Choosing Hard Things: The Original Moonshot Mindset

We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard. — John F. Kennedy

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Where does this idea show up in your life right now?

A Creed of Constructive Difficulty

Kennedy’s line reframes hardship as a chosen catalyst rather than a deterrent. By declaring that the nation would pursue tasks precisely because they are hard, he cast difficulty as the forge of capability and character. This mirrors William James’s notion of the “strenuous mood” (1907), where voluntary exertion awakens latent energies. In this light, the quote is less bravado than a civic ethic: difficulty as a deliberate instrument for growth.

Cold War Context and Public Purpose

Placed within its moment, the vow answered a geopolitical challenge. After Yuri Gagarin’s 1961 orbital flight, Kennedy moved from urgency to vision—first with his pledge to Congress to land a man on the Moon “before this decade is out” (May 25, 1961), then with the Rice University speech (Sept 12, 1962) that etched the moral rationale. Thus, competition with the USSR became a public narrative of purpose, converting anxiety into coordinated national ambition.

Engineering the Near-Impossible

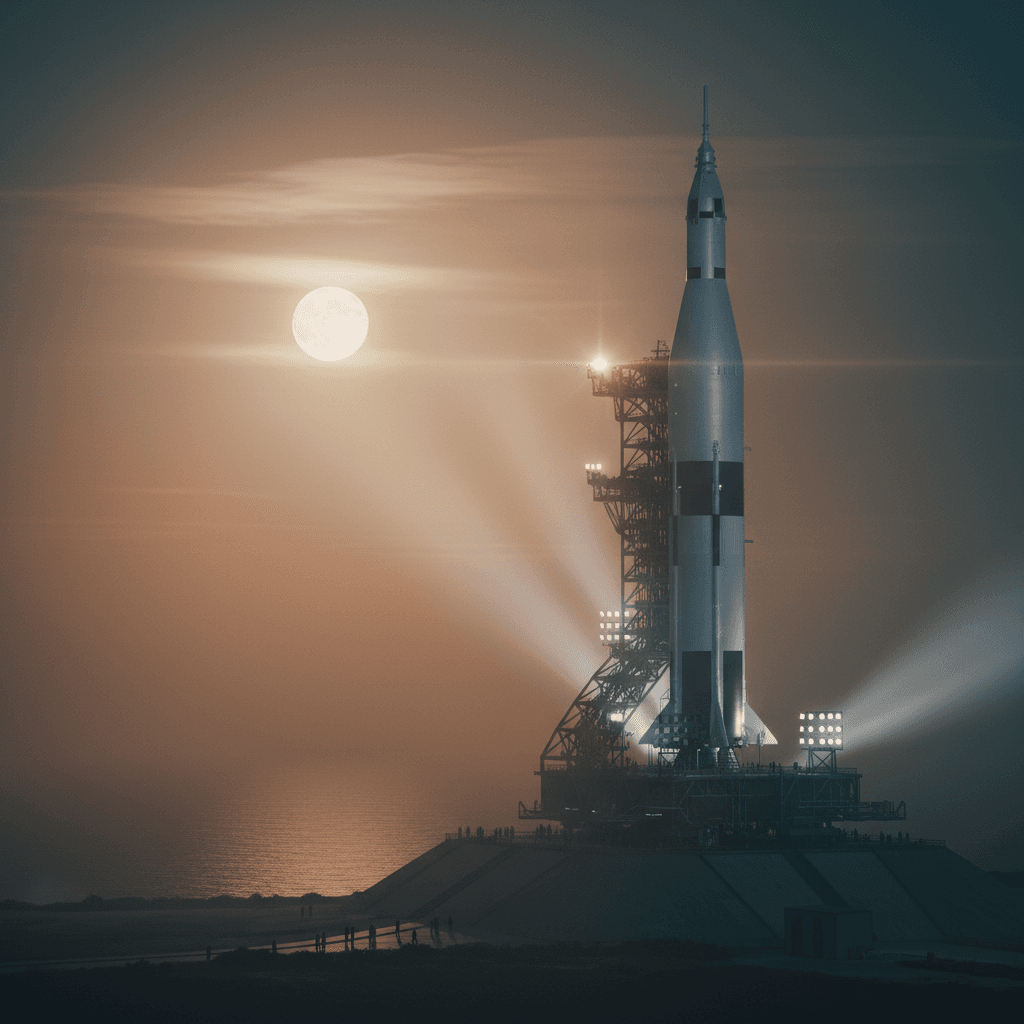

From there, rhetoric had to harden into hardware. The program adopted lunar-orbit rendezvous, championed by John C. Houbolt (1962), and built the Saturn V, a launch vehicle tall as a skyscraper. Equally audacious, the Apollo Guidance Computer ran on kilobytes of memory, yet—with Margaret Hamilton’s pioneering “software engineering”—executed real-time control (NASA History Series). In other words, the promise translated into systems thinking, iterative testing, and a culture that learned as fast as it built.

Risk, Accountability, and Public Consent

Yet hardship was not abstract; it was mortal. The Apollo 1 fire killed Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee (Jan 27, 1967), forcing redesigns and a reckoning with safety. Public support wavered, budgets tightened, and scrutiny intensified. Nevertheless, the program endured by institutionalizing lessons learned—transparent failure analysis, checklists, and redundancy—demonstrating that choosing the hard thing also means accepting accountability in full view of the citizenry.

The Moonshot as an Innovation Pattern

Consequently, “moonshot” became a template for tackling problems whose solutions demand coordination, deadlines, and measurable milestones. The Apollo model fused clear goals, empowered teams, rapid prototyping, and tolerance for bounded risk—principles echoed in DARPA programs (founded 1958) and later industrial R&D. This approach proved that ambition, when paired with disciplined execution, can compress timelines and convert improbable goals into cumulative, testable progress.

Legacy Beyond the Lunar Footprints

In the decades since Apollo 11 (July 20, 1969), the legacy has extended well past Tranquility Base. Systems engineering matured; integrated-circuit demand accelerated; remote sensing reshaped Earth science; and a generation of students chose STEM, inspired by televised launches and meticulous checklists. Thus, the payoff of choosing the hard path was not only a flag on the Moon but a durable capability to organize knowledge, industry, and imagination at scale.

Renewing the Ethic for Today’s Challenges

Ultimately, Kennedy’s cadence still offers a governing principle: aim where difficulty is highest and impact widest. Climate resilience, pandemic preparedness, fusion energy, and equitable AI each qualify as hard things worth choosing. By translating moral purpose into specific, time-bound goals—just as Rice Stadium’s speech did—societies can rekindle shared resolve and make tomorrow’s audacity feel, in retrospect, like today’s common sense.