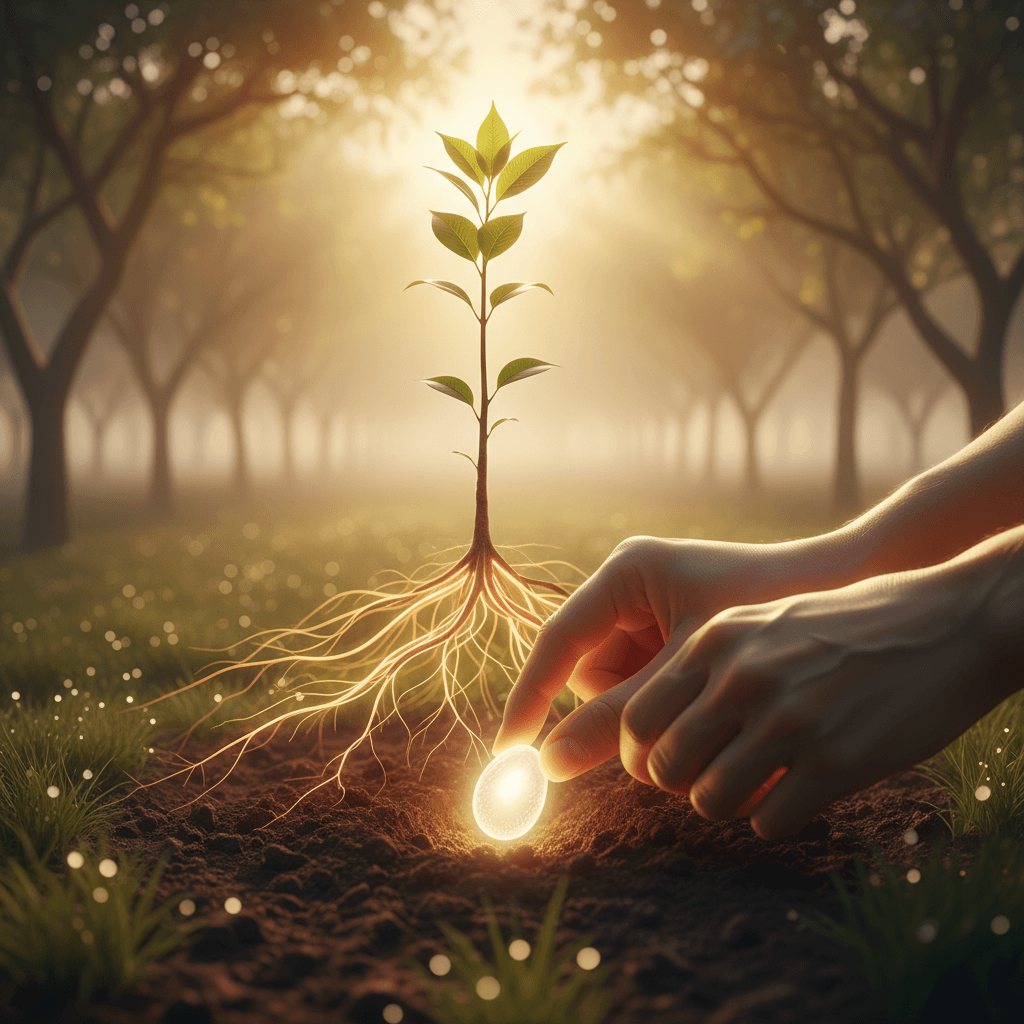

Nurturing Intentions Into Trees of Meaning

Plant intentions deep; tender them with deeds until they become trees of meaning. — Kahlil Gibran

Planting the Seed of Purpose

At the outset, the image of planting intentions deep urges us to bury our aims beneath the surface where roots can form away from distraction. Depth here means clarity: intentions anchored in values rather than impulse. Kahlil Gibran often married inner life to natural imagery, and in The Prophet (1923) he writes, “Work is love made visible,” suggesting that inward purpose seeks outward form. Thus, the seed is not a wish; it is a commitment incubated in quiet soil. By starting beneath the noise—journaling, reflection, and honest inventory—we give the seed protection and direction. Only then can it withstand weather when it emerges.

Watering Intentions with Concrete Deeds

From there, the metaphor insists that actions are the water and sun. Deeds metabolize intention into growth, turning abstract hope into embodied practice. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics II.1–4 shows that virtue is formed by habituation: we become just by doing just acts. Likewise, small, repeated deeds align the self with its declared purpose until the pattern becomes character. Even modern habit research echoes this cadence, documenting how tiny, consistent behaviors compound over time. In this light, tending is not sporadic zeal but rhythmic care—showing up before motivation arrives, keeping promises on unremarkable days, and letting the calendar become a trellis for the vine.

Time, Seasons, and Nonlinear Growth

In practice, trees do not rush; they thicken in rings invisible to our hurried glance. So too, intentions mature unevenly—quiet plateaus followed by sudden canopy. Anders Ericsson’s research on deliberate practice in Peak (2016) underscores this pattern: progress accrues through sustained attention, feedback, and rest, often bursting forth after long latency. Accepting seasonal rhythms protects us from uprooting what merely needs time. The gardener’s patience becomes strategic: we plan for droughts and frosts, mulching with routines that conserve energy. By honoring time’s slow arithmetic, we preserve the integrity of growth, trusting that the unseen work of roots precedes visible height.

Roots, Trunk, and the Emergence of Meaning

As seasons pass, meaning appears not as an ornament but as the living structure that deeds and days have built. Roots are our reasons—values and responsibilities—drawing nourishment from experience; the trunk is integrity, bearing the weight of consequence; branches are relationships and contributions that extend beyond the self. Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning (1946) shows how purpose emerges where responsibility meets freedom, even amid suffering. In this sense, meaning is not discovered fully formed; it is grown through chosen acts that align pain, talent, and service. The tree stands as a record of that alignment—every ring a remembered promise kept.

Pruning Failure into Future Growth

Moreover, tending requires pruning—cutting back to channel life into what matters. Setbacks, mistakes, and deadwood are not indictments but invitations. Carol Dweck’s Mindset (2006) documents how framing failure as information fosters resilience and ongoing effort. The gardener’s equivalent is selective loss for strategic gain: we remove misguided shoots, redirect sap, and let light reach stunted parts. Through reflection, feedback, and iteration, intentions regain vigor. Thus, failure becomes formative, not final; it strengthens the structure so that storms bend rather than break the canopy.

From a Single Tree to a Living Forest

Ultimately, a tree of meaning alters its environment—casting shade, holding soil, and offering fruit. Our cultivated intentions, once embodied, shape more than ourselves; they seed a commons. Elinor Ostrom’s Governing the Commons (1990) shows how communities can steward shared resources through norms, trust, and collective action. Likewise, personal integrity scales into social ecology: one steady life invites others to plant. As roots intertwine, the wind breaks, the soil deepens, and a forest emerges—proof that private tending can yield public good. In this way, the circle closes: intentions planted deep become habitats of meaning for many.