From Solo to Chorus: Audre Lorde’s Charge

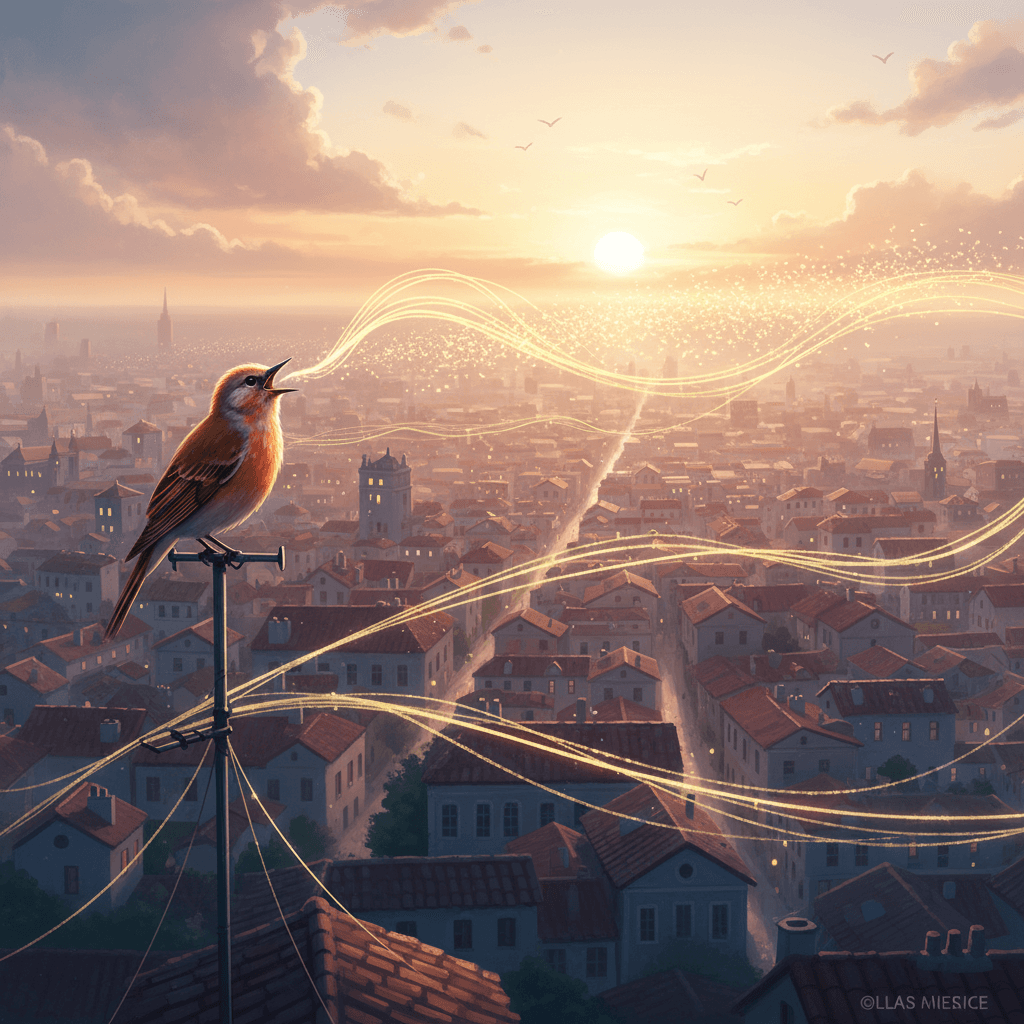

Sing your small brave song until the world learns the chorus. — Audre Lorde

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Why might this line matter today, not tomorrow?

The Seed of a Solo Voice

At the outset, Lorde’s line treats a single act of courage as a seed—small, yet genetically coded for abundance. A “small brave song” is personal truth articulated aloud, the moment silence gives way to utterance. This image echoes her insistence that voice is a political act; in “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action” (1977; in Sister Outsider, 1984), she argues that withholding speech does not keep us safe. Thus the solo is not a performance for applause but an offering, a way to test the air and invite resonance. Consequently, the goal is not mere expression but invitation: a melody simple and steady enough that others can learn it, then carry it farther than the first singer could alone.

Lorde’s Practice of Courage

Moving from metaphor to model, Lorde lived the practice she prescribed. In The Cancer Journals (1980), she transformed illness into testimony, refusing cosmetic silence and insisting on visibility as power. Likewise, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” (1977) frames creative utterance as a necessity for imagining freer futures. Her oft-cited warning—“Your silence will not protect you” (Sister Outsider, 1984)—was not scolding but solidarity: a recognition that speech carries risk and relief. By naming fear and speaking anyway, she showed how a fragile solo becomes durable through repetition. In that spirit, the invitation to sing small and brave is not about perfection, but presence—staying in key with one’s values even when the room seems unready.

How Choruses Form and Spread

From Lorde’s example, we can trace how solos turn communal. Social science describes this shift: people join when perceived support grows (Noelle-Neumann’s “spiral of silence,” 1974), when personal thresholds are crossed (Granovetter’s threshold models, 1978), and when shared emotion synchronizes a crowd (Durkheim’s “collective effervescence,” 1912). Persuasion research calls it social proof (Cialdini, 1984): each brave note lowers the cost of the next. Cultural practice matters too. In Black diasporic traditions, call-and-response trains communities to move from listening to answering; a leader’s line is structurally incomplete until the people reply. Consequently, the work of the soloist is to craft a phrase that travels—clear, repeatable, and rooted—so others can take it up and make it their own.

History’s Movements as Living Choirs

With this mechanism in view, history reads like a songbook. “We Shall Overcome” matured at Highlander Folk School and coursed through the U.S. civil rights movement as SNCC activists and voices like Fannie Lou Hamer carried it into jails and mass meetings. In South Africa, “Siyahamba” (“We are marching in the light of God”) became a luminous thread in anti-apartheid protests. Chile’s “El pueblo unido jamás será vencido” (Sergio Ortega/Quilapayún, 1973) turned plazas into choirs of defiance. Even the labor slogan “Bread and Roses,” linked to the 1912 Lawrence textile strike, fused dignity with demand. In each case, a small brave song traveled mouth to mouth until it belonged to many; the chorus did not dilute the message—it multiplied its reach.

Intersectionality as Harmony, Not Uniformity

Yet a chorus worth learning must hold many timbres. Lorde insisted that difference, honestly engaged, is generative; her critique in “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” (1979) warned against token inclusion. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s articulation of intersectionality (1989) clarifies why some voices are muted by overlapping oppressions—and why the arrangement must make room. Campaigns like “Say Her Name” (Crenshaw/AAPF, 2014) show how a chorus can correct its own omissions, amplifying Black women victims of state violence. Thus, harmony here is not sameness but skillful listening: adjusting volume, sharing the mic, and composing refrains that name what had been unnamed. The song grows truer as it broadens, because justice sounds like everyone accounted for.

Digital Hashtags as Contemporary Choruses

In the present, hashtags turn a lone refrain into a global round. #MeToo began with Tarana Burke’s 2006 grassroots work and swelled in 2017 as millions echoed the phrase, converting private harm into public reckoning. Black Lives Matter—founded by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi in 2013—scaled from posts to protests as the chant met the street. Online, repetition is infrastructure: retweets, duets, and stitches provide the rhythmic scaffolding that keeps time across continents. Still, the lesson remains Lorde’s: a chorus forms not from virality alone, but from voices grounded in lived truth. The more faithfully a small brave song reflects reality, the more readily the world learns—and keeps—its chorus.

Sustaining the Song: Care and Craft

Finally, every lasting chorus relies on breath. Organizers like Ella Baker modeled patient, local mentorship, reminding us that movements are ensembles, not solo tours. Contemporary wisdom on rest and community care—such as Tricia Hersey’s The Nap Ministry (2016; Rest Is Resistance, 2022)—frames restoration as part of strategy, not retreat. Craft matters too: refine the lyric, teach call-and-response, build song circles where newcomers learn the tune. Feedback becomes tuning, not silencing. In this way, courage becomes a practice: sing, listen, adjust, repeat. Over time, what began as one clear line turns customary; children hum it without knowing its origin, and the world—almost without noticing—has learned the chorus.