Carving Meaning Through Daily Stoic Discipline

Disciplined choices carve a life of meaning from the raw material of each day. — Seneca

Stoic Roots of Daily Deliberation

Seneca’s line distills a Stoic conviction: meaning is not found but formed, choice by choice. In Letters to Lucilius and On the Shortness of Life (c. 49 CE), he argues that time is raw allotment; virtue is the artisan’s hand. Thus, the day is not a backdrop but a workshop. We do not wait for a meaningful life to appear—we shape it by selecting what to do, what to ignore, and how to endure. Carrying this forward, the Stoics treat intention as the hinge of character. A single action matters less than the settled habit of choosing well. Therefore, disciplined choices are not grim refusals; they are repeated affirmations of who one is becoming.

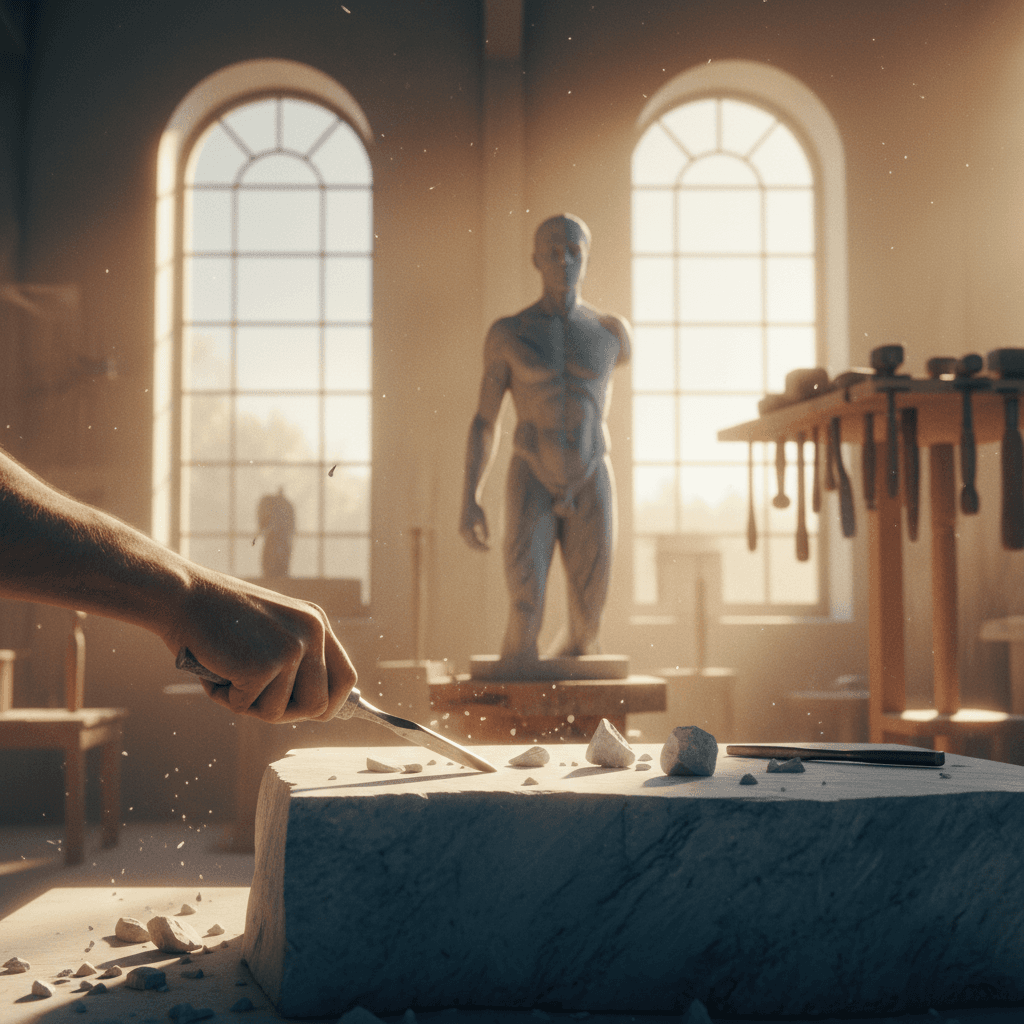

From Raw Material to Moral Craftsmanship

Seneca’s metaphor suggests the labor of a sculptor: the block is given; the statue is chosen. Epictetus calls this inner faculty prohairesis—the capacity to choose our stance (Discourses 1.1). We cannot command weather, markets, or other people, but we can shape our judgments, aims, and responses. Consequently, every inconvenience becomes workable material. A delay becomes patience practice; a success, a test of modesty; a setback, an anvil for resilience. In this craft view, discipline is creative: it chisels excess, reveals form, and leaves a coherent figure—character—where raw life once stood.

Habits That Make Discipline Easier

However, philosophy meets friction without tools. Modern research shows disciplined choices become sustainable when embedded in habits. Peter Gollwitzer’s work on implementation intentions (“If X, then I will Y,” 1999) turns vague resolve into automatic response. Wendy Wood’s findings (Good Habits, Bad Habits, 2019) show environment and repetition outperform sheer willpower. Accordingly, Stoic aims pair well with choice architecture: set a cue, precommit the action, reduce friction, and let the routine carry the virtue. Discipline then feels less like constant struggle and more like thoughtful design, harmonizing ancient counsel with contemporary evidence.

Guarding Time to Guard Meaning

Seneca warns that people are frugal with money yet lavish with hours, though time is the only nonrenewable asset (On the Shortness of Life). To carve meaning, one must first claim the marble—attention. In a noisy age, this implies boundaries, focused blocks, and deliberate recovery. In parallel, modern advocates of deep work note that sustained attention compounds results (Cal Newport, Deep Work, 2016). By deciding when to be available and for what, we ensure our best faculties meet our highest purposes. Discipline here is not denial; it is stewardship.

Review, Repent, and Re‑aim

To keep the chisel true, Seneca practiced evening self-examination, asking what he did, why, and how to improve (On Anger 3.36). This quiet audit converts experience into instruction. Marcus Aurelius models the same in Meditations—short notes that refine tomorrow by understanding today. With this rhythm, mistakes cease to be verdicts and become materials. Reflection yields forgiveness, forgiveness clears fear, and clarity resets direction. Thus, discipline stays humane and forward-looking: we close the day lighter, wiser, and ready to choose again.

Firmness Without Rigidity

Finally, Stoic discipline is not harsh asceticism. It prizes virtue while recognizing “preferred indifferents” like health or wealth as useful but not ultimate. This balanced stance allows firmness without brittleness: we aim steadily, yet adapt when reality shifts. Therefore, disciplined choices are guided by values and tempered by compassion—for others and ourselves. The outcome is not a narrow life but a coherent one, where daily decisions align effort with meaning, steadily revealing a well‑formed character in the grain of ordinary days.