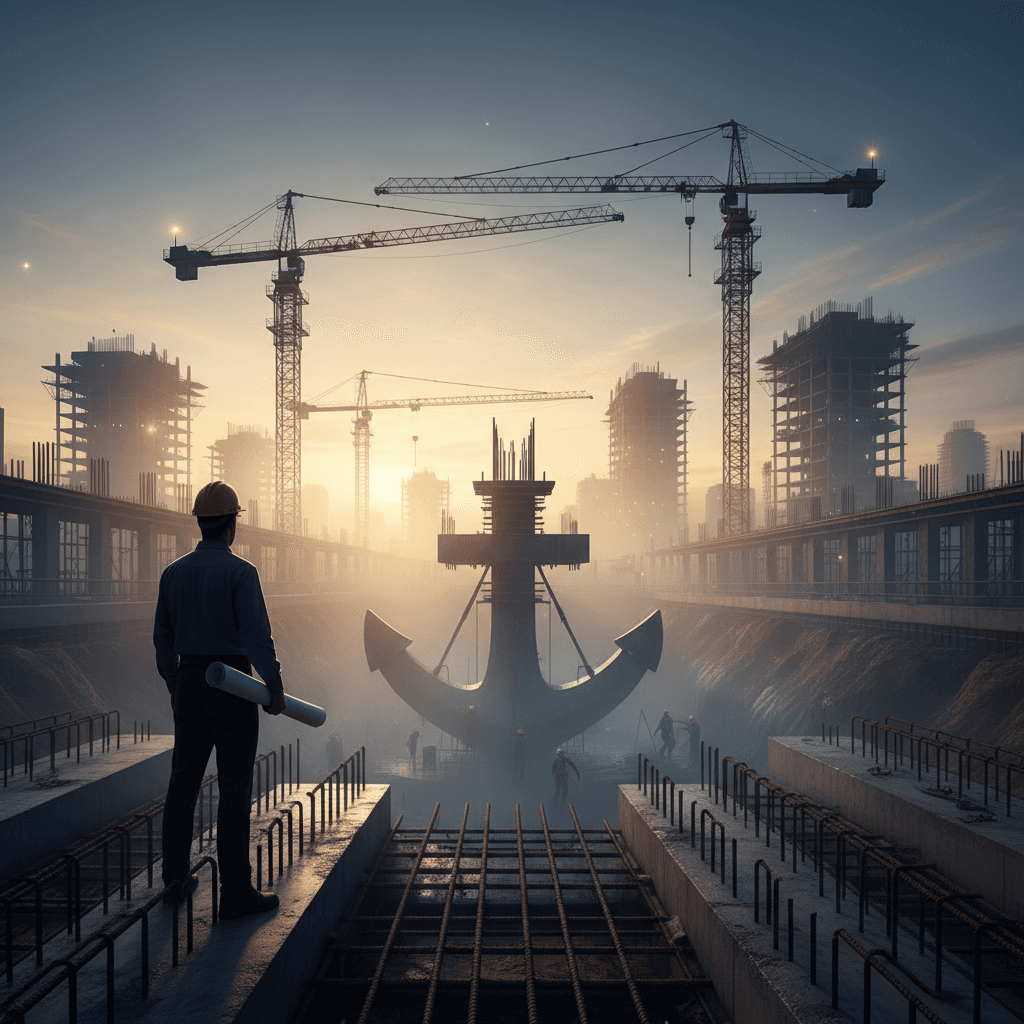

Anchoring Dreams in Work, Building Tomorrow

Dreams anchored in labor become the foundations of tomorrow. — W. E. B. Du Bois

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Why might this line matter today, not tomorrow?

Vision That Demands Sweat

Du Bois’s line binds aspiration to effort, insisting that hope without toil remains a vapor. Dreams, he implies, do not merely predict the future; they prepare it. When vision meets disciplined labor—study, organizing, institution-building—it pours concrete for the next generation’s footing. Thus, the future is not an accident but a construction site. From this starting point, his career reads like a proof-by-example, showing how rigorous work translates ideals into durable change.

The Color Line and the Work of Hope

To see how, we step into his era. After Reconstruction, Jim Crow hardened across the South while industrial cities swelled with Black migrants. In The Souls of Black Folk (1903), Du Bois named “the problem of the twentieth century” as the color line, and described the strain of “double consciousness.” Yet he treated these diagnoses as mandates for action. Through the Niagara Movement (1905) and the founding of the NAACP (1909), he positioned collective labor—not mere optimism—as the engine of rights. Thus, the dream of equality became a program: research, litigation, organizing, and public persuasion.

Data As Brick and Mortar

Crucially, Du Bois turned empirical study into civic infrastructure. The Philadelphia Negro (1899) mapped jobs, housing, and health with unprecedented rigor, while the Atlanta University Studies built year-over-year evidence on Black life. This was not data for its own sake; it was leverage. By measuring reality, he showed where to apply pressure and how to rebut myths that excused injustice. In this way, methodical inquiry became labor that fortified tomorrow’s policies—proof that knowledge, when anchored to action, lays foundations as surely as stone.

Institutions That Outlast Individuals

Building on research, Du Bois erected platforms that could carry the work forward. As editor of The Crisis (from 1910), he turned journalism into mobilization, translating analysis into campaigns and public will. He also promoted economic self-help through Economic Co-operation Among Negro Americans (1907), sketching cooperative models that could shield communities and compound gains. Moreover, the “Talented Tenth” essay (1903) argued for educating a leadership cadre able to seed schools, associations, and businesses. Institutions, he understood, are time machines: they ferry today’s labor into tomorrow’s opportunities.

Collective Labor and Democratic Reconstruction

Pushing further, Black Reconstruction in America (1935) reframed the nation’s rebirth after the Civil War as a democratic project driven by Black workers, including the “general strike” of the enslaved. This interpretation made labor—not benevolence—the decisive mover of freedom. Du Bois extended that logic globally through Pan-African Congresses (1919–1921), linking anticolonial dreams to organized action. In later years, he moved to Ghana (1961) to work on the Encyclopedia Africana, embodying his belief that scholarship and solidarity forge a shared future. Thus, the foundation widens when labor is collective and international.

From Du Bois to Practical Design

Consequently, the lesson travels well beyond his century. The NAACP’s legal victories, culminating in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), rested on decades of groundwork by organizations Du Bois helped launch. Today, the pattern holds: define the dream, translate it into projects, measure relentlessly, and build institutions that persist. Whether starting a cooperative, a lab, or a civic campaign, couple vision with schedules, partnerships, and feedback loops. In Du Bois’s terms, tomorrow is not granted; it is graded by our effort. When dreams are anchored in labor, they stop floating—and start bearing weight.