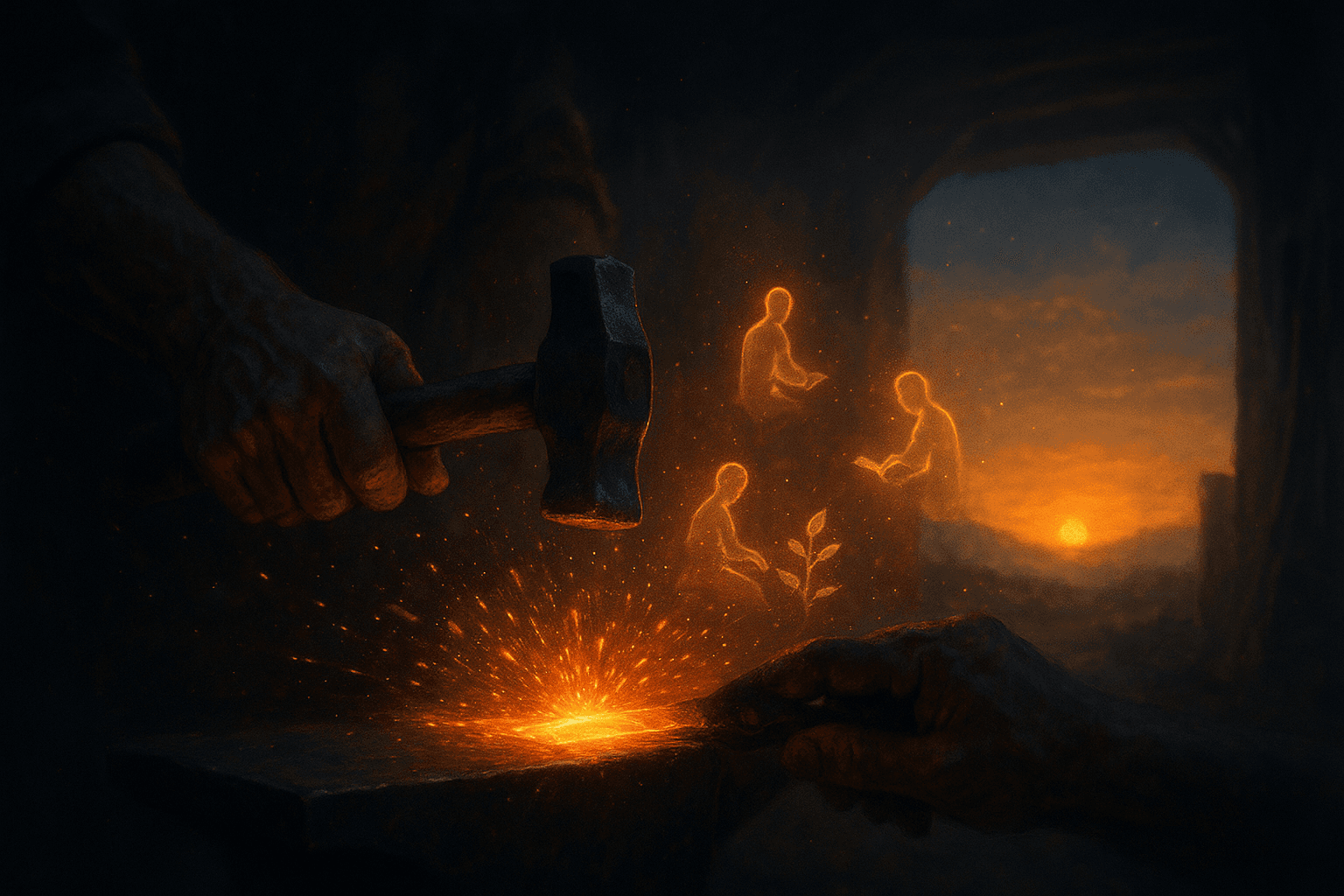

Forging Meaning from Life’s Raw Materials

Forge meaning from the raw materials of your life; the maker's hands transform circumstance. — Chinua Achebe

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Where does this idea show up in your life right now?

From Circumstance to Creation

Achebe’s line suggests that life does not arrive as a finished product but as unworked material. Experiences, whether joyful or harsh, are presented as raw ore rather than polished metal. Instead of accepting circumstance as fate, he proposes that meaning must be forged—actively shaped—by human effort. This shift from passive reception to creative engagement mirrors the way blacksmiths turn rough iron into tools: nothing useful appears without the fire of intention and the blows of repeated effort.

The Maker’s Hands as Human Agency

Moving deeper, the “maker’s hands” stand in for human agency, imagination, and responsibility. Achebe, whose novels like “Things Fall Apart” (1958) portray individuals struggling within powerful cultural and historical forces, insists that people are not merely victims of context. Rather, they are artisans of significance, capable of arranging memory, suffering, and hope into coherent patterns. In this sense, every choice—what to remember, what to forgive, what to resist—becomes part of the slow, deliberate craft of self-making.

Transformation Through Story and Interpretation

Achebe’s own career illustrates how transformation happens above all through stories. By retelling colonial history from an African perspective, he reworked inherited circumstances into a new narrative frame. Likewise, when individuals interpret their hardships as lessons instead of final verdicts, they reshape circumstances without changing the facts themselves. Viktor Frankl’s “Man’s Search for Meaning” (1946) echoes this idea: even in extreme suffering, the interpretation we forge becomes the decisive act of making meaning.

Craft, Discipline, and the Slow Work of Meaning

However, to ‘forge’ meaning implies heat, pressure, and time. Achebe’s metaphor rejects quick, ornamental positivity in favor of craft-like discipline. Just as a sculptor chips away stone, we refine our responses to setbacks, gradually revealing a form that was not obvious at the beginning. This process may involve revisiting painful memories, re-evaluating inherited beliefs, or patiently developing skills. Through repetition and revision—hallmarks of any maker’s practice—life’s chaos is slowly organized into a coherent design.

Shared Workshops: Community and Collective Making

Crucially, the maker in Achebe’s vision does not work alone. His novels show villages, families, and nations collectively shaping meaning through rituals, proverbs, and public memory. In the same way, people forge their lives within communities that provide tools: language, values, and traditions. Even resistance to those traditions is a kind of making that relies on them for contrast. Thus, meaning is not merely private inspiration; it is collaborative craftsmanship performed in the shared workshop of culture.

Living as an Ongoing Workbench

Finally, Achebe’s insight invites us to see each day as a workbench rather than a verdict. New experiences keep arriving as raw materials—some unwanted, others eagerly sought. The question becomes not “What has life done to me?” but “What can I fashion from what I have received?” By adopting the stance of the maker, we accept that our lives remain works in progress, continually hammered, reshaped, and refined into forms of meaning that might one day guide others in their own acts of transformation.