Shikamaru’s Wisdom: Effort, Friction, and Strategy

It’s not that I’m lazy. It’s just that everything is too troublesome. — Shikamaru, Naruto Series

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Why might this line matter today, not tomorrow?

Not Laziness, a Cost–Benefit Lens

At first glance, the line sounds like an excuse; yet Shikamaru reframes laziness as an assessment of friction. Calling things “too troublesome” functions as a quick cost–benefit signal: if the expected payoff is low and coordination or effort costs are high, abstaining can be rational. Linguistically, this resonates with the “principle of least effort,” where humans minimize energy for acceptable results (Zipf, 1949). Instead of moralizing inertia, the quote hints at a discriminating filter for action. By noticing drudgery’s hidden taxes—time fragmentation, context switching, and overhead—Shikamaru chooses when to engage. This reframing opens a door: perhaps the problem isn’t motivation, but poor task design that inflates hassle.

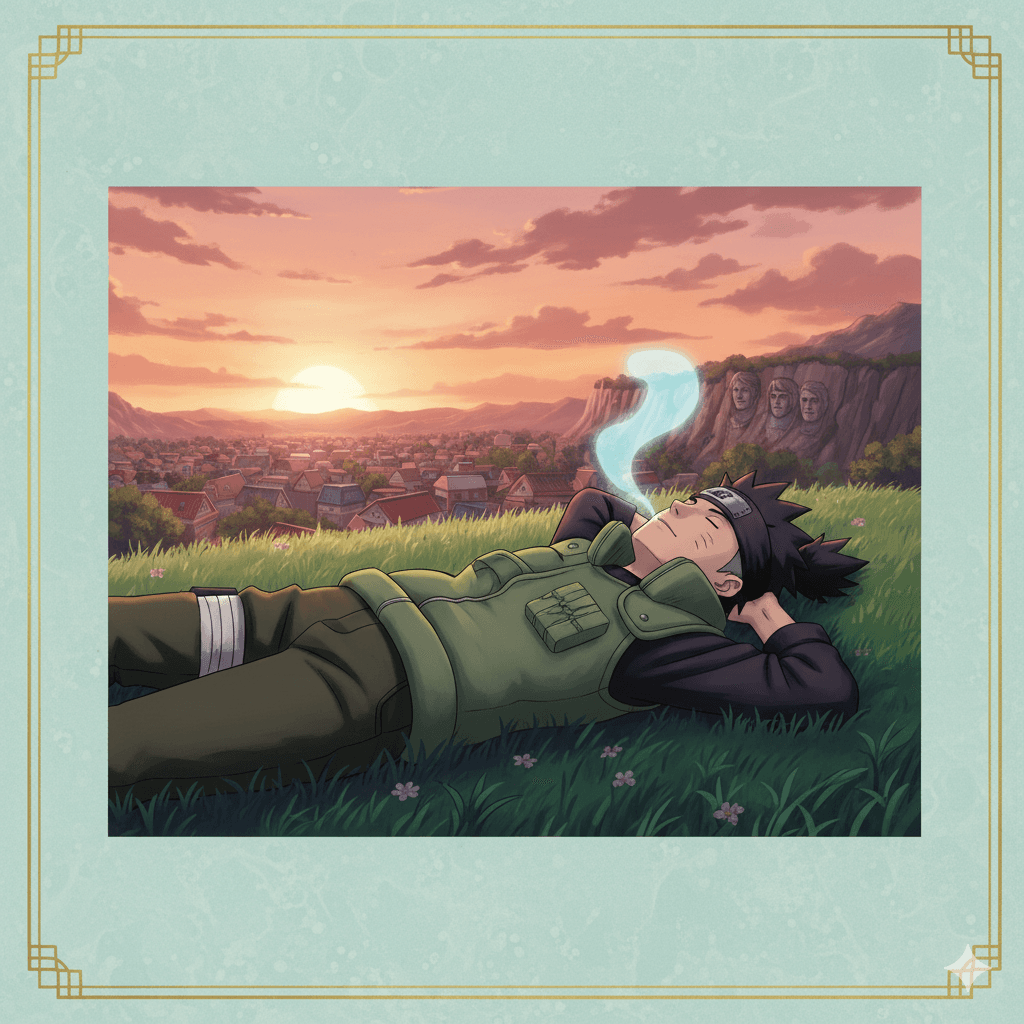

Mendokusai: Cultural Texture of Trouble

Moving from theory to context, Shikamaru’s refrain echoes the Japanese word mendokusai—“what a hassle,” a culturally common way to flag undue bother. In the Naruto series (2002 anime), his cloud-watching scenes and quiet sighs aren’t nihilistic; they’re expressions of a value hierarchy that prizes calm, simplicity, and well-timed effort. Rather than condemning drive, mendokusai highlights the social friction wrapped around tasks—interruptions, needless formality, and avoidable complexity. Framed this way, the catchphrase isn’t a shield against responsibility but a compass pointing to work that truly matters. Because when everything feels mendokusai, the issue may be the system, not the person.

Cognitive Friction and Decision Fatigue

Psychologically, “troublesome” often means high activation energy. The Fogg Behavior Model argues that behavior emerges when motivation, ability, and a prompt converge; raise friction and even strong motives falter (B.J. Fogg, 2009). Likewise, decision fatigue research suggests that repeated choices erode self-control, making low-friction defaults far more effective (Baumeister & Tierney, Willpower, 2011; Thaler & Sunstein, Nudge, 2008). Thus, Shikamaru’s aversion reads as a sensitivity to cognitive load. Reduce steps, clarify next actions, and automate where possible—and formerly “troublesome” tasks begin to look doable. In other words, redesign the runway and even a reluctant plane can take off.

Strategic Minimalism in the Chūnin Exams

Narratively, Shikamaru proves he’s no slacker. In the Chūnin Exam finals, he outmaneuvers Temari with shadows, fans, and timing, then calmly forfeits after achieving a checkmate-like position because his chakra reserves are spent (Naruto, Chūnin Exam arc, 2002 anime). Judges still promote him for exceptional judgment and strategic clarity. The lesson is subtle: he invests just enough effort to reveal leverage, then refuses gratuitous struggle. This is strategic minimalism—do the decisive thing, not everything. His “troublesome” filter screens out theatrics while preserving energy for battles that matter, turning apparent apathy into a disciplined economy of force.

From Apathy to Leadership: Reducing Future Trouble

Consequently, the character evolves from sighs to stewardship. After Asuma’s death, Shikamaru orchestrates a precise trap against Hidan—mapping terrain, baiting movements, and using wires and explosives to neutralize an immortal foe (Naruto Shippuden, Hidan and Kakuzu arc). He accepts near-term difficulty to shrink tomorrow’s chaos, mirroring shōgi: sacrifice now to simplify the endgame. The arc shows that recognizing hassle isn’t cowardice; it’s foresight. By tackling root causes rather than symptoms, he transforms “troublesome” into a mandate for smarter systems, proving that the best way to avoid nuisance is to design it out.

Applying the Lesson: Low-Friction, High-Leverage Habits

In practice, treat “too troublesome” as diagnostic data. First, shrink scope: define the smallest visible next action or apply the two-minute rule (David Allen, 2001). Second, lower friction: prepare tools in advance, bundle tasks, set defaults, and use checklists. Third, raise leverage: do the one task that dissolves five others. Finally, guard energy with time blocks and recovery. As these tweaks compound, motivation often “magically” appears—not from willpower, but from a smarter runway. In Shikamaru’s terms, when you make the smart move easier than the dumb one, even a self-professed slacker can lead with elegance.