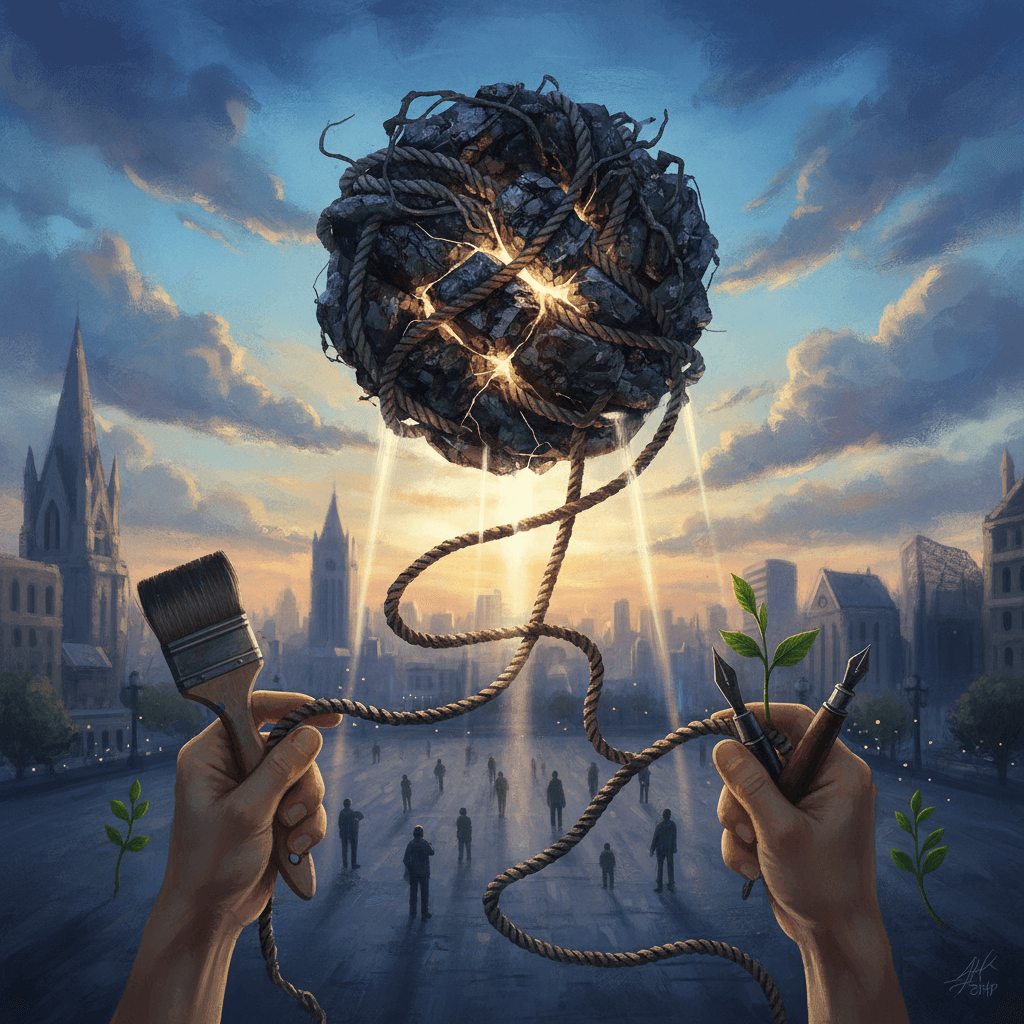

Unraveling Injustice with Steady, Imaginative Hands

Keep striking at the knot of injustice with steady, imaginative hands. — James Baldwin

—What lingers after this line?

One-minute reflection

Why might this line matter today, not tomorrow?

The Knot We Must Patiently Unravel

Baldwin’s metaphor invites us to picture injustice not as a single lock but as a tangled knot—interlaced threads of law, culture, economy, and memory. In The Fire Next Time (1963), he portrays racism as a web binding both oppressor and oppressed, warning that force alone cannot free us. The image resists the seductive legend of the Gordian knot, where Alexander simply cuts through (Arrian’s Anabasis, 2nd c. AD). Rather than a heroic slash, Baldwin urges repeated, skilled strikes that loosen strands without tearing the fabric of our shared life.

Steadiness as Organizing Craft

From this metaphor, we turn to method: steadiness. Movement victories rarely arrive by epiphany; they are crafted. Ella Baker’s quiet mentorship of SNCC (1960) embodied patient structure-building—“strong people don’t need strong leaders”—while Bayard Rustin’s logistical mastery produced the 1963 March on Washington’s disciplined chorus. Baldwin’s “A Talk to Teachers” (1963) likewise framed steadiness as moral endurance: facing reality daily and still showing up. Training, iteration, and follow-through keep hands steady on the knot, preventing the fray of panic and the fatigue of spectacle.

Imagination as a Tool of Liberation

Building on craft, imagination supplies the new angle of grip. In “The Creative Process” (1962), Baldwin claims the artist must disturb the peace so the truth can surface. That disturbance is also strategic: Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun (1959) and Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” (1964) re-scripted public feeling, widening the political aperture. Legal imagination worked similarly when Pauli Murray named “Jane Crow” and seeded arguments later echoed in Reed v. Reed (1971), while the NAACP LDF’s path to Brown v. Board of Education (1954) reframed equal protection itself. Imagination, then, is not ornament—it is leverage.

Tactics That Loosen the Tightest Loops

Continuing from vision to practice, the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–56) braided carpools, church networks, and litigation—Browder v. Gayle (1956)—to pry loose a specific strand of segregation. The 1963 March on Washington, choreographed by Rustin, paired moral theater with meticulous schedules, first aid, sanitation, and marshals. Research by Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan shows that nonviolent movements have historically succeeded about twice as often as violent ones (Why Civil Resistance Works, 2011). Such wins illustrate Baldwin’s counsel: persistent, well-aimed strikes loosen knots others called impossible.

Seeing Systems, Finding Leverage

To avoid hacking blindly, the work must map the knot. Donella Meadows’s “Leverage Points” (1999) reminds us that changing rules, information flows, and narratives can shift entire systems. Voter access reforms, fair housing enforcement, prosecutor accountability, and school funding formulas are not side quests—they are strands whose tension shapes the whole. Pairing data with story—budget analyses alongside testimonies like Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son (1955)—aligns feeling with fact. Thus, imagination identifies the leverage; steadiness applies pressure where change multiplies.

Many Hands, Shared Knots

Because no one hand can hold every strand, coalitions become the loom. The Memphis sanitation strike (1968) fused labor power, Black freedom claims, and faith-rooted discipline under the banner “I AM A MAN.” Fannie Lou Hamer’s moral clarity at the 1964 DNC expanded the constituency of conscience. Such convergences model how immigrant justice, disability rights, and environmental health movements interweave today. Trust-building, shared training, and mutual aid are not preliminaries—they are the braided rope that keeps our hands from slipping as the knot fights back.

Measuring Progress Without Losing Heart

Finally, endurance requires a way to count the unglamorous. Doug McAdam’s political process theory (1982) shows that movements win by aligning organization, strategy, and openings in power; many strikes fail early because they cannot outlast the calendar. Empirical work suggests that sustained participation by a small percentage of the populace can tip outcomes (Chenoweth, 2013). Baldwin’s No Name in the Street (1972) chronicles fatigue without surrender, reminding us that hope is practiced, not presumed. By setting proximate goals, marking incremental loosening, and returning tomorrow, we keep striking—steady, imaginative, and together.