Dare to Be Odd, Design for Truth

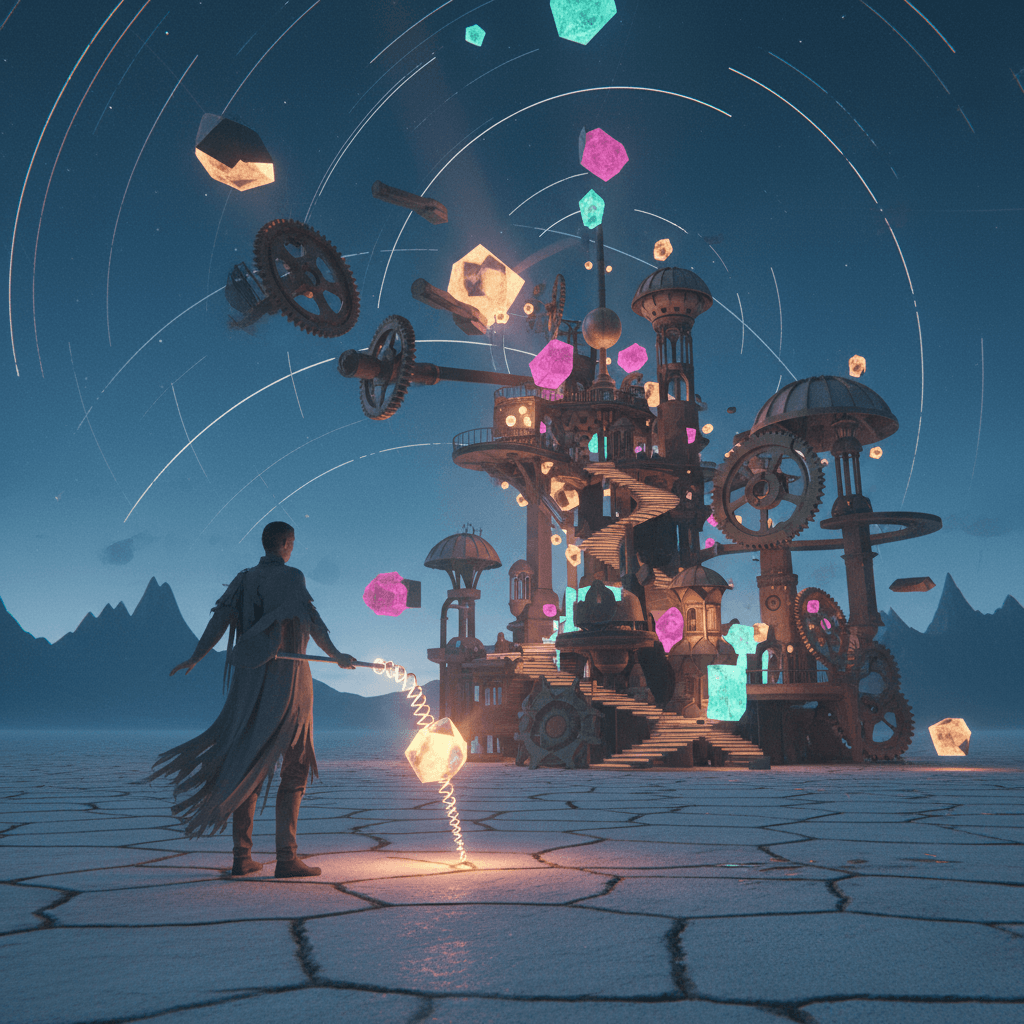

Dare to be odd, then build the world that honors your strange truth. — E. E. Cummings

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Where does this idea show up in your life right now?

A Manifesto of Creative Defiance

E. E. Cummings’ line fuses identity with architecture: first, dare to be odd; then, build a world that knows how to honor that oddness. His poetry—lowercase rebellions, inverted syntax, and unabashed feeling—models this stance. “anyone lived in a pretty how town” (1940) portrays individuals swept by conformist tides, yet quietly true to themselves; the form itself enacts freedom. Thus the quote is not mere self-help; it’s a civic imperative. It asks us to treat individuality as a design brief, transforming private authenticity into public structures. In that light, the “strange truth” isn’t a quirk to be polished away but a compass for building spaces, norms, and tools where difference is native rather than tolerated.

From Selfhood to Systems

To move from credo to craft, we translate oddness into system design. Inclusive design demonstrates how so-called edge cases reveal better defaults; Kat Holmes’s Mismatch (2018) shows that designing for difference often improves experiences for everyone. Consider curb cuts: created for wheelchair users, they now aid travelers with strollers and carts, proving that honoring a specific need can shape universal benefit. In the same spirit, organizations can define policies—flexible schedules, pronoun practices, multiple feedback modes—that normalize variance rather than punish it. By treating the unique as foundational, we convert private strangeness into public capability, setting the stage for broader cultural change in the sections that follow.

Echoes Across Literature and Thought

Historically, the call to oddness sounds alongside democratic humanism. Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself (1855) embraces multitudes, while Thoreau’s “different drummer” invites principled deviation. James Baldwin’s The Creative Process (1962) argues that the artist uncovers truths society resists—an echo of Cummings’ “strange truth.” Even Cummings’ “since feeling is first” (1926) privileges living over rigid rationalism, suggesting that form should bend to felt reality. These voices, taken together, insist that deviation is not error but discovery. Consequently, honoring difference becomes a method of knowledge-making: we learn what a culture values by how it treats what it deems odd, a theme that comes alive in real communities.

Communities that Make Space for Difference

In practice, world-building begins where people gather. Pride, whose roots trace to the 1969 Stonewall uprising, codified visibility into rituals, routes, and rights that honor queer lives. Burning Man’s principles (Larry Harvey, 2004) center “radical self-expression,” turning a temporary city into a laboratory for norms that welcome eccentricity. Open-source communities similarly affirm distinct voices through meritocratic contribution logs and transparent decision-making; version control itself renders difference visible and valuable. These cases prove that the right rules—clear participation paths, accountable leadership, and shared artifacts—can normalize the unusual. Yet even vibrant cultures need containers that protect dissent without calcifying it, a balance best explained by research on group dynamics.

Psychological Safety and Productive Dissent

Amy Edmondson’s studies (1999) show that psychological safety lets teams surface anomalies early, preventing errors and enabling innovation. Corporate lore echoes this: 3M’s discretionary time helped Art Fry and Spencer Silver evolve a failed adhesive into Post-it Notes in the 1970s; Pixar’s Braintrust sessions (Ed Catmull, Creativity, Inc., 2014) institutionalize candid critique while safeguarding creators. In each case, systems reward forthright oddities—half-ideas, outliers, inconvenient truths—so they can mature into breakthroughs. Therefore, honoring strangeness is not indulgence; it is operational excellence. With that rationale established, we can sketch a practical blueprint for individuals and groups seeking to build such worlds intentionally.

A Practical Blueprint for Your World

Begin small: write your “odd thesis”—a one-sentence statement of the truth you refuse to trade away. Next, convene allies and draft norms that protect it: how you meet, decide, disagree, and repair. Elinor Ostrom’s Governing the Commons (1990) shows that clear, local rules with fair enforcement sustain diverse communities. Then, prototype: a newsletter, pop-up event, or micro-product that embeds your norms in practice. Measure belonging with simple signals—retention, referrals, and anonymous check-ins—and iterate. Finally, scale slowly by teaching your rituals to newcomers so culture does not dilute under growth. As these habits take root, ethics must remain central, ensuring freedom does not become license.

The Ethics of Eccentric Freedom

To sustain a world that honors strangeness, tether liberty to care. John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty (1859) frames the harm principle: robust freedom up to the point of harm to others. Pair this with intellectual humility—Paul Saffo’s “strong opinions, weakly held” (2008)—so convictions adapt to evidence. Hospitality to difference, as Richard Kearney argues in Strangers, Gods and Monsters (2003), transforms fear into encounter. In practice, this means clear boundaries against harm, transparent accountability, and a standing invitation to revise norms when they exclude. Thus the circle completes: dare to be odd, then design a world where your oddness—and others’—can flourish without doing violence to the commons.