Turning Longing into Artful Soulwork

Transform longing into art; the soul does its work through making. — Kahlil Gibran

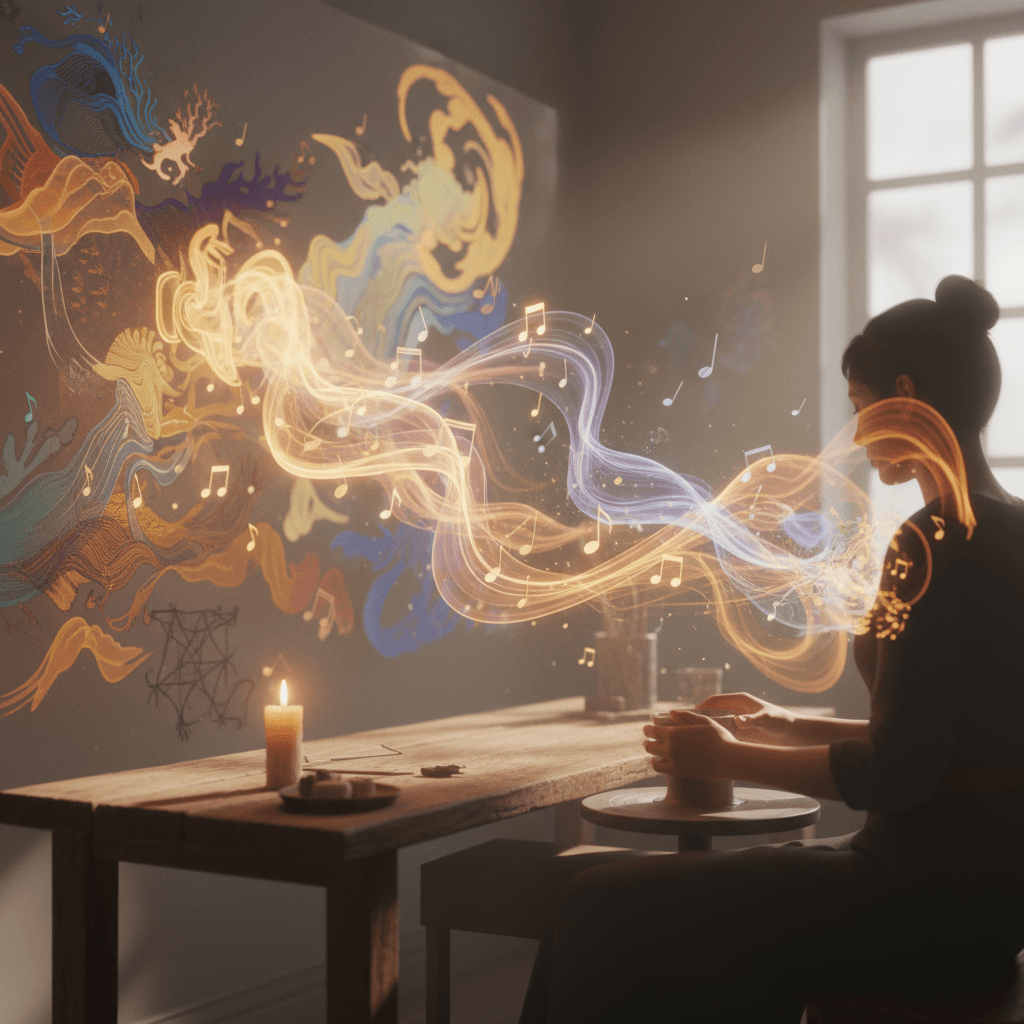

Longing as Creative Fuel

Gibran frames longing not as a deficit to be cured but as a force that can be transmuted. The ache for someone, somewhere, or some meaning becomes raw material—an emotional pigment waiting to be mixed into form. In this view, art is not an escape from desire but a way of giving desire a voice that can be held, seen, and shared. From there, the quote suggests a practical invitation: when you cannot resolve your yearning directly, you can still respond to it creatively. A diary entry becomes a poem; a sleepless night becomes a melody; a restless mind becomes a sketch. Longing doesn’t disappear, but it gains shape—and shape makes it livable.

Making as the Soul’s Labor

The second clause shifts the emphasis from emotion to agency: “the soul does its work through making.” Rather than presenting the soul as something purely contemplative, Gibran imagines it as industrious—working through the hands, breath, and attention of the maker. What is inward and wordless is translated into an outward artifact that can survive the moment. This is why the act of making often feels like more than productivity. As Aristotle notes in the *Nicomachean Ethics* (c. 340 BC), humans find fulfillment through purposeful activity; Gibran echoes that idea but relocates purpose in the soul’s deeper needs. Creation becomes a kind of inner vocation carried out in materials.

Art as Alchemy of Emotion

Because longing can be diffuse and painful, it often resists straightforward explanation. Art, however, excels at alchemy: it converts private sensation into shared symbol. A brushstroke can hold tenderness and grief at once; a short story can preserve a loss without reducing it to a lesson. In that conversion, the maker doesn’t deny the feeling—they refine it. This alchemy has long been recognized as a way to turn suffering into meaning. Viktor Frankl’s *Man’s Search for Meaning* (1946) argues that creating work can be one pathway to purpose amid pain; similarly, Gibran implies that longing becomes bearable when it is tasked with making something true, rather than merely consuming the heart.

From Private Ache to Shared Connection

Once longing is shaped into art, it can travel beyond the individual. The maker discovers that what felt isolating is often widely recognizable: another reader has wanted the same impossible thing, another listener has carried the same quiet hope. In this way, art becomes a bridge between solitary experience and communal understanding. Consider how Pablo Neruda’s *Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair* (1924) turns intensely personal desire into lines that countless strangers claim as their own. Gibran’s insight aligns with that tradition: the soul’s work is not only self-expression, but also the creation of meeting points where one person’s longing can resonate in another’s life.

The Discipline of Transmutation

Yet transforming longing into art is not merely catharsis; it is discipline. Feelings arrive uninvited, but making requires choice—returning to the page, revising a stanza, practicing a passage until it says what it needs to say. Through that effort, longing is no longer a passive condition; it becomes an active craft. This is where the quote subtly promises agency. Even when longing cannot be satisfied, it can be stewarded. The soul “does its work” through the repeated, sometimes humble acts of shaping—draft by draft, note by note—until the original ache has become something coherent, and coherence itself becomes a kind of consolation.

Creating Without Erasing the Desire

Finally, Gibran does not claim that art eliminates longing; instead, it dignifies it. The longing may remain, but it is no longer only a wound—it is also a source, a teacher, and a compass. Making does not replace life; it helps the maker live more honestly inside life’s unanswered questions. In that concluding sense, the quote offers a gentle ethic: treat your yearning as meaningful enough to be made into something. When the soul works through making, it turns what hurts into what helps—if not by granting closure, then by granting form, and with form, a steadier way to carry what you feel.