set stretch goals that require new methods; time-box work to force crisp decisions; ship 80% solutions and iterate; and run brief retrospectives to convert speed into learning. Anders Ericsson’s research on deliberate practice (1993) shows growth happens just beyond current ability, with immediate feedback. Begin modestly—shorten cycles, raise feedback frequency, and add safeguards as you accelerate. If the work feels a touch unstable but intelligible, you’re likely in the sweet spot where control gives way to progress.